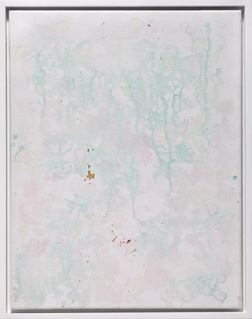

Dan Colen, "Untitled" (2008). Chewing gum and chewing gum residue on canvas in artist's frame. 19.1 x 15.1 inches. Courtesy David Nolan New York.

In his New York Times article on the opening of the Venice Biennale, Michael Kimmelman laments that the look of the exhibition “suggests a somewhat dull, deflated contemporary art world, professionalized to a fault, in search of a fresh consensus.”

Without reading too much into it, the critique that contemporary art has been “professionalized to a fault” feels analogous to the sentiment expressed by the anonymous graffito I mentioned in my previous post: “The only true artists are amateurs.”

Of course, the word “amateur” cuts both ways. In most contexts it connotes a lack of training, sophistication, or seriousness, but its derivation from the Latin amator implies that its foremost meaning is “lover.” Simply put, the amateur is someone who, motivated only by the love of the game, engages in an activity without expecting anything to come of it.

Two exhibitions that I encountered yesterday, Slough at David Nolan New York and Alice Neel: Selected Works at David Zwirner, brought this concept into focus in very different ways. Slough, astutely curated by the artist Steve DiBenedetto, is a group show with a complicated backstory based on the title word’s multiple meanings. As explained in the press release, the range includes “bog-like” and “primordial,” “moral degradation or spiritual dejection,” “cast aside or shed off,” and “the accumulation of dust on the rim of a fan, snow on the edge of a shovel, or trash in the breakdown lane of a highway.”

The show includes striking works by Dieter Roth, Jon Kessler, Robert Bordo, and Michael Scott, who represent quite a heterogeneity of aesthetic objectives and studio practice, but who are nonetheless united by a sense of improvisation, accident, and play: a what-if approach akin to kicking over a can of paint to see what happens next (which, in fact, is what Hermann Nitsch’s untitled canvas seems to be). Philip Taaffe’s swirls of pigment, titled Slough I and Slough IV (both 2003), and Andy Warhol’s invariably lovely Piss Paintings from 1978 adopt pure serendipity as their method and meaning; densely laden works by Larry Poons and the late Eugène Leroy revel in their raw materiality; Carroll Dunham’s surprisingly aggressive Untitled (1984-85), in graphite, ink and paint on wood veneer, bespeaks a jittery call-and-response that, like most of the strongest works in the show, seems to spring from an ethos of risk-taking oblivious to the ultimate salvageability of the results. Nothing is calculated, preconceived, strategized, theorized, or prejudged. The object comes into existence solely to delight its maker or, as it seems with Dan Colen’s chewing gum pictures, for the sheer giddy hell of it.

Alice Neel, "Young Woman" (c.1946). Oil on canvas. 32 x 25 inches. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York.

One Sunday last month I was sitting in Sara Delano Roosevelt Park in the heart of New York City’s Chinatown. A small ensemble of musicians were playing traditional instruments while neighborhood residents crowded the benches or milled about. An old man found the musicians’ wireless microphone and sang an apparently unsolicited solo. The tunes came one after another. No one clapped or even paid the instrumentalists much mind; for their part, the players seemed indifferent to whether anyone was listening or not. They were most likely amateurs, yet their musicianship was top-flight. The way the neighbors seemed to take them for granted, however, did not strike me as rude or condescending; instead, it evidenced how culture, rather than standing apart from the community, is woven into its fabric.

This is how I see the pictures of Alice Neel. Her paintings of lovers and friends seem part of a daily conversation, a record of who dropped by that day and had the time to sit. This feels especially true of the works in the first room of the David Zwirner exhibition, and of the nudes in a related show uptown at Zwirner & Wirth, all of which were done in the 1930s and 1940s. Neel was working in near-total professional obscurity, but this circumstance never diminished her drive to infuse these images with a solidity of form and a magnificence of color that bears comparison to the titans of European modernism. Her expectations for her work might have been humble, but not her aesthetic ambition, which she fulfilled through a searching eye, a sculptural line, and a savage palette. Her art was not her career, but her life. How many of us wouldn’t wish that for ourselves?

Pingback: Wishing Upon a Star: Dan Colen’s Escapist Fantasies | Nick Socrates Contemporary Art