Oak Park, Illinois is a very pretty and historically significant suburb that lies just outside of Chicago. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple is located here, along with a number of his Prairie-style residential homes. It’s the proverbial “great place to raise kids” kind of suburb, known for its racial diversity and progressive political leanings. Oak Park is also home to The Suburban, one of the premiere alternative art spaces in the Chicago area. Run by the artists Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam, who — along with being married with three kids — hold faculty positions at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the College of Du Page, respectively. The Suburban is a latter-day Mom and Pop venture (albeit a strictly no-profit one). It mixes sophisticated contemporary art presentations with backyard BBQs, baked goods, and laid-back conversation. There’s even a swing on the side yard for the kids. In the following interview, I asked Grabner about The Suburban’s history and her and Killam’s experiences running an art space in the midst of a bustling family life.

Claudine Ise: What is The Suburban?

Michelle Grabner: It is two small galleries on our residential suburban property that are given over to artists every seven to eight weeks.

CI: What made you and Brad want to start The Suburban, and why did you want to make it a part of (or, spatially speaking, adjacent to) your home?

MG: When we moved to Oak Park in 1997, the property we purchased had this odd little out-building attached to the garage. We initially used it as a garden shed, a place to park the lawn mower. Yet despite its diminutive size, we thought that it would be better served if we employed the building as an artist’s project space. It is important to say that this kind of thinking — bringing the contemporary art world to us — was not a new adventure. Before moving to Oak Park, we were living in Milwaukee, where we organized several exhibitions and enlisted artists and writers from around the globe to participate in our exploits. Why not invite Tracey Emins, Jan Tumlir, and Elmgreen + Dragset to participate in our projects? Their interest and participation encouraged us to work with artists we thought were compelling instead of convenient.

CI: Were there a lot of other domestic spaces in Chicago when you and Brad first moved here? What were the other models for this alternative mode of exhibition presentation that inspired you?

MG: The most infamous domestic space in Oak Park, and perhaps well beyond, is Frank Lloyd Wright’s early twentieth century home and studio on Chicago Avenue. Although an older model, it is progressive and influential all the same. There was Dogmatic, a first floor and basement space in a house in the Pilsen area of Chicago. It was a space we would frequent in the late 90s. Dogmatic was a great transitional space, a bridge between Chicago’s Uncomfortable Spaces of the mid-1990s to the current model of apartment spaces. Hermetic Gallery in Milwaukee was a lab for emerging artists and a think-tank for that city’s forward looking network of artists, poets, and musicians. Beyond the Midwest, we admired Frisenwal 120 in Cologne, Bliss in Pasadena, Thomas Solomon’s Garage in Los Angeles, Matts Gallery, BANK and City Racing in London, AC Project Room in New York, and All Girls in Berlin, to name a few.

CI: One of the things I love about your space is that a lot of the projects feel like they are still in process. Like the artist is still working out ideas but is far enough along to share what they’ve come up with publicly. What are some of the things you think about when you’re considering artists for upcoming programs?

MG: The primary consideration is that the artists we invite philosophically ‘get’ The Suburban. Ideally, they also appreciate its unique frame and understand that a project here is not propped up by the same set of conditions, resources, and goals as a commercial gallery or institutional space. So I guess it is not surprising that we know all of the artists prior to their visit to Oak Park and that they know us.

CI: Another aspect of your program that I really appreciate is that it often (usually?) features artists from outside of Chicago. Do you make a concerted effort to focus on artists from outside the immediate region?

MG: Yes indeed. As of the past few years, we stopped inviting Chicago-based artists. There is a bounty of divergent commercial, independent, and not-for-profit spaces in here dedicated to local artists. We are also totally uninterested in the regional rhetoric that so often drives (consumes) Chicago. We are simply more invested in the context of ideas.

CI: You have had some very well-known artists present work at The Suburban in the past. In fact, on The Suburban’s website there is even mention of Matthew Barney and Bjork having exhibited there! When and how did that happen?

MG: This gets asked regularly and I have to redirect you to the artist Nicholas Frank, who penned the essay that you are referring to on The Suburban‘s website. Nicholas’s essay is fiction with a wicked subtext. It is an outrageous “little engine that could” tale, examining the implications of a tiny gallery in the suburbs that can command the interest of powerful international artists. Ironically, the Suburban is often dismissed because of this. Or conversely, dismissed because it is small. Yet I would argue that it pulls back the curtain on the profound limitations and the artificial constructs shaping the venues that artists desire, possessing an element of institutional critique, I would unabashedly say. Ricky Swallow, Luc Tuymans, Katharina Grosse, Ceal Floyer, and over 160 other artists have made projects here but Barney and Bjork are still on the wait-list.

CI: What constitutes a successful show at The Suburban?

MG: …an artist who has learned something about his/her work by executing a project here.

CI: In prior interviews, you’ve always stressed that the Suburban takes place as part of a “working household.” I love that idea, but in my experience, a “working household” doesn’t always run smoothly. What are some of the ways in which you and Brad have integrated the work of the Suburban into other aspects of your family life?

MG: Don’t get me wrong, running The Suburban over the course of ten years and raising three kids in proximity to it requires an advanced form of organization that comes with its share of exhaustion.

Now that two of my kids are older, they begrudgingly help in wall painting, floor scrapping and other prep work between shows. When they were younger, we would often drag artists to the boys’ baseball games. When my son Oliver was in elementary school and it was time to select a foreign language, he said he wanted to learn the same language that that guy who was staying with us speaks. He was referring to the curator Jerome Sans, who speaks English with a thick French accent. Last month, my daughter Ceal (5 years old) and the two New York artists here for a project at The Suburban, Garth Weiser and Francesca DiMattio, dedicated an hour covering our sidewalk with goofy body tracings and chalk drawings. Ceal still asks when Garth and Francesca are coming back to her house. I guess with these few antidotes I am trying to convey that just having artists stay in your home every 6-7 weeks, year-in and year-out, over the course of a decade, has impacted each one of us in both fundamental and in cursory ways.

CI: Tell me about one of the Suburban’s most recent endeavors, the Great Poor Farm Experiment. What is its relationship to The Suburban? Is “the experiment” working? How will you determine its success/failure?

MG: The Poor Farm in northeastern Wisconsin seems like a natural extension of The Suburban. However, its physical structure and its geographical location are situated differently. The Poor Farm is a rural institution complete with 6000 square feet of exhibition space. The back half of the building is earmarked to become a residency. It, unlike The Suburban, carries non-profit status. We are gearing up for our second Great Poor Farm Experiment in August, a weekend of activities that compliment the straightforward year-long suite of solo projects and exhibitions inhabiting the Poor Farm galleries. I am not sure how to set the criteria for the Poor Farm at this point, besides knowing that I do not want it to be shaped by perpetual fundraising events, email blasts, etc. I just don’t believe that a quality non-profit space needs to behave that way. Or more to the point, we want to grow an extraordinary exhibition space in the middle of nowhere that doesn’t need those triggers.

CI: Outside of your home on the lawn, there are two headstones. One reads “Them” and the other reads “Us.” Tell me why you and Brad put them there, and what, if any, reaction you’ve received from your neighbors or passers by.

MG: This is a great question because it brings us back to Dogmatic, the former gallery in located in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. Those headstones you are referring to were made by the artist Gabe Fowler, who installed them in the basement of Dogmatic many years ago. When Gabe was planning to move to New York City, he asked if he could install them in our yard because he couldn’t feasibly take them with him. I said, “Yes.” They have been lodged under our Austrian pine tree for many years now and depending on who reads them, the meaning changes. I have talked to passers by and most tell me with conviction that it is a commentary on the Iraq War. I have talked to very few who view it as a polemic abstraction.

CI: How do you see the presence of The Suburban vis-a-vis Oak Park? Do your non-artist neighbors come to your openings and barbecues? Does it matter to you if they do?

MG: With perfect honestly, it doesn’t matter if our neighbors get it. However, many of them do get a general gist that something art-like is going on at that yellow house on the corner. That is enough understanding for most people and the specifics of the things they see are not necessary for a general Oak Park audience to be appreciative or amused. Oak Park is an educated and a progressive first ring Chicago suburb shaped by a load of liberal guilt and pockets of wealth. I do have welcome conversations with the junior high kids who trudge by while I am out gardening and who are not afraid to ask what is going on here. But I have no interest in doing outreach work for either The Suburban or The Poor Farm. I trust that people will find their way to us if they are sufficiently curious. And when they do, they have our full attention.

Pingback: Inside the Artist’s Studio: The Studio Reader and the SAIC Summer Studio | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Center Field: Interview with John Riepenhoff of The Green Gallery | Art21 Blog

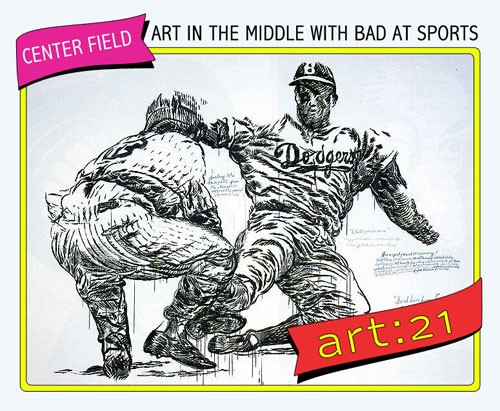

Pingback: Center Field: Art in the Middle with Bad at Sports | Top 10 Chicago Art Events in 2010 | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | A Good Wind: Forces of Nature in the New Age of Innocence | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Praxis Makes Perfect | A Good Wind: Forces of Nature in the New Age of Innocence | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide