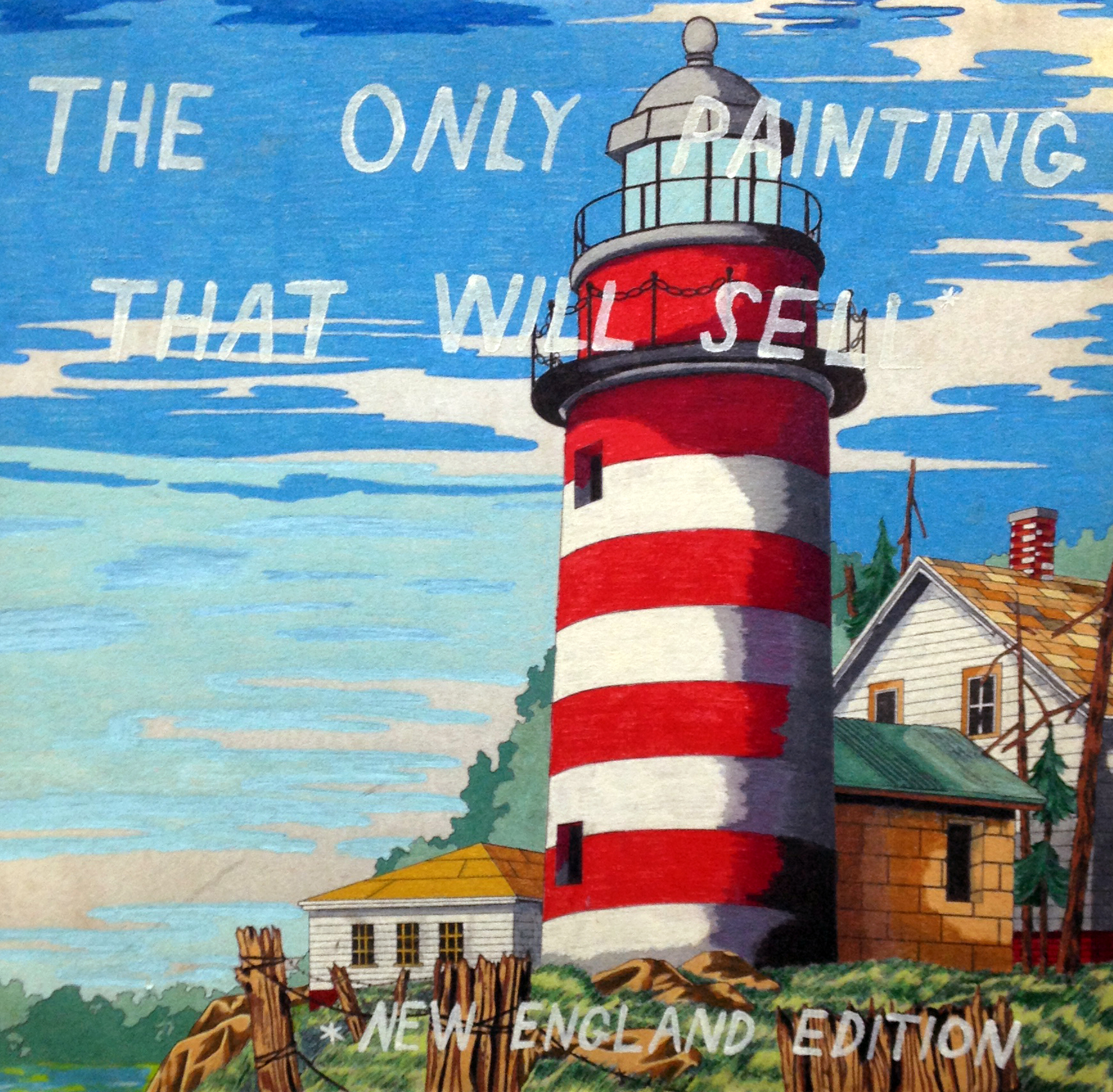

Pat Falco. The Only Painting That Will Sell, 2013. Acrylic on found painting; 18×18 inches. Courtesy the artist.

A sign peeking out from the upstairs windows of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum greets visitors as they approach the main entrance. “Insider Art” is tenderly scrawled in black acrylic across a stark white canvas; its presence is akin to a “Look Ma, I’m on TV!” poster in the background of the nightly news. This is the work of Boston-based artist Pat Falco who made his museum debut in the 2013 deCordova Biennial.

Before Falco’s name was emblazoned in vinyl on the gallery walls at the deCordova, his work graced the pages of homemade zines, signposts, t-shirts, and Tumblr feeds. In the beginning, his intention was to create affordable ways for fellow “starving artists” to patronize his work, and identify ways to bring his iconography to the masses—whether they liked it or not.

In a verdant clearing on the grounds of the deCordova sits Two Big Black Hearts (1985) by American pop artist Jim Dine. These hulking sculptures have become a regional beacon for engagement shoots, weddings, and general displays of affection. However, for the duration of the Biennial, these intimate moments are hijacked by another Falco sign that proclaims, “Premier Make-Out Opportunity.” Falco’s work is inherently subversive and his signs are his preferred method of “messing with people,” specifically people that “don’t want to look art but have to.”

Pat Falco. Premier Make-Out Opportunity installed at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, 2013. Courtesy the artist.

If given merely a cursory glance, as is often the case when mindlessly scrolling through images online, you might think Falco’s works are catchy images with snarky remarks. However, when his work is presented in a different context, in a gallery for instance, and as a collective body of work, one gains a deeper appreciation for the meaning between his one-liners.

For his current solo exhibition at Space Gallery in Portland, Maine, Falco filled every inch of the gallery with an over-the-top salon style display, which he considers not a collection of parts but a single piece of installation art. Last Place Ever features hundreds of comics, photographs, altered found objects, and works on paper that hum with life and recall the inner workings of the artist’s busy mind. The exhibit highlights not only his sharp tongue and effortless wit, but also offers a glimpse of Falco’s hopes, fears, and insecurities.

As someone who was once accustomed to showing his art on the street, knowing it would be gone by morning, Falco now operates in a world where his work is collected by the affluent. Increasingly, he is invited to break bread with the subjects that confound him; the irony is not lost on the artist.

It’s no longer enough to be a talented painter. In recent years, artists have had to cultivate additional skills, becoming networkers, teachers, and panel experts too—none of which appeals to Falco, a self-proclaimed introvert.

“Writers aren’t required to be artists, yet artists are expected to be writers. It’s not like your plumber has to prove he’s a plumber. You don’t ask for their plumber’s statement or require them to give a plumber talk in order to assess their abilities. And just because a plumber may not be an amazing public speaker, doesn’t mean they don’t know how to unclog your sink.”

Pat Falco. This Painting Would Look Good In An Expensive Home, 2013. Acrylic on found painting; 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Through his work, Falco reflects upon the absurdities, the incongruities of his profession and exposes the deficiencies of the industry in which he operates. With a single cutting phrase he challenges the invisible hand of the art market and calls into question some of the art world’s most subjective yet ubiquitous classifications. What is “low-brow” or “high-brow”? “Street art” or “fine art”? And are these designations even necessary?

Falco doesn’t purport to have the answers, but he isn’t afraid to ask the questions. And while he presents his observations as if he is an outsider looking in, I think many of us look at his work and quietly nod in agreement.