In 2006, Christopher Robbins, John Ewing, and Matey Odonkor came together to form Ghana Think Tank, a problem-creating project with the motto Developing the First World. Drawing from their experiences working in international development, the three were frustrated by the way that so-called solutions imposed by developed countries often completely disregarded the local wisdom of the communities they were meant to assist. Reversing the common directional flow, Ghana Think Tank invites communities such as Westport, Connecticut; Liverpool, UK; and Providence, Rhode Island to be on the receiving end of solutions provided by ad-hoc think tanks from places like Ghana, Cuba, El Salvador, or Serbia. In many ways, the subject of this work lies in the incommensurability of common sense and the complete failure of transposing one context onto another.

Recently, I visited Christopher Robbins at The Wassaic Project in upstate New York, where he is an artist-in-residence to ask him about the origins of and motivations behind Ghana Think Tank:

Erin Sickler: How did Ghana Think Tank come about?

Christopher Robbins: Well, it originally came from working in the Peace Corps and then from my experiences working and living in Fiji, West Africa, and Serbia. When I joined the Peace Corps in Benin, I was straight out of college. On the one hand, I was clueless. On the other, I could get a meeting with the mayor. I suddenly had all this power. My director at Peace Corps was very straightforward about the inherent cluelessness of my position. He said, “I don’t care if you grew up as a farmer in the States; you don’t know anything about farming here. They are going to call you an expert, because of the fact that you have a college degree, but you don’t know anything about how it works here. All you can do is give them your eager young American attitude and try to get people together.”

There was a lot of pressure on communities to accept what I (and larger aid organizations) was doing there. Conventional wisdom said that if you rejected a development package, then you would be considered a difficult community, and you could not get any more aid. So whatever I proposed, no matter how ridiculous it was, or even damaging, it tended to be accepted. I became very conscious, and cautious of this. After all, people had fought over the site of the new market in my village. They had physically assaulted each other. Another aid group built beautiful pigsties out of cement. In a place where, if you had money, you lived in a mud house covered in cement, and if you didn’t, you lived in a house made out of mud with no cement, no one was going to stick an animal in a solid cement and rebar house. But the chief said that if you put people in there — if you misuse the shelters — we would never get any more funding.

So they just sat empty.

I constantly saw instances such as these, where external solutions were being imposed on communities no matter how ridiculous.

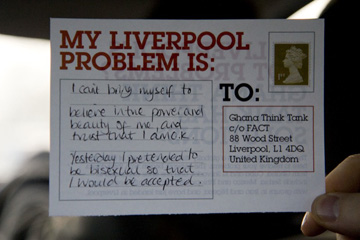

So, Ghana Think Tank came out of a pretty negative reaction to that, an effort to see what it was like to have external solutions imposed on my own culture. At this point, Ghana Think Tank was me, John Ewing, who had worked in Cuba and El Salvador – he had lived in El Salvador for a few years working for a political radio station — and Matey Odonkor, who is from Ghana [Odonkor is no longer with the group, which now includes Carmen Montoya along with the founders John Ewing and Christopher Robbins]. For the think tanks, we purposely picked people who were very isolated from development or art and then used the structure of international aid, but reversed the flow. Instead of imposing solutions in developing countries, we collect problems from the US and other developed countries and then seek solutions from think tanks located in the developing world.

Bollards: On Serbia's suggestion, parking blocks were installed on the sidewalks of Liverpool, while masquerading as official city workers

ES: Do you form the think tanks?

CR: Yes. They all come about from knowing someone we could enlist to help us. So in Ghana, there was this one guy who went to university in Accra, but lived in a smaller village. We asked him to put together some people in his village and then when he came back to Accra, get the problem from his email, print it out, or write it down and take it back to them.

ES: So they became a think tank within the scheme of the project? They don’t self identify as a think tank.

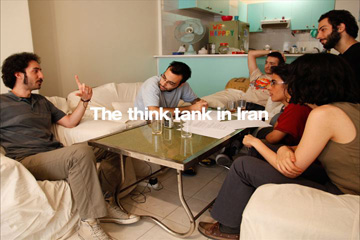

CR: No, nobody self identified as a think tank. For instance, in El Salvador everybody worked at this one radio station. In Cuba, it was a three-generation family. Iran was a group of artists called the Sazmanab Project. Originally we had enlisted a man who worked at the Alavi foundation, who knew about the Ghana Think Tank. He was going to bring the problems to several Iranian villages and run the think tank process with them. But then it turned out they sold half their building to a group that then rented it to a supposedly terrorist organization so all their assets were frozen, and the trip was called off. That was over a year ago, and they are still in court trying to get their assets released.

ES: What was Ghana Think Tank’s first project?

CR: Our first project was in Providence, RI. The first time we made up the problems ourselves. We wanted a mix of huge obvious ones and small ones, so we had “Obesity in America” and “PowerPoint Warps Our Mind” and then we had “Homelessness” and “I Can’t Dance.” This girl said, I can’t dance at parties, so the problems ranged from the very personal to the universal. After that first pilot, we have collected all our problems from strangers. We realized it was important to follow through on the solutions and do everything the think tanks said. For instance, one of the first solutions given for obesity and homelessness was to hire homeless people, dress them up in fat suits and have them perform social theater to obese people. We did not do that solution because we were too scared, so our first pilot was limited to cuter, easier, socially acceptable solutions, and I regret that.

ES: What think tank recommended that?

CR: That was El Salvador. The first time around, El Salvador gave social theater as the answer for everything. Need to get away from the computer screen, replace your PowerPoint with social theater. Need to cure obesity and homelessness: social theater. But from there on in, we promised to execute whatever solution was given.

ES: So you have to fulfill whatever the think tank proposes?

CR: Yes. And it’s made us extend the timeframe of our project. Our shows in galleries last about three months, and usually they pay us to be in town for ten days of that, so to make more than a photo opportunity we need more time. Now we are continuing to work with old problems, and extending existing solutions over longer periods of time. We are thinking of the Ghana Think Tank as a ten-year project right now, really extending the reach and scale. We want to form a non-profit and a commercial branch as well and explore all the potential of these ways of operating. One way is through art institutions, but we also want to explore these other systems as well.

Still Dirty, I-got-old: On Iran's suggestion, funny dirty memories were collected from the elderly community of Wales, and shared with younger generations

ES: Do you think it could be a viable business model?

CR: Yes, that is one of our goals right now. We want these ideas to infiltrate other parts of society. I have gotten some contacts from the corporate side and my wife is good on the NGO (Non Governmental Organization / International Development) side, so for the bigger picture I am pushing corporate and non-profit models. One thing that is important about the art side of it is that being an artist, you kind of work against yourself. If you are working with a material, you are always finding new ways to use it. You are always – not destroying – but kind of pushing and breaking how you are operating, extending how something works.

ES: You are a problem solver.

CR: Yes, but in a way that has to re-evaluate the problem once it is officially “solved.” And I think that approach, extended into any field, could be really helpful, even on Wall Street. I was trying to buy a house during the bubble. It became so apparent that the bubble was nonsense and I could not understand why everyone believed it. Yet, everyone else seemed to be making money off it. Now everyone has lost money, but the system still seems exactly the same. So that is to say that even as we go into the corporate or non-profit sector, the art part is important because it keeps you re-evaluating. Problem solving is one side of it—but you are always working against yourself.

ES: And questioning what you are doing and what are the ethics?

CR: Yes, it is self-reflective.

ES: There is a parallel to what you were saying about the development agencies in terms of artists doing socially collaborative projects with different types of communities where they basically parachute in, don’t really know the context, and are given a certain amount of time to realize a project. There is not a lot of opportunity for exploration. This happens a lot with biennials. There is a question of what is actually needed in those places and what wisdom is already there. It is not necessarily that those people don’t know how to solve their own problems; it is just that they don’t have the resources.

CR: Ultimately, development’s responsibility is to help people solve their own problems in a straightforward efficient and sustainable way. When our project starts dealing with problem solving, there is not the same responsibility. Which, on the cynical side means you could do a horrible development project and call it an art project but on the other, it does open up the potential of all these inefficiencies. I believe that “inefficiency” covers a lot of what is interesting and revealing in the world.

Dandelion: Remains of a dandelion replanting workshop at the Westport Art Center, as part of Mexico's solution for pesticide poisoning

This month, see Ghana Think Tank as part of the exhibition Re: Group: Beyond Models of Consensus at Eyebeam in New York. Alongside Ghana Think Tank, Christopher Robbins is working on a New Deal-inspired project, Works Projects Administration, one of a host of projects working in this vein including The Work Office, most recently at LMCC’s Swing Space, and the Work Progress Collective, this summer on Governor’s Island.

Pingback: christopher robbins blog » Blog Archive » Ghana Think Tank on Art21 Blog

Pingback: Interview: Christopher Robbins on Ghana ThinkTank | Provisions