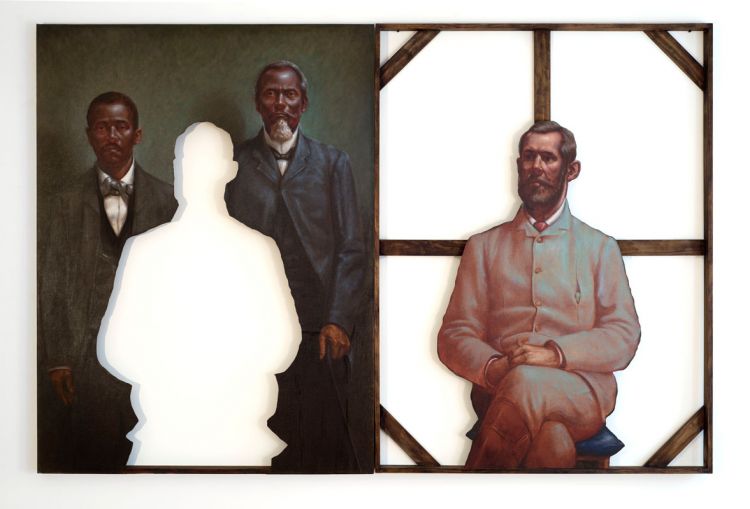

Titus Kaphar. Sacrifice (Diptych), 2011. Oil on canvas, 73 x 52 x 2 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York ©Titus Kaphar.

A canvas curtain slips from its place of prestige, revealing another that’s hidden beneath. The folds of a Thomas Jefferson portrait gracefully fall, and behind it we see an African woman bathing; her gaze at once determined, curious and solemn, as if she knows that she’s only just now being seen, but it’s already too late to matter. Titled Behind the Myth of Benevolence, this painting beautifully demonstrates the hidden histories that have been buried deep beneath the convenient narratives told in textbooks and on the news.

Titus Kaphar’s work deconstructs history and memory simultaneously, twisting familiar images to uncover those who’ve suffered under the prejudices institutionalized by the “heroes” we revere. Through The Vesper Project in 2012, he explored confabulation sculpturally, constructing chaotic scenes of a fictitious and yet misremembered 19th century house and family. In 2014 Kaphar addressed contemporary injustice with The Jerome Project, a series of small gold-leaf portraits of the men in prison who share his father’s name.

Kaphar’s paintings and installations constantly oscillate between forgotten and fiction, past and present, misremembered and myth – forcing viewers to challenge what they know, or think they know, as real.

Titus Kaphar. Behind the Myth of Benevolence, 2014. Oil on canvas, 59 x 34 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York ©Titus Kaphar.

Lindsey Davis: What led to your style of reinterpreting history through the breakdown of images?

Titus Kaphar: I’ve come to realize that all reproduction, all depiction is fiction – it’s simply a question of to what degree. As much as we try to speak to the facts of a historical incident, we often alter those facts, sometimes drastically, through the retelling itself.

Understanding this has given me the freedom to manipulate, and change historical images in a way that recharges them for me. Knowing that artists throughout time who have attempted to retell history have always embraced, whether consciously or unconsciously, a degree of fiction, in order to achieve the sentiment of the facts is liberating. Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe is one of my favorite reminders of how confounding it can be to get words, ideas and images to align.

LD: Was there any part of your childhood that informed your desire to recreate history?

TK: I think my childhood and upbringing had less to do with my desire to reconstruct history than the undergraduate curriculum of my art history education. What seemed to be obvious oversights in the canon were regularly understated, suppressed or ignored.

Titus Kaphar. The Jerome Project, 2014. Oil, gold leaf and tar on wood panel

7 × 10 ½ inches.

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York ©Titus Kaphar.

LD: What does cutting figures off at the nose or mouth signify to you? Are we all in some way helpless witnesses to the events that befall us?

TK: In The Jerome Project series the obscuring of the bottom portion of the face occurs as a result of submerging the panels in tar. This began as an attempt to visually communicate the impact that “custodial citizens” (to use a term coined by scholars Vesla Weaver and Amy Lerman) endure as a result of the criminal justice system. The portraits were submerged into tar in proportion to the amount of time the individuals had spent in prison.

After doing more research I realized that my initial formula was insufficient in its ability to communicate the impact of finding oneself in the criminal justice system. I then abandoned the formula, and the tar became symbolic in communicating the varied impact jail, prison, probation or parole has on millions of people in this country.

LD: When memories fail us by being inaccurate or not there at all, do you see your art as serving in its place, as something more real than the actual events we were trying to remember?

TK: While I was working on The Vesper Project, the issue of the way in which we recall information became an obsession for me. In waking from a dream about this project, this quote was running through my head. I still don’t know where it comes from, but I think it precisely addresses this question: “In the absence of adequate facts, our hearts rifle through memories, foraging satisfactory fictions.”

LD: How does the overwhelming tendency of the privileged to misremember history motivate your work?

TK: This tendency is not a flaw exclusive to the privileged. This is the human condition.

LD: We glorify the Founding Fathers despite the fact that they owned slaves, and most of the country still has yet to acknowledge that institutionalized racism is systemically perpetuated. What sort of revolution do you think our country needs to get its history right? Or is this even possible?

TK: I’m not sure what kind of revolution is needed to change the future, but I am optimistic that, as with all revolutions, artists will be deeply engaged in the process.