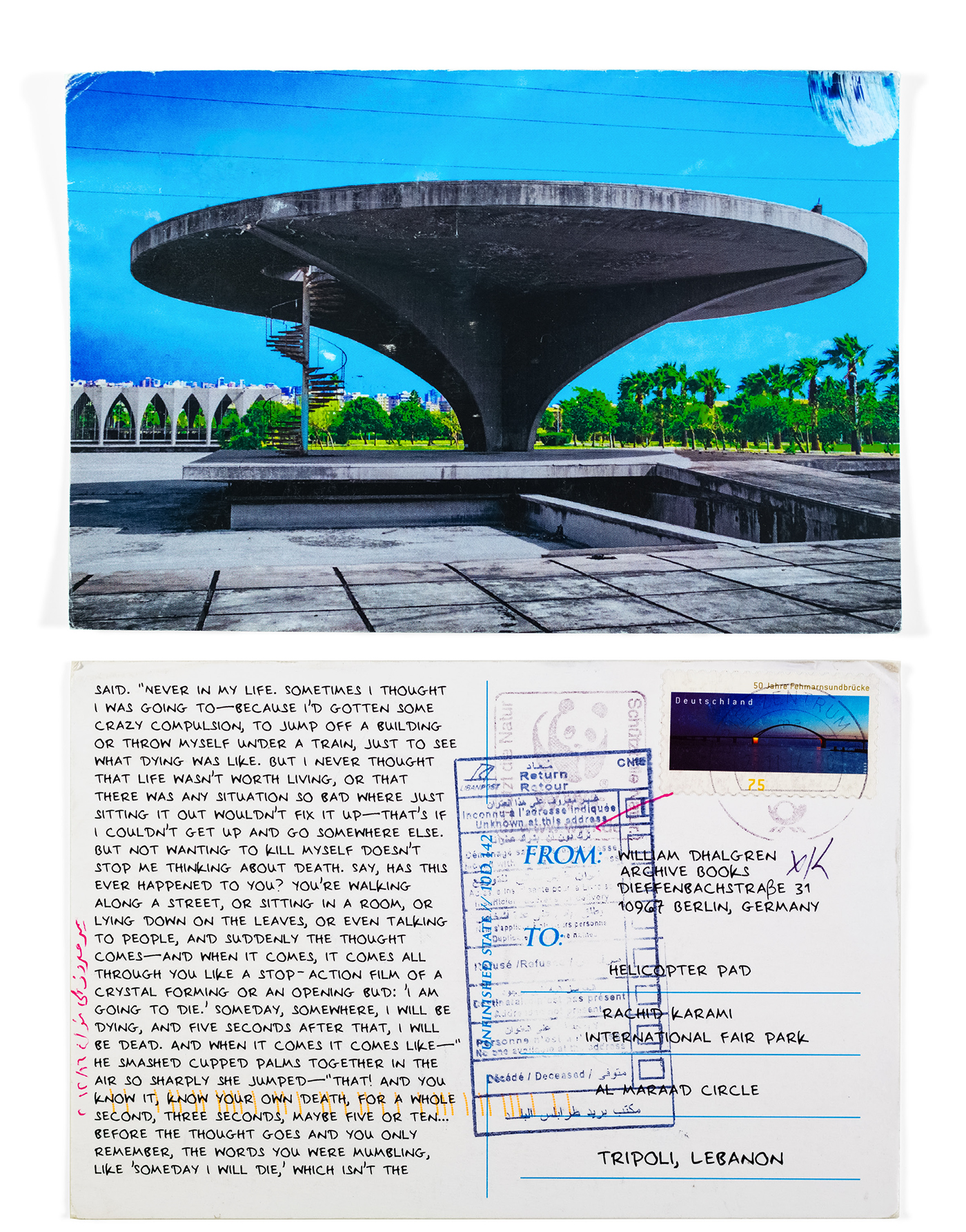

Caitlin Berrigan. Helicopter Pad, Rachid Karami International Fair Park, from Unfinished State, 2015. Postcard from series; 14.8 x 10 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Caitlin Berrigan.

Caitlin Berrigan’s Unfinished State is an ongoing project and the title of a book encompassing postcards, photographs, and writings. The book’s contents explore how conflict has affected the real estate development, property distribution, and landscape of the country of Lebanon. Spanning several decades, the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90) produced an abundance of buildings throughout the country that are stuck in the beginning stages of development: concrete armatures of unfinished structures, forming a web of ghost architecture fixed in time. Berrigan, an artist who works across spatial and temporal media, has endeavored in her project to renew the collective imagination of possible futures for these buildings and the landscape of Lebanon. Unfinished State moves across science fiction and forgotten environments, complicated by present systems of power.

The project began in April 2010 when Berrigan, who was living in Berlin, Germany, visited a friend in Lebanon. For one month, Berrigan traveled around the country. The book organizes her travels, including many return trips to Lebanon, from north to south, beginning in Tripoli and moving along the coast to Beirut and Tyre. Nearly six years later, I met with Berrigan at her apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York to talk about this project. She described many of the buildings in Lebanon as “empty shells of concrete, façades enclosing voids.”1 These enclosures were mostly vacant, sometimes attended by guardians. These hollow environments were striking to her.

Caitlin Berrigan. Burj El Murr Tower, On the Corner of Army and General Foaad Chebab, from Unfinished State, 2015. Postcard from series; 14.8 x 10 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Caitlin Berrigan.

In Lebanon, these unresolved structures mar the coastal landscape in a particular way: they evince the history of conflict through stagnating structures forever poised with potential. These projects—including anonymous apartment complexes, mosques, skyscrapers, and also notable projects such as the Rachid Karami International Fair in Tripoli by the Brazilian architect, Oscar Niemeyer—have been halted in a state of incompletion. Contrary to the aggressive aura of an urban landscape ravaged by the physical destruction of war, these buildings are the casualties of a post-conflict economy, explained Berrigan. Progress was complicated or terminated by the war, so these structures have remained frozen in time and embodied with a longing for futures that never materialized.

Returning to Berlin, Berrigan considered how she could revitalize these architectural specters. “I wanted to envision a different narrative for these unfinished projects outside of the micro-histories of conflict and capitalism in Lebanon,” she said. To spin a new narrative, Berrigan decided to send the buildings a story, the text of a novel broken into fragments for each building. She chose the circuitous, post-apocalyptic work of speculative fiction, Dhalgren, by Samuel Delany, which takes place in Bellona, a bombed-out city in the American Midwest. The narrator of the novel, an amnesiac who cannot remember his own name, is unreliable. Berrigan pointed out that while architecture can become embedded into a linear or visual history of a place, the scenery of Lebanon is not an account of the passing of time; instead, these concrete foundations represent the slowing or stopping of time. Like Dhalgren’s unnamed—or, more accurately, incorrectly named—narrator, these buildings are not credible sources.

Berrigan discovered that the conception of space within Lebanon is also not straightforward. There are places without names, places with multiple names, and spaces described in relation to other buildings, even buildings that no longer exist. In this way, spaces are described equally by presence and absence. For example, a person would give directions such as, “Across the street from where the Italian bank used to be.” Over several decades, the unfinished buildings have become accepted in their suspended states. Moreover, the Lebanese postal system does not rely on numbers but on relational descriptions of named places to deliver mail. Buildings, such as the ones that Berrigan documented, can be located by their physical and remembered surroundings.

Beginning in February 2015, Berrigan sent more than a thousand postcards to these locations. To each building or structure, she sent a postcard with an image of the destination on the front and an excerpt of Dhalgren on the reverse. Many postcards were lost, some may have been delivered, and nearly two hundred were sent over several months to the return address, on the postcard’s back. These returned postcards form a new narrative, funneled through a postal system without address numbers in search of sites that lack a consistent convention of naming. The perforations in the plot of the reassembled text mirror the style of Delany’s writing: fragmentary and reluctant to resolve itself.

To date, Unfinished State continues. The project began with photographs accompanied by transcribed fragments of a science-fiction novel, which were then printed onto postcards and addressed to sites throughout Lebanon. The collected postcards have been codified into a book to be published this summer by Archive Books, in Berlin. This book features edited conversations with artists Haseeb Ahmed, Mirene Arsanios, Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga, Franziska Pierwoss, and Caleb Waldorf, and covers topics as varied as practice, imagination, space, and real estate. In addition, Berrigan is currently working on a related video that takes place between Berlin and Beirut. Meanwhile in Lebanon, many of the locations—the subjects of the forthcoming video and book—remain unfinished.

Caitlin Berrigan has created special commissions for the Whitney Museum of American Art, Harvard Carpenter Center, and the deCordova Museum. Her work has been shown at Storefront for Art and Architecture, Hammer Museum, Anthology Film Archives, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Vancouver Olympics, among other venues. She has received fellowships and residencies from the Humboldt Foundation, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and Program (a Berlin-based nonprofit project for art and architecture), and she is a 2015–17 Schloss Solitude fellow. She teaches emerging media in the photography and imaging department at New York University Tisch School of the Arts, and holds a master’s in visual art from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a BA from Hampshire College.

1. All of Berrigan’s quotes are from a conversation with the author, on February 26, 2016, in New York City, New York.