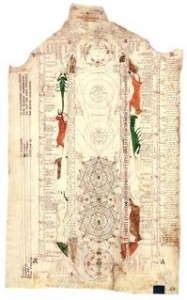

Opicinus de Canistris (1296–ca. 1354), Diagram with Zodiac Symbols, folio 24r, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City, Pal. Lat. 1993

Turning again to the oracular nature of art (see Monday’s post), it is compelling to consider that, in the Western canon, drawing as an autonomous art form first came into its own in the medieval period, embellishing the texts of the Bible and other works, both sacred and profane. If you believe, as I do, that drawing is the most direct route to the subconscious, this historical association implies a solid link between the psychological impetus of visionary art and the theological objectives harnessing its iconography. In other words, an id running wild might be reframed by its context, but it can never be tamed.

These thoughts were prompted by Pen and Parchment: Drawing in the Middle Ages at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which is easily (Francis Bacon: A Centenary Retrospective and The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984 notwithstanding) the most of-the-moment exhibition in the building. The overwhelming majority of works on display are presented in book form, rather than broken out of their original bindings. So it is hard to ignore their prima facie similarity to graphic novels and comic books, especially the simplified Matt Groening-style curves of the theatrical masks depicted in a mid-12th-century copy of Terence’s Six Comedies from Saint Albans, England.

The technical experimentation of these anonymous illustrators and scribes (often the same person), such as the variously colored contour lines in the Psychomachia and other texts written by Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, would feel as much at home in Pierogi 2000 as in Canterbury circa 1000. Not to mention the utter weirdness of the squat, schematic and anatomically inaccurate figures from the Salomon Glosseries, which were drawn in 1158 and 1165 in Prüfening, Germany. Or the text-free, comic book framing of a double-page spread from The Dialogues of the Holy Cross (1170-1180, Regensburg-Prüfening, Germany) and its detailed depictions of outrageous violence.

The most fascinating discovery of the show is the work of Opicinus de Canistris (1296-ca.1354), a priest and scribe for the Papal Curia in Avignon who, according to the wall text, “suffered from a stroke-like episode that rendered his right arm almost useless, yet he still managed to draw” and thereafter “worked obsessively to develop and convey his unique understanding of the divine order.” An actual visionary (“His illness, he felt, had brought him a vision from God…”), the large diagrammatic drawings selected from his portfolio of 52 works on 27 sheets of parchment (all made in Avignon between 1335 and 1350 and now held at the Vatican Library) bear a startling resemblance to modern outsider art. The drawings are built up rather than composed, with information overriding decoration as their primary motivation, which endows them with the same freakish, nonlinear narrative found in the most outré ‘zine art.

The crisp lines and sharp contrasts emblematic of both Opicinus de Canistris and comix artists like Eamon Espey return us to the kind of primal visual pleasure that drew us to illustrated books and comics when we were children. They also reestablish the intimate though often-denied connection between the verbal and the visual – a resetting of the dial to the image’s most basic form and function. The works on display in Pen and Parchment emerged at the turn of a millennium in the clearing between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance; graphic novels and ‘zines came into their own at the turn of a millennium after the rigors of modernism and the platitudes of postmodernism had both fallen apart. We are again back at zero, hallelujah.