Mr. Creosote, the morbidly obese character of the 1983 comedy Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, is a picture of gluttony never to be forgotten. Upon taking his seat in a fancy French restaurant, he begins to vomit, showing no concern for the people around him and the dreadfulness of his action. Throughout the skit he continues to project ridiculously large streams of matter onto the floor, into buckets, on the maître d’, cleaning woman, and himself. Between upchucks, he heedlessly orders and consumes copious amounts of food. In a darkly humorous ending, the character explodes, showering the restaurant and its patrons with human viscera. The camera pans back to Mr. Creosote, who is now a hollow carcass with a still-beating heart. The maître d’ presents him with the check.

The same year that audiences were introduced to Mr. Creosote, the art world was entering a period of phenomenal excess. The wealth enjoyed by upper and middle class Americans in the early 1980s brought about rapid growth in the art market. The resulting bubble would, like Mr. Creosote, eventually burst. At the present moment, we are acutely aware of this bulimic pattern: after the buying binge of recent years, the market (along with the larger economy) again purged, and given the latest art fair reports, is back on the rise. Might Mr. Creosote be the perfect metaphor for the contemporary art world that is always hungry for more?

Gluttony in art consumption and our craving for new things was at the center of a provocative panel discussion held earlier this month at The Independent art fair. As one of the seven deadly sins of Christianity, gluttony is of course loaded with notions of repulsive and immoral behavior. It suggests hedonism in food and drink while denying it to those less fortunate and in need. Of course, this idea is not universal. Gluttony can also be a sign of status, wealth, or desire unburdened by beliefs and moral principles. Panelists of “On Gluttony” expressed the full gamut of interpretations. Organized by Kreemart Salon (the group responsible for Haunch of Venison’s New York Cake Party), the program featured painter Will Cotton, food artist Jennifer Rubell, Rachel Lehmann of Lehmann Maupin Gallery, art advisor Raphael Castoriano, and art journalists Anthony Haden-Guest and Linda Yablonsky.

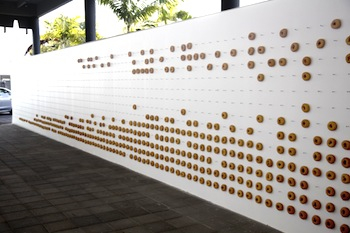

Jennifer Rubell, "Old Fashioned," 2009. Dimensions unknown. Photo: Elizabeth Jones / Eat Me Daily (via eatmedaily.com).

Jennifer Rubell — organizer of the now infamous gala dinner for Performa09 and the upcoming Brooklyn Ball — acknowledged that her work “looks a lot like gluttony,” a term with “an extreme moral component.” Yet morals around food are not what interest her as an artist. Rather, she is drawn to the aesthetic and psychological properties of food. Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, where sin and pleasure are inseparable, came to mind when she referred to her interactive food installations as “erotic engagement with plenty.” Her last big installation for Art Basel Miami Beach (an event known for surfeit) involved a great wall of Dunkin’ Donuts. Passersby were invited to indulge at will. In Rubell’s view, using food as medium is akin to collectors buying art: it is a means of extending the material’s life. By that token, gluttony is to make something (or someone) endure. Rubell argued that “there would be no art to filter down to the public trust” if it weren’t for the gluttonous nature of collectors. Meanwhile, Linda Yablonsky expressed concern over collectors and dealers who hoard, keeping all the work of a single artist in one place and away from the public. I sensed that others in the room (including myself) also found that idea nauseating.

Rachel Lehmann clearly wanted to shift the notion that overindulgence is inherently harmful. She spoke of the excess of information that defines our current moment and supposedly drives the pressure for artists to create more, bigger, and faster—collectors want new art to buy, museums new objects to show, and viewers new things to experience. (We all partake in the gluttony of the art world.) Lehmann seemed to suggest that gluttony of late has had its advantages. She reminded the audience that this is the first time in history that so many people are able to make a living as artists. That got a mild nod of agreement from Will Cotton.

Known for his pastry and candy-strewn dreamscapes, Cotton expressed that his own interest lay not so much in gluttony but desire and consumption that “doesn’t involve deprivation.” As an example, he showed an image of Pieter Bruegel’s Land of Cockayne (1567), in which three men lie prostrate, incapacitated by a visible wealth of food. The scene is based on a medieval mythical land of “extreme luxury,” where the severity of peasant life is unknown. Gluttony here, as in Cotton’s work, is to emphasize the pleasures of gratification rather than the grotesque. At the beginning of the discussion, moderator Jovana Stokic recited a quote from anthropologist Claude-Lévi Strauss, in which he addressed the gluttony of French society, saying, “every five years or so, it needs to stuff something new in its mouth.” To this, Cotton replied, “we should want more.” I believe he meant this in the best way possible.

The discussion was injected with a much needed dose of humor and cynicism when Anthony Hayden-Guest began projecting images of gluttony and greed from popular culture, such as Al Pacino in Scarface, having just pulled his face out of a mound of cocaine. (An interesting image choice, given the context and the drug’s association with art world affluence.) If you’ve seen Scarface, you know that protagonist Tony Montana’s unquenchable thirst for more led to his own end. Of course, the contemporary art world is not going anywhere. But while watching Montana self-destruct I, for one, thought the same poignant (though unanswerable) question Yablonsky asked: how much is enough?

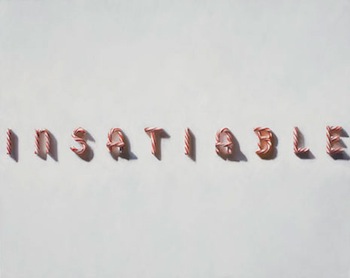

When the art market was hit by the current recession, critics cheered, arguing that the days of bombastic art and overindulgence were coming to an end, activating a shift in focus to art production (where it should be). I didn’t get a clear sense, from “On Gluttony” or this year’s art fairs, that things have changed to the degree that critics suggest. From where I sit, the contemporary art market continues to look a lot like the gluttonous, insatiable Mr. Creosote. As he said, somebody better get me a bucket.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: The Digest. 03.22.10. « C-MONSTER.net

Pingback: On Gluttony. Panel Discussion at Independent, New York | VernissageTV art tv

Pingback: Flash Points Wrap-Up: Art For Life | Art21 Blog