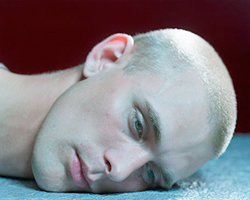

Michael Rakowitz, "paraSITE," 1998-present.

This weekend I went to an opening at The Soap Factory, a scrappy and often-excellent nonprofit art space a block or so off Minneapolis’ riverfront. The description of the work, a Clive Murphy installation called Almost Nothing, was intriguing enough to draw me there: he’d filled the entire space with a series of air-filled tubes created from black plastic garbage bags, mimicking the architectural geometry of the space—which, as its name states, was once a soap-making factory, reeking of lye.

But when I arrived, the piece immediately struck me as so much hot air. Here’s my progression of thought: it’s February in Minnesota. This building is virtually unheated. We’re facing twin catastrophes of economic downturn and human-made climate change. And this guy’s art requires electric air blowers to drone constantly on whenever the gallery’s open?

Murphy’s work is what it is—a project influenced by “radical architectural proposals from the sixties” and inflatable carnival games that examine “themes of hierarchy, inter-relationality, and meaning formation”—and I don’t knock it for that. But it isn’t what I’ve been looking for lately: contemporary art with immediacy, that pragmatically or poetically addresses the challenges we face today. Not all art needs to do that, but it’s what I’m looking for. Something more along the lines of another inflatable-bag art project: paraSITE, in which artist Michael Rakowitz collaborated with homeless people to construct temporary inflatable housing designed to leech warmth from heat outtakes from apartment buildings.

In considering “political” art—especially in a non-election year, especially facing the economic and environmental problems we do—I’m reluctantly coming to believe that art doesn’t have the power I once believed it did for bringing about social change.

Suzanne Opton's "Soldier: Birkholz" billboard

Perhaps it’s creeping cynicism. As a journalist covering the Republican National Convention in St. Paul this fall, I saw magnificent, irreverent and funny artworks – from full-fledged contemporary artworks (including Ligorano/Reese’s The State of Things, gigantic ice letters spelling out the word DEMOCRACY, which melted away on the capitol lawn as time passed, or Suzanne Opton’s Soldiers billboard series) to creative protest signs and hilarious chants by nonviolent demonstrators (“You’re hot, you’re cute, take off your riot suit!”). Still, the police crackdown was powerful, unrelenting and sometimes violent—and, if hearing from Republican delegates on the convention floor is any indicator, protesters’ messages didn’t seem to register. The art was dismissed as mere protest.

My doubts also have to do with responses to my oft-asked (and admittedly naïve) question, “Can art change the world?” As an editor at the Walker Art Center and at Adbusters Magazine, I posed the question to a number of people: critic Robert Storr; artists Rirkrit Tiravanija, Sam Durant, and Thomas Hirschhorn; Artforum editor Tim Griffin and independent curator Hou Hanru, to name a few. While they all said they hoped it had that kind of power, few wholeheartedly agreed it did.

But from some of these same people, I found hope for smaller incremental change—one heart (or mind) at a time, perhaps.

During a residency at the Walker, Art21 artist Guillermo Calzadilla told me his take. Art, unlike protest, is difficult to pin down, he said, and therein lies its power. Overt agit-prop is easy to spot, categorize, and therefore dismiss wholesale by opponents of the message it carries. But art is something… else. Something nebulous and multidimensional and hard to get one’s brain around.

Before we can dismiss it, we have to figure out what it is.

The point was illustrated last week by the novelist Haruki Murakami. Despite being threatened with boycotts by activists outraged by Israel’s overwhelming use of force in Gaza last month, he traveled to Israel to accept the Jerusalem Prize for literature. His speech began in a writerly fashion, musing on the novelist’s role as a “professional spinner of lies”—hardly the ranting of an anti-war zealot.

Haruki Murakami (Wikipedia)

But as he progressed, he worked in mention of a UN report that “more than a thousand people had lost their lives in the blockaded Gaza City, many of them unarmed citizens” and of “white phosphorus shells,” a weapon banned from use in civilian areas, but allegedly used by the IDF. “I do not intend to stand before you today delivering a direct political message,” he said, before launching into a scathingly poetic message, the kind perhaps an artist is best suited for delivering:

Please do, however, allow me to deliver one very personal message… [I]t goes something like this:

“Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg.”

…What is the meaning of this metaphor? In some cases, it is all too simple and clear. Bombers and tanks and rockets and white phosphorus shells are that high, solid wall. The eggs are the unarmed civilians who are crushed and burned and shot by them. This is one meaning of the metaphor.

This is not all, though. It carries a deeper meaning. Think of it this way. Each of us is, more or less, an egg. Each of us is a unique, irreplaceable soul enclosed in a fragile shell. This is true of me, and it is true of each of you. And each of us, to a greater or lesser degree, is confronting a high, solid wall. The wall has a name: It is The System. The System is supposed to protect us, but sometimes it takes on a life of its own, and then it begins to kill us and cause us to kill others—coldly, efficiently, systematically.

I have only one reason to write novels, and that is to bring the dignity of the individual soul to the surface and shine a light upon it. The purpose of a story is to sound an alarm, to keep a light trained on The System in order to prevent it from tangling our souls in its web and demeaning them. I fully believe it is the novelist’s job to keep trying to clarify the uniqueness of each individual soul by writing stories—stories of life and death, stories of love, stories that make people cry and quake with fear and shake with laughter. This is why we go on, day after day, concocting fictions with utter seriousness.

Is that a critique? Mere poetry? Both?

When I asked Hou Hanru about a piece of “political” visual art that affected him powerfully, he named an oft-cited work by David Hammons.

“He was selling snowballs in Brooklyn on the street in the winter. He made different snowballs of different sizes, and he was selling them at different prices. This was such a strong critique about the logic of consumption society and behind it, of course, was the whole notion between white and black and all these social issues. A simple gesture like this can, because the complexity being expressed through a very simple action, the tension between this simplicity and complexity, make a very strong social statement.”

And one that, unlike an anti-John McCain poster pinned forever to Fall 2008, still has resonance many years later.

Citing Joseph Beuys, Hanru summed up the thinking well: “I think his way of trying to change things is more metaphysical somehow.”

Art didn’t overturn Israel’s policies about Gaza. Art didn’t shut down the RNC, result in any changes in the GOP platform, or prevent the concussion grenades from being fired. But I sincerely doubt art did nothing. Perhaps it laid a thought, the sliver of a doubt or the germ of an alternative way of thinking in the minds of people, delegates and demonstrators, lovers of literature and Israeli politicians.

This week, I’ll be looking at some of these kinds of art. Art that I hold no illusions will up and alter the face of history, but that I do have hope will at least plant a seed.

Pingback: Abstract Archive › The Haps