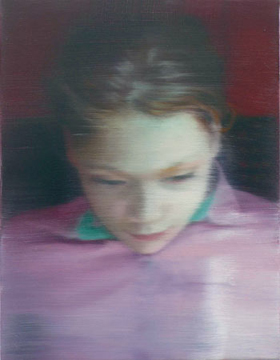

Gerhard Richter, "Ella'" (2007)

I didn’t expect to crack a smile during the new show of Gerhard Richter’s portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery. Especially at a Gerhard Richter show. He is an artist routinely and tiresomely referred to as “the world’s best living painter” (the title is on a four-months-of-the-year timeshare with Jasper Johns and Lucian Freud) and whose work, we are constantly informed, waggle-fingeredly, is an “exploration of painterly potential” in “various painting strategies” with “a bewildering array of subject matter” (so a lazy Google search informs me). The Richter rhetoric is all stoic sobriety. The joyful physicality of applying paint to a canvas has been expunged from Richter’s careful, detached, restrained work. Serious as cancer. Or so we’re told. (The truth is that it’s the writing on Richter that’s had all the joy sucked out of it).

The first and perhaps most unexpected thing about the Richter show is its venue. The National Portrait Gallery (an anachronism as weird as a National Still Life Gallery, or a National Gallery of Pictures of Pigs) has a huge collection of portraiture from early Tudor royalty to contemporary celebrity politicians and athletes, whose quality veers wildly from the awesome (early Tudor royalty) to the awful (contemporary celebrity politicians and athletes). It’s a museum that values subject over style and for every great painting, there’s another ham-fisted one that sneaked in by virtue of its painter’s popularity among 19th-century personalities who insisted on getting their beards just right.

Strange then to see, installed in its vertiginous entrance hall over the escalator, Richter’s 48 Portraits (1971-2), his passport-photo-style photorealist paintings of famous men from the turn of the 20th century (Wilde, Hindemith, Greene, Stravinsky, Einstein, and so on), arranged in an inverted right-angled triangle. One response to this somewhat anachronistic placing (they’re portraits, but painted meticulously from posed photographs, and sidestep any claims to ‘likeness’, ‘presence,’ or ‘essence’ that are part of the armory of conventional portraiture) is that it’s a piece of ‘institutional critique,’ the process by which a hoary old institution tries to look self-deprecating by inviting artists to carefully (“just in that corner, please”) make fun of their collection and organization. It’s an old trick that rarely looks anything other than self-aggrandizing. Here, though, the joke is on the artist, not the institution. And it’s fascinating.

Richter’s much-quoted statements about the inefficacy of painting to capture the essence of its subject—a somewhat haughty riposte to anyone daring to find emotional import in his works—may be plastered in the wall texts and carefully parsed on the NPG website, but the nature of the exhibition and its location enable a reading that breathes life into an artist that attracts conventional wisdom as feces does flies. By wrestling the big man’s knowingly sprawling oeuvre (no surprise that his ongoing collection of photographic source material is given the daunting title of Atlas) into the category of portraiture, the show opens up Richter’s work in a way belied by the standard ‘anti-style’ readings. While the artist may make the somewhat laborious claim that “a portrait must not express anything of the sitter’s ‘soul’, essence, or character,” it’s hard to not look at his painting of his daughter Ella from 2007—she looks down, lost in a book, like a version of his earlier Reading from SFMOMA—as tender and rather protective, for all its petulant I-don’t-care-really fudged paint. (I was reminded of Matisse’s great 1905 Girl Reading, another image of a father watching his daughter’s absorption in something other than him. In both paintings the brushstrokes—one smeared, one electrified—look like cries for attention from childish papa).

For all his protestations, this show, in its dogged refusal to swallow the artist’s mythology whole, situates Richter as a romantic in spite of himself. Look at his 1996 Self Portrait: the artist looks down (again swerving away from what a direct gaze might give away) through a fog of squeegeed oil paint, as though behind frosted glass. At the edges of the painting the artist has meticulously rendered the cracks and chips of a battered Old Master, a visual gag that’s really half-serious. Well, I laughed.

Pingback: Letter from London: Richter Scale | Art21 Blog | ArtistArray.Com