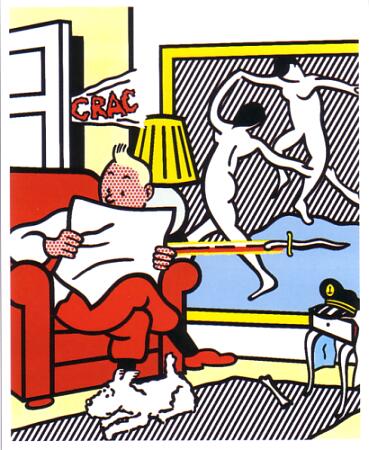

Roy Lichtenstein, "Tintin in the New World," 1993

(Disclaimer: this Letter from London is actually from Paris. Apologies.)

Speaking French makes your mouth assume a range of attractive poses, which is why I always say the word boulangerie while being photographed (try it). French confers an instant silken attractiveness to banal things like English people’s faces. The French term Bande Dessinée (BD), for instance, makes its English equivalent—comic strips—sound infantile and crude, the province of mooby monomaniacs in lightless basements. Hence the new show at the Maison Rouge, Paris, Vraoum! Treasures [my translation] of Bande Dessinée and Contemporary Art, sounds so much more intellectually refined than a similar show would in the UK or US. (Even that Vraoum! is the sound of a very nice car being driven past you at speed by a man called Jean-Baptiste with a flowing white silk scarf, whereas our Whoosh! or Whizz! is an out-of-control jalopy driven by a pack of wise-cracking rodents).

As befits their illustrious-sounding name, BD’s have a particularly elevated status in France, and it’s a much better term for the richness of a genre which includes amazing geniuses like Chris Ware, Ben Katchor, Daniel Clowes, and Alison Bechdel, not to mention the earlyand mid-twentieth century pioneers of the genre (of which more later). For me, graphic novels means Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Henry Miller, so that’s out. It’ll have to be “comic strips” until something better comes along. The tricky nomenclature is fitting, since the comic strip genre has been so twisted and transformed over the last hundred years that it contains its own accelerated art history, its baroques and gothics and rococos, perennially postmodern before anyone else cottoned on. But they did eventually, and like an old soak at a children’s party, modern art crashed in, reeking of discount vodka and pomposity, and the relationship (here’s where the metaphor has to stop) has veered between doting and dodgy, the fruits of which (it really does have to stop now) are on display, dotted among original comic strip art in the Maison Rouge.

The Maison Rouge is a foundation set up by collector Antoine de Galbert and it is, unlike many other contemporary art spaces its size, both huge and amenable, its central space the eponymous red house (really a house-shaped room) from which increasingly large exhibition spaces bloom outwards. The show benefits from this steady architectural unraveling, with its sense of graduated discovery. The eked-out pleasures of narrative—of being led, slowly, unwitting, into uncharted territories—marks the best comic strip art, which is really a system of tiny narrative allowances, like being fed a loaf of bread piece by piece. I spent quite a lot of time reading Windsor McKay’s pre-WWI Little Nemo in Slumberland, of which there are several hand-colored pages on display, marveling at McKay’s steady accumulations of elegant weirdnesses which culminate, always, in our hero falling out of bed and waking up. Or George Herriman’s original drawings for Krazy Kat, whose menagerie of eloquent and sadistic animals smashing cars and getting each other arrested is wilder and weirder even than their great fan, Philip Guston’s work. Or the peerless Hergé’s drawings for Tintin, one of which—a lovely pen and ink drawing on what looks like graph paper of Tintin descending via parachute through a black sky, clutching a petrified Snowy—reminded me, unexpectedly, of minimalist drawings (that parachute!). Seeing panels, laid out individually and planned to be whisked through in one Saturday afternoon, is a great delight. And how long did you last spend looking at a minimalist drawing?

I’ve been using words like “reading” and “original” to draw out the differences in reception between these works and the contemporary art they’re surrounded by, many of which (Warhol, Lichtenstein, Murakami) make great play of the refutation of both the original and the sequential, treating comic strips as the flotsam of modern culture, just another surface to be reheated and farmed out to an intern to make. But the pop project of comic-culling starts to look shallow and silly when placed alongside Herge, Herriman, and McKay (not to mention Schultz, McManus, and Outcault); in other words, when thought of as Bande Dessinée and not comic strips. At its worst, contemporary art’s mining of comic sources comes off as both smug and condescending, as in Hyungkoo Lee’s cynical (and plagiaristic) skeletons of Roadrunner and Felix the Cat, and the apparently endlessly viable strategy of making mannequins of out-of-shape superheroes. At its best—as in Jochen Gerner’s partly painted-over school map of Africa, with the names of countries and cities reduced to floating speech bubbles (“Go,” “Iq,” “Of”), or Raymond Pettibon‘s noir-ish one-liners—contemporary art picks up where the comics leave off, seeing them as a point of departure rather than merely signs to serve a vaguely political purpose (and yes, there are a lot of creepy Mickeys here).

What the show explores is the troubled notion of crossover in culture, which is always top-down, high to low, and never vice-versa (Picasso, Guston, Warhol, McCarthy, etc.), in which the bits and bobs of popular culture magically become worthy of note once ushered into the hallowed halls of highness. What’s left at the door, though, with your coat and bag, is pleasure. Twice I heard visitors laugh in galleries over the last few days: once at the Pompidou, while watching an Andrea Fraser video (in-the-know nasal snorts), and once at the Maison Rouge: a proper, guttural, rib-rattling guffaw coming from an elderly gent next to me at the Herrimans. Which would you prefer?