Before Pictures, the new book by the renowned critic and art historian, Douglas Crimp, opens with a family snapshot of Lake Coeur d’Alene in the northwest corner of Idaho. The image is idyllic and could serve as a postcard, but as he explains, “Growing up in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, a small town as notorious for its xenophobia as renowned for its natural beauty, made me want to live in a big city even before I’d seen one.”

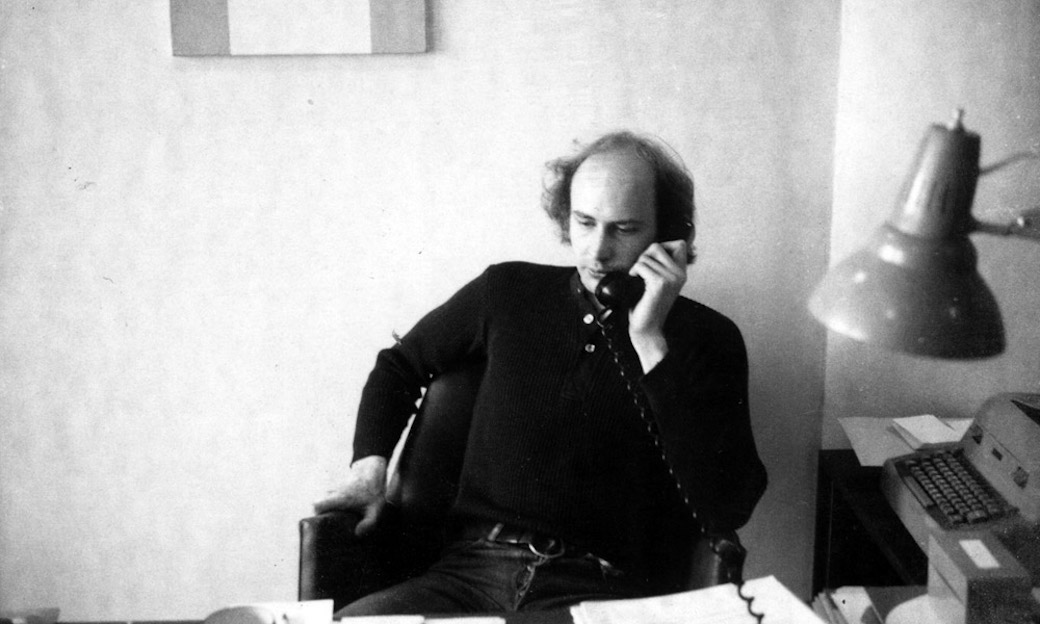

Crimp moved to Manhattan in 1968 and continues to live there today. Before Pictures chronicles his first decade living in New York City and concludes with Pictures, a groundbreaking exhibition he organized at Artists Space in 1977. The book is rich with personal photographs, artworks, film stills, and various ephemera and is written in clear, conversational prose. While his book does not fit into the conventions of a memoir, Crimp is generous in his introspection and looks critically at the art world, the gay world, and the spaces in between.

Mimi Cheng: While reading Before Pictures, I was struck by the way in which a sense of humor emerges in your prose. Is humor something you were consciously exploring?

Douglas Crimp: I had some funny stories I knew I wanted to tell, like one about getting my first job at the Guggenheim because they were doing a show of pre-Columbian Peruvian art, and Ethel Skull carried a gold jaguar figurine on a pillow at the opening—it was actually from the wrong pre-Columbian culture. Or the story about my evening with the decorator with a penchant for unicorns. I discovered other comical stories through my research, including one about the Watergate criminals in the basement of the East Wing of the White House, assembled to watch Tricia’s Wedding, the film by The Cockettes. The book’s purpose is, to my mind, fairly serious—to juxtapose the experimental art scene with the experimental gay scene of 1970s New York. Sometimes that juxtaposition is automatically funny, and sometimes it is leavened by a good story. Most of the book’s chapters were written initially to be lectures, and humor is often something I use to capture an audience.

The cover of Before Pictures. Published by University of Chicago Press, October 2016.

MC: The book is divided into five sections, each titled after the address of one of your former apartments in New York City, as well as the years in which you lived there. The artist Zoe Leonard photographed each building and its closest subway stop, and these images are used to illustrate each section. Why did you choose to structure the book this way? What do these photographs evoke for you?

DC: I didn’t initially structure the book this way. The eight chapters are structured around professional things that I did in the decade before the Pictures show—working as a curatorial assistant at the Guggenheim Museum, organizing an Agnes Martin exhibition, writing reviews for Art News, and so forth. At some point, I noted on the table of contents, just for the purpose of figuring it out for myself, which of the five buildings I was living in at the time covered in a particular chapter. I sent that version of the table of contents to my editors at Dancing Foxes Press, and they liked the idea of indicating the parts of town where I was living. Joseph Logan, the book designer, also noted that every time I moved, I went farther downtown—from Spanish Harlem, to Chelsea, to Greenwich Village, to Tribeca, to the Financial District. So we thought we would mark these locations with photographs of the buildings. We talked about finding very ordinary photographs, something like the building facades that Hans Haacke used in his Shapolsky piece. But where would we find such photographs? I suddenly had the idea of asking Zoe, who had made two books with Karen Kelly and Barbara Shroeder [of Dancing Foxes Press] and who has been my friend since our ACT UP days, beginning in the late 1980s. Zoe agreed right away, and I took her on a tour of the buildings. Before the end of that tour—when we were on Chambers Street, I believe—she began to think about the nearby subway stops. After some months, Zoe delivered the contact sheets from her shoots. Joseph took one look at them and said, “These are Zoe Leonard artworks!” And of course he was right. They are such beautiful photographs. We decided very quickly to do double-page spreads and to use one on the cover. In the meantime, I had wanted to use the 1972 New York subway map designed by Massimo Vignelli, which I had always loved but which didn’t last long [in actual use]—people claimed they couldn’t read it because it was so stylized. Joseph came up with the idea of using it for the endpapers. So, with Zoe’s photograph taken in the subway as the cover image and five more facing those of the facades of the five buildings I’ve lived in, we had a geographical organization of the book along with the chronological one. The photographs transform the book visually. The book is very generously illustrated, with many different kinds of photographs—snapshots, fashion photos, film stills, works of art and architecture—in both color and black-and-white. The double-page spreads of Zoe’s photographs punctuate this multiplicity of image types five times and thereby make the whole book coherent in a new way. Everyone remarks on how extraordinary Zoe’s photographs are.

MC: In the chapter “Action Around the Edges,” you consider the abandoned industrial piers that ran along the Hudson River as both a cruising ground for the gay community and a generative site for artists like Gordon Matta-Clark and Vito Acconci. I’m interested in your relationship to the piers, and the way you navigated their simultaneous dangers and temptations. Can you expand on this?

DC: In retrospect, like many things that I write about in this book, I wish I’d been more conscious, at the time, of how extraordinary these haunts were. I remember that, because of the disintegrating wooden parts of the piers, there seemed always to be a light dust in the air [inside them], so that when the sun poured through holes in the roof, there would be a kind of golden aureole. That was so beautiful! [As with my feelings about] the Paradise Garage, which I mention in my chapter on disco, I wish I’d gone to the piers more often than I did. There was nothing like them, and of course there’s nothing like them now. They were the product of a particular moment in history, the moment of New York City’s deindustrialization. I took their existence for granted, and then they disappeared. I probably went less often than I now wish I had because they were indeed dangerous, especially at night. But I also think the sexual temptations at the piers were of a fairly kinky variety, and I hadn’t yet fully accepted that aspect of my psyche.

Opening of Pictures at Artists Space, September 1977. Photo by D. James Dee. Courtesy of Artists Space.

MC: Would you consider the book to be a queer narrative of New York City in the 1970s?

DC: Before Pictures has its origin in my ACT UP days, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. My then-new activist friends were mostly a generation younger than me and hadn’t experienced the thrilling explosion of gay, public, sexual culture in the 1970s that I had. We all agreed on the need to combat the revisionist view of that culture being perpetrated by writers like Randy Shilts and Larry Kramer—the view that the 1970s represented gay men’s immaturity and caused the AIDS epidemic, which then made us grow up to be proper citizens. My ACT UP friends sometimes responded to my stories of those years by saying, “You should write a book about gay New York in the 1970s,” thinking that such a book might counter the revisionist narrative. I wasn’t sure I would do that, but the seed was planted. Much time went by, and eventually I embarked on the present book. It’s obviously not simply a book about that gay sexual culture because it’s also about so much else. It’s about the transformation of the city and artistic experimentation. But it’s also about the gay sexual scene, as I lived it. And to the extent that it combines all of those things—that it combines autobiographical anecdotes with criticism and cultural history and is, in fact, a genre hybrid—to that extent I like to think of what I do in the book as queering 1970s New York.

MC: I recently revisited your essay “Mourning and Militancy,” which was published in the journal October in 1989, and I was particularly attuned to your thoughts on representation, resistance, and what you call “the violence of silence and omission.” How would you position the essay today?

DC: “Mourning and Militancy” was a turning point in my AIDS writing, which I indicated in the related title of my collected AIDS writings, Melancholia and Moralism (2002). It was the moment when I began to write about myself as a means of analyzing the situation we AIDS activists were confronting. Acknowledging my subjectivity has been an essential part of my writing since then, something I attempted to theorize in my 1999 essay, “Getting the Warhol We Deserve.” Less than a week after Donald Trump’s election, I’ve received several inquiries about what lessons AIDS activism might teach us about the terrifying situation we now face. I think people find some solace in the fact that ACT UP won some important political battles in the face of government inaction and outright hostility—changing the way people with AIDS were represented and treated, streamlining the drug-approval process, and so forth. But many of the issues we faced then we still face, and face all the more now because of the extreme right’s ascendance—income inequality (remember, it was during Reagan’s presidency that the transfer of wealth from the poorest to the richest Americans began in earnest), an unfair and otherwise broken healthcare system, racism, misogyny, and—despite the legalization of gay marriage—homophobia.