The territory of art that responds to, comments on, and intervenes in the art market is vast. There are a range of practices in contemporary art that involve currency as a literal medium (collage, sculpture, public performance, altered banknotes), but here I’m narrowing the field to consider a few individuals and local communities who create alternative currencies with the intent to circulate them as a medium of exchange.

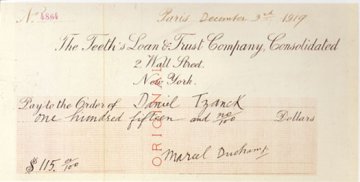

Artists have long been interested in currency design and reproduction, both as a technical challenge and as socioeconomic experiment. In the 19th century, American trompe l’oeil masters like John Haberle (1856–1933) and William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) painted depictions of U.S. currency to demonstrate their talents as photorealists. So successful at their craft, both were issued cease-and-desist orders by the Secret Service, who feared their next step would be counterfeiting. (It wasn’t, and they didn’t.) Marcel Duchamp, ever interested in authenticity and the value of ideas, created his first hand-drawn check in 1919 to pay his dentist, Daniel Tzanck. The “Tzanck Check” displays all the markers of a legitimate check, drawn by Duchamp to imitate official printing: the unique check number, the “Pay to the Order of” line, etc. Across the middle in red is the word “ORIGINAL,” which plays on the authenticity of the check as a legal promissory note but also speaks to this check’s status as a unique art object, signed by the artist. Art historian Katy Siegel notes in Art Works: Money (2004) that the signature is both the “ultimate proof of identity” and “a promise to pay — the essence of credit. The signature…assures the buyer that the aesthetic and social value created by the artist is contained within it.” Therein lay the Tzanck Check’s “real” worth. Years later, the story goes, Duchamp bought the check back from his dentist for a sum much greater than it’s face value of $115.

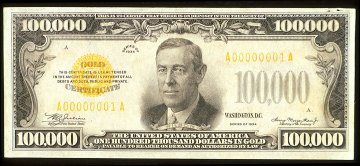

A similar relationship between market value and face value is played out in the work of J.S.G. Boggs (b. 1955), perhaps the most well-known “money artist,” who has been hand-drawing and spending his unique Boggs Notes since 1984. Like the trompe l’oeil painters before him, Boggs’s work is so convincing in detail that he has been threatened by the Secret Service for counterfeiting (he has been arrested in England and Australia), although his bills are typically illustrated only on one side, with his signature and thumbprint on the reverse. Each financial transaction is a unique performance; Boggs pays for goods and/or services with the face value of his bill, asking for any change in legal U.S. currency. He then sells that change, as well as information regarding the location of the Boggs Note, to collectors, who in turn enter into their own negotiation of value — generally paying many times the denomination. (The $100,000 notes shown above are used to pay his lawyers.)

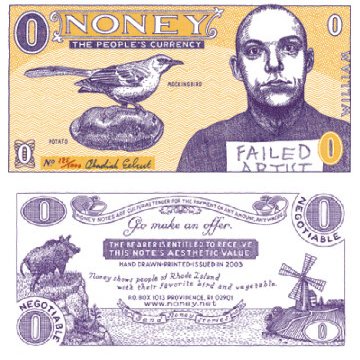

Unlike Boggs’s bills, which vary in denomination, the face value of Noney is zero. As the reverse states, “Noney notes are cultural tender for the payment of any amount, anywhere. Go make an offer.” Designed and printed in 2003 by Alec Thibodeau (under the anagrammatic name of Obadiah Eelcut) in Providence, Rhode Island, Noney’s first edition of 10,000 has circulated globally. Each screen-printed note is hand-numbered and hand-signed, and depicts on the face one of ten different residents of RI with their favorite bird and favorite vegetable.

The artist’s website includes an ongoing list of the goods and services that people have bought with Noney, ranging from the practical (“I traded a piece of it for two copies of a zine by a woman in Montreal about fictitious sexual encounters with each of the leaders of Canada’s four major political parties”) to the poetic (“I spent my noney on a design for a frisbee that has yet to be made”). Thibodeau himself has exchanged Noney for food, work by other artists and, in one instance, frequent flyer miles. Because these are an editioned multiple, the rules of the art market would ostensibly confer a lower value on Noney than on a unique work like an early Boggs note. But, Thibodeau argues, this is all relative anyway: “Noney returns a standard to currency notes. But instead of metal, tobacco or rum, Noney’s standard is the aesthetic value of the note itself. It’s an economic system backed by art — art that also serves as the system’s currency.”

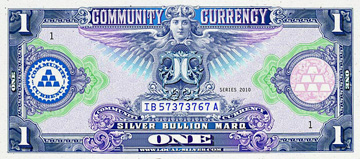

Stephen Barnwell, "Community Currency One Ounce Note," 2009. Digital print, 8.5" x 11". Source: www.moneyart.biz

As Thibodeau points out, the key to the success of alternative currencies is confidence: “Currency today is more abstract than ever. The concept of a guaranteed standard is gone. Money, whether in your pocket or your bank account, only has value because everyone believes it does.” This idea is at the heart of “community currencies,” which build local economies by maximizing circulation of trade within a defined region, and which are growing in number thanks to the plummeting confidence in the U.S. dollar. Some, like the long-established BerkShares in the Berkshire region of Massachusetts, are backed by area banks, who disburse the notes in exchange for U.S. dollars. Others are based on a time-exchange system, like the IthacaHours; both models require commitment and trust. Robert Swann and Susan Witt write in Local Currencies: Catalysts for Sustainable Regional Economies:

Confidence in a currency requires that it be redeemable for some locally available commodity or service…Local currencies can play a vital role in the development of stable, diversified regional economies, giving definition and identity to regions, encouraging face-to-face transactions between neighbors, and helping to revitalize local cultures. A local currency is not simply an economic tool; it is also a cultural tool.

Artists are central to local currency projects, both as designers and illustrators, but also because the barter system is already familiar territory; alternative currencies are in a way just a formalization of the art-for-services trade that has long ensured the survival of urban artists. The Brooklyn Torch, currently in development, was started by a group of seven artists in North Brooklyn to “bring together both artist communities and immigrant communities in our area to improve integration of social groups and economies as well as boost our pride.” With local businesses like Woodhall Hospital, which allows uninsured artists to trade their services for medical care through their Artist Access program, it seems a supportive culture is already in place.

Inspired by the growing number of these local currencies, and the potential for artist involvement, students in Jason Santa Maria’s “Designing Communication” class in the Interaction Design MFA program at the School of Visual Arts were assigned the task of designing a suite of five banknotes for one of several Manhattan neighborhoods. The parameters for the assignment parallel the kinds of concerns that communities discuss when embarking on a local currency project:

Create local currency for neighborhood in Manhattan. Research societal and political concerns for currency. What similar issues will you face for designing a local currency for just one neighborhood? Is something traditional called for, or something more modern? What’s important about your neighborhood? What’s important to its residents? How does color work as a system and affect the psychology of actually using money? Should it even be paper or coins? How could you convince a local community to use it instead of US Dollars? How does the form factor of the money affect usability?

Gene Lu‘s proposal for Alphabet City, called Alphabills, celebrates the neighborhood’s graffiti subculture in a sophisticated layering of references. Four denominations are mapped to specific avenues ($20 to Avenue D, and so on), and the fifth is the “40oz Pass,” in honor of “many of the first graffiti writers, b-boys, rappers, and DJs during the 1980s.” Laid side by side, the four notes form a stylized skyline, overlaid with the avenue letters in a typeface inspired by a storefront awning. On the obverse of each note is the work and tag of a different graffiti artist, which Lu imagines would be produced in limited runs to allow for more artists to participate. Lu’s Alphabills represent the best of information design, conveying a complex amount of information in a clear format that also evokes the cultural significance of a particular place.

Keeping alternative currencies in circulation requires a high level of interaction between you the bearer and your local purveyor, neighbor, or service provider. In today’s global and electronic financial system, built on credit, codes, numbers and data, artist and community-designed currencies keep the human element in the mix. That might be the most valuable commodity of all.

Pingback: Alternative Currency: Can Wynwood Benefit? Fauxpium