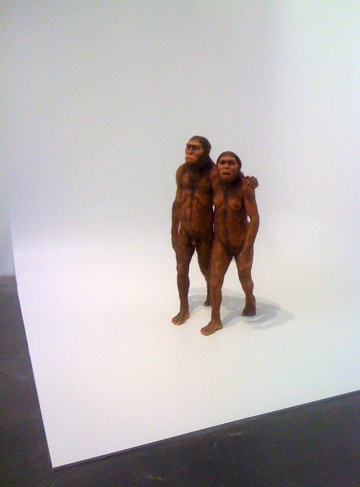

Tim Noble and Sue Webster, "Masters of the Universe," 1998–2000. Translucent resin, fiberglass, plastic, and human hair.

(continued from Part 1)

Down the stairs, Nathalie Djurberg’s sexually violent claymations are followed by Cady Noland’s sculptural image of Lee Harvey Oswald at his death. She has him riddled with holes, one in the place of his mouth and gagged with an American flag textile.

In the corner of floor three is one of the most iconic works in the show, Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Masters of the Universe (1998–2000). The pre-human couple have been installed on a extension rolling down from the museum’s white walls. It appears as if they’re stepping out of a time vacuum into a context vacuum to survey the room. From their vantagepoint, Pawel Althamer’s Schedule of the Crucifix (2005) is the work that demands the most attention, featuring a live performer posing on a cross ten feet up on the wall. He is stationary in a crown of thorns until his schedule dictates that he descend the ladder, change, and exit the room. Nearby, the figure in Andro Wekua’s Wait to Wait (2006) is seated in a motorized rocking chair upon a brick base and within colored glass. He wears clownish make-up and a dress shirt and, lacking pants, you see that this guy’s genitals have been effaced. Subtly in motion, he still seems disconcertingly real, particularly beside Althamer’s living sculpture.

There are odd consistencies between floors. Just about below the floor of Tauba Auerbach’s dimensionally expansive black and white dots are Nate Lowman’s silkscreen of the same ilk. Wrapped around the far side of the room, like Gober’s bed upstairs, is Maurizio Cattelan’s Now (2004), the wax body of JFK in an open casket—a more disquieting sense of sleep, to say the least.

Cattelan and Gober both are featured on the second floor with two more pieces reminiscent of slumber. Gober’s is a surreal, minimally furnished nursery wallpapered in flat illustrations of the road, woods, and sky from a driver’s perspective, repeated in variations and separated by clouds. There is a giant enamel sink resembling a urinal, two legs sticking out of opposite sides of the wall and, in the center, a simple wooden crib leaning diagonally at forty-five degrees. Cattelan’s room holds nine graceful body bags chiseled from marble.

Both artists share their spaces with an occupant staged by another artist. A female museum attendant standing facing the wall near Cattelan’s sculpture sings out from time to time, “This is propaganda, you know, you know,” before declaring the credo a piece by Tino Sehgal. The automated cadence of the attribution, delivered by such a warm and lovely speaker, reminds me of a memory I don’t have yet, of when people used to have voices. Another guard stands by silently in Gober’s room. The two change positions every couple minutes, both singing, but only one at a time and with Cattelan. (There are no lullabies in the nursery.)

It’s uplifting to see all these Top 40 artworks—many legitimately brilliant as well as catchy, including several I didn’t mention—gathered under the auspices of personal excitement, rather those of a more calculated, history-minded endeavor. In a sense, all the artists are sharing with Koons’s presence via his loud, imaginative vision of their work in concert. His sole contribution to the show, One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (1985), is comparatively subdued, at least in terms of its appearance. A basketball frozen in time and space, it can represent anything—body, planet, idea—suspended in an invisible substance and contained by a rigid structure. I’ll consider Skin Fruit as held in the transparency of Koons’s likes by the container of the museum. The question remains: how much here is transparent and how much just can’t be seen? How fun to guess!