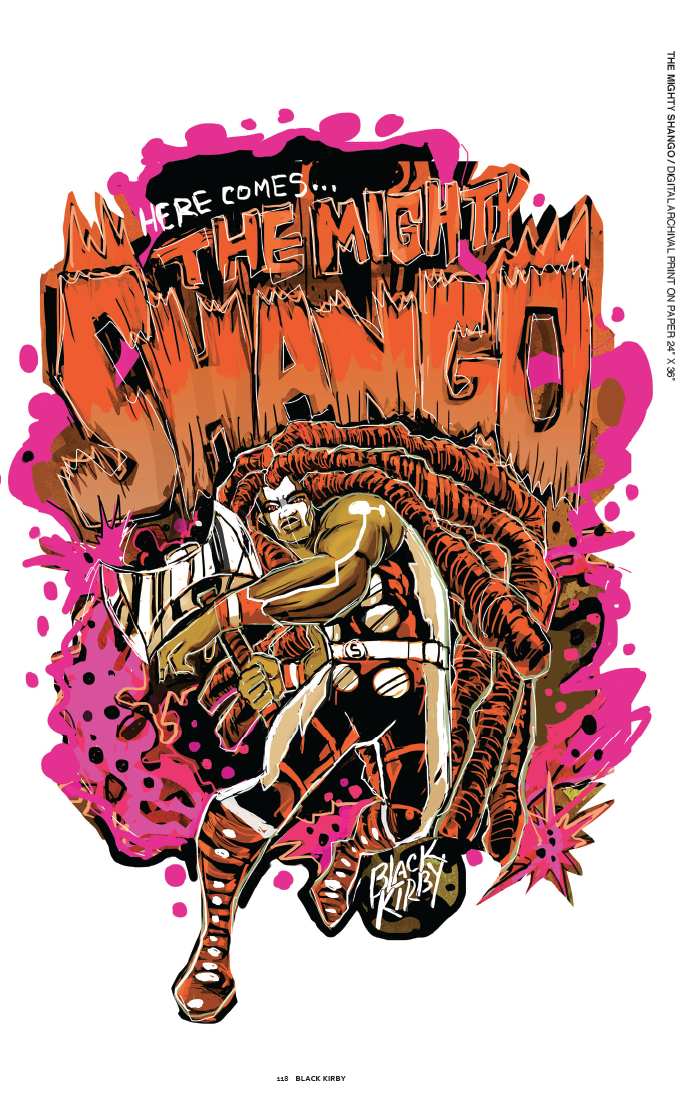

Black Kirby (John Jennings & Stacey Robinson). The Mighty Shango, 2013. Digital. Courtesy of the artist.

On January 16, 2016, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, located in Harlem, received five thousand visitors for the fourth annual Black Comic Book Festival. Comic artists and scholars from across the United States facilitated panels, workshops, film screenings, and exhibits. In the same building, a groundbreaking art exhibition was on view for its final day. Unveiling Visions: The Alchemy of the Black Imagination displayed one hundred works of art by eighty-seven artists, including album covers, comic books, novels, paintings, and electronic visualizations that foreground the “relation between design, material culture, and the centrality of black radicalism to contemporary conversations about racial politics.”[1] Here, one saw a revival of the Black Arts Movement, hereafter called the Black Speculative Arts Movement (BSAM).

Propelled by new thoughts and creative energy, members of this black speculative movement have been in creative dialogue with the boundary of space-time, the exterior of the macro-cosmos, and the interior of the micro-cosmos. Yet, there is historical precedent for this movement around the concepts of the color line, the color curtain, and the digital divide.[2]

The black speculative imagination has become the focus of numerous electronic correspondences, exhibitions, and face-to-face gatherings. The Unveiling Visions curators John Jennings—who also organized the Black Comic Book Festival—and Reynaldo Anderson used Afrofuturism to disrupt Eurocentric conceptions of identity, time, space, and ideas. Jennings and Anderson considered how digital and social-media technologies would change the landscape of political possibility; evident in what Anderson calls Afrofuturism 2.0. This is a regeneration of many of the tenets of the Black Arts Movement, of the mid-1960s through mid-1970s, which proposed a radical reordering of the Western cultural aesthetic.[3] A main tenet is the necessity for Black people to define the world in their own terms. World building is in the purview of Afrofuturism 2.0.

[In] the early 21st century, several disparate strands or elements of a new creative Africanist matrix were emerging from previous seeds planted that are adopting speculative design and world-building, a renewed political commitment, as well as the social physics of Blackness.[4]

According to Anderson, Jennings, and others, the BSAM represents different positions or bases of inquiry such as Afrofuturism, Black Futurism, African Futurism, Astro-Blackness, Afro-Surrealism, Ethno-Gothic, the Black Fantastic, and more. Transhumanism, or the use of technology or electronics to enhance the human experience, is a common theme in the BSAM. Scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Amiri Baraka wrote prescient essays about African American engagements with technology. At the turn of the twentieth century, in 1905, Du Bois described a predecessor to the Oculus Rift, a virtual-reality head-mounted display, called The Megascope.

With one more swinging of the lever there swept down before the window a great tube, like a great golden trumpet with the flare toward us and the mouth-piece pointed toward the glit[t]ering sphere; laced round it ran silken cords like coiled electric wire ending in handles, globes and collar like appendages.[5]

Du Bois wrote about another device that layers a “thin transparent film” on top of another—like Lev Manovich’s “augmented space,” a physical space overlaid with dynamically changing information.[6] Nearly seventy years after Du Bois, Amiri Baraka, one of the founders of the Black Arts Movement, wrote about technology as a form of consciousness. Baraka envisioned a word-placing machine that utilizes more than just fingers or body parts and represents three-dimensional ideas.[7] In the book Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, I explore the possibilities of reconceptualizing artifacts such as African cosmograms as cultural devices to create augmented space. I call this development Afrofuturism 3.0.[8]

Wangechi Mutu. Non je ne regrette rien, 2007. Ink, paint, mixed media, plant material and plastic pearls on mylar, 54 x 87 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.

Intertextuality, a narrative device that connects a text to other outer texts, can be used to contain or juxtapose multiple genres and themes.[9] A concurrent presence of texts is shown in Wangechi Mutu’s collage, Non je ne regrette rien (2007)—the title refers to the French singer, Edith Piaf— in which a black, female body absorbs the cyborg, colonialism, technology, and nature. The Nigerian-born, US-based artist Fatimah Tuggar conflates ideas about race, gender, and class, disturbing Western notions of subjectivity. Grafrofuturism, by the Boston artist Barrington Edwards, merges graffiti art with African robots. Black Kirby, a collaboration between John Jennings and Stacey Robinson, functions as a rhetorical tool by appropriating the work of Jack Kirby, a twentieth-century White American comic-book artist. Combining Kirby’s bold forms and energetic ideas with themes centered around Afrofuturism, social justice, representation, and magical realism, it uses the culture of hip hop as a methodology for creating visual communication.

Black Kirby (John Jennings & Stacey Robinson). Major Sankofa, 2013. Digital. Courtesy of the artist.

Black speculative artists, scholars, and writers re-envision dominant cultural themes through cultural production that isn’t concerned just with the future but also with “engineering feedback between its preferred future and its becoming present.”[10] The BSAM’s practitioners “re-see” mythologies, fictions, and histories that originate in science fiction and extend to functional technologies of the present. Sonic fictions in scientific and speculative formulations such as data visualizations, film, literature, and the arts have historical and cultural significance. The BSAM reveals a mythos or ethos around what has already been established, using political or techno-cultural lenses. On the horizon and beyond the speculative are Afrofuturistic engagements in science, technology, engineering, art, and math (STEAM) that move practitioners to the center of artistic, professional, and academic discourse.

[1] Tiffany Barber, “Art, Futurism, and the Black Imagination,” New York Public Library Blog, September 29, 2015; accessed January 25, 2016.

[2] Reynaldo Anderson, “Afrofuturism 2.0 and the Black Speculative Art Movement: Notes on a Manifesto,” How We Get to Next, January 22, 2016; accessed January 25, 2016.

[3] Larry Neal, “The Black Arts Movement,” Drama Review, Summer 1968, excerpted in National Humanities Center, The Making of African American Identity, Vol. III, 1917–1968; accessed February 14, 2016.

See also: Larry Neal, Visions of a Liberated Future: Black Arts Movement Writings, ed. Michael Schwartz (New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 1989).

[4] Anderson.

[5] W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Princess Steel,” 1905?, p. 824, W.E.B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

[6] Du Bois, 823. Lev Manovich, “The Poetics of Augmented Space,” Visual Communication 5, no. 2 (June 2006): 219–240, accessed February 14, 2016.

[7] Imamu Amiri Baraka, “Technology and Ethos,” in Raise Rage Rays Raze: Essays Since 1965 (New York: Random House, 1971), accessed February 14, 2016.

[8] Nettrice Gaskins, “Afrofuturism 3.0: Vernacular Cartography and Augmented Space” in Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, ed. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles Jones (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2016).

[9] Julia Kristeva, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art (New York: Columbia University, 1980), 69, quoted in Karin Wenz, “Intertextuality as Spatialization,” accessed February 14, 2016.

[10] Kodwo Eshun, “Further Considerations on Afrofuturism,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 287–302, accessed February 14, 2016.