FLASH POINTS is a regular conversational series that focuses on issues relevant to the state of the art world at large, contemporary art education, and issues artists face today. You can participate by contributing feedback, posing a follow-up question, sharing anecdotes, or suggesting new topics in the comments area below.

Up next on Flash Points, we introduce the topic of Art + Politics. Yes, we unashamedly admit, this is a timely topic riding the wave of excitement of Barack Obama becoming the nation’s first African-American President. But more broadly, the subject of art and politics has created countless books, symposia, exhibitions, and activist projects. Over the next six weeks we’ll explore the diverse ways that art and politics intersect, inform, overlap, and challenge each other. It is our hope that a discussion here on Flash Points will provide additional insight into the role of art in this particular moment in time. Is art inherently political, regardless of its intentions or motives? What role has political art played both in the history of art but also in the broader context of history? Can and will art participate in this new mandate of “change,” and if so, how?

Hans Haacke, MoMA Poll (1970)

Artists often deploy their work strategically to engage viewers in critical inquiry of social, economic, and political issues that define a particular moment. The 1970 work MoMA Poll, by Hans Haacke, asked viewers to answer the question, “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina Policy be a reason for you not voting for him in November?” Museum-goers could vote and the results were visually represented in transparent ballot boxes. The artwork served as a form of political engagement in two ways. Not only did it function as a political poll, testing the unpopularity of Vietnam, but it also served as a form of institutional critique, as the Governor also served as a trustee of the Museum.

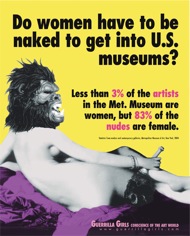

Defining movements in our national history like the Civil Rights Movement, the Anti-War Movement, the Gay Liberation Front, Feminism, Black Power, immigrant rights, and labor movements have greatly impacted our collective political and cultural memory. These social organizations and the significant issues they have addressed have provided additional opportunities and strategies for artists to work towards specific goals. In the 1980s, groups like the Guerilla Girls, Gran Fury, Group Material, and Colab took issues that were not seen as particularly political, such as the lack of female representation in museums and the AIDS crisis, and politicized them through dissemination of provocative images and information. Silence=Death, created by Gran Fury and adopted by the activist group Act-Up, is still a well-recognized icon now synonymous with HIV/AIDS activism. Both of these collectives waged media wars through art to draw attention to their causes, but they also battled with the Reagan administration and the political system as well. These are just two examples, but does art have to be partisan to be political?

Guerilla Girls, Do women have to be naked to get into U.S. museums? (2007) and Gran Fury, Silence=Death (1987)

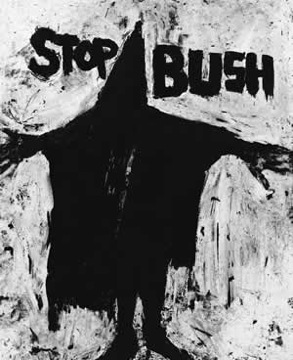

Art consistently toys with notions of power, whether to comment on the horrors of war, as evidenced in the work of artists such as Richard Serra (Season 1) as well as other Art21 artists including Nancy Spero, Alfredo Jaar, and Jenny Holzer (all Season 4), or to pay homage to powerful figures, as reflected in more traditional forms such as monuments, presidential portraits, and religious imagery.

Richard Serra, Stop Bush (2004)

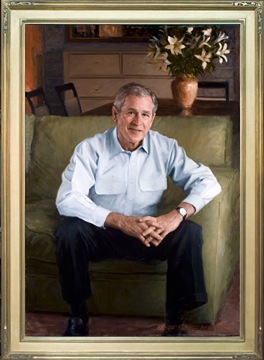

On the other hand, art can also serve the controversial function of propaganda, looking back upon court painters like Jacques-Louis David and Diego Velasquez to today’s Venice Biennale positioning contemporary artists as nation builders. What are the ties binding art, power, and patronage? Below is a recent portrait of George W. Bush that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. with a caption that reads, “. . . Bush found his two terms in office instead marked by a series of cataclysmic events: the attacks on September 11, 2001 which led to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina; and a financial crisis during his last months in office.” After much protest, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont persuaded the Smithsonian Institution to remove “led to” from the caption.

Robert Anderson, George W. Bush (2008)

To get the conversation started, here’s a recap of some of the questions we’ll be exploring in the coming weeks. Please help us frame the discussion by leaving a comment below.

- Is art inherently political, regardless of its intentions or motives or does art have to be partisan to be political?

- What role has political art played both in the history of art but also in the broader context of history?

- What ties bind art, power, and patronage?

- Can and will art participate in this new mandate of “change,” and if so, how?

Pingback: Aestheticized Politics | Creative Contact

Pingback: Flash Points: Art+Politics, Looking Back & Moving Forward | Art21 Blog

Pingback: future cities lab » Sensing the City - Design Studio with Wendy Ju - Fall 2010

Pingback: Corie Cole: Landscape with the Fall of Torrijos | Art ExAlt

Pingback: 237.130_1601_WLGN_Task3_Critically Reading and Thinking_06-04-16 – lianeclose