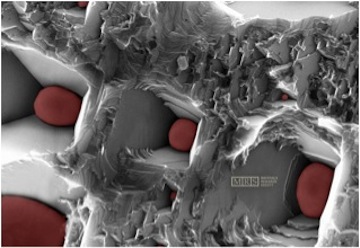

Waldemar Smirnov of the Fraunhofer Institut Angewandte Festkörperphysik, Germany, “Squaring the Circle,” 1st place winner of Materials Research Society “Science as Art” competition (2009). Image courtesy of MRS. Crystalline diamond grain anisotropically etched by spheres of molten nickel.

Popular opinion concerning the relationship between technology and the environment is of great interest to me; my own graduate research focused on its treatment in mid-century American children’s book illustration.

If you think about it, the junction between science and nature in fine art – that lovely gray area blending mechanical precision with mysticism and ambiguity – actually makes perfect sense in our current world. Contemporary art has always served as a solid podium for creative voices looking to hold a mirror to social conventions and lifestyles, to reflect the modern mind. Never have our lives been so dominated and guided by the progress of technological advancement; just note how most of us are fully armed with Steve Job’s arsenal of Apple products. We’re constantly plugged in, tuned in, streaming, uploading, and downloading, and tech offers ever-expanding platforms through which to express ideas and experiment with new ways of looking at our environment.

Perusing science and medical journals, one might think it surprising that the stunning high-definition images do not qualify as works of art. In fact, they do, at least to some, and the mounting interest in the art of such research has led to an array of contests founded to reward these aesthetic accomplishments – veritable art fairs for the scientific community. The Materials Research Society launched their Science as Art competition in 2005, offering prizes to winning entries on a biannual basis. The MRS website sums up the thinking behind such contests:

Occasionally, scientific images transcend their role as a medium for transmitting information, and contain the aesthetic qualities that transform them into objects of beauty and art.

Princeton University hosted a similar program, the Art of Science competition, in ‘05, ‘06, and ‘09; Caltech, Colorado State University, and Clemson University have followed suit as well. Tokyo-based optics and imaging corporation Nikon has its own version, the Small World Photomicrography Competition, which has been taking place for an impressive 30+ years.

Dr. Paul Appleton of the University of Dundee, UK, cell nuclei of the mouse colon (740x), 2-Photon fluorescence, 1st place winner of Nikon Small World Competition (2006). Image courtesy of Nikon.

These images evoke (perhaps ironically) an almost spiritual sense of awe, a powerful poetic reverence for the wonder of natural phenomena, one that is distinctly artistic in language. Is it science? Yes, of course. Is it nature? Yes – both in a literal sense, for those birthed from bioresearch and life sciences, as well as in the metaphysical manner in which they encourage us toward introspection, to consider our place in the universe. Is it art? Well … why not?

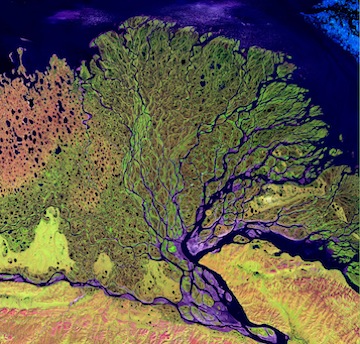

On the opposite end of the spectrum, other hybrid children of science-art love affairs cast the viewer in the role of god, granting us an omniscient bird’s-eye view of planet Earth. NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey jointly manage the Landsat Program, which utilizes digital photography of our coasts and continents to track the impact of man-made and natural forces across the globe. NASA and the GSFC Laboratory for Terrestrial Physics even maintain an “Earth as Art” online gallery, perhaps as a way to frame science as more accessible to the general public. Here, art is being effectively referenced as a sort of marketing and educational tool for disciplines largely viewed as devoid of the picturesque, sublime, or the romantic.

Lena Delta, Russia, Landsat 7 satellite (2000). Image courtesy of USGS National Center for EROS and NASA Landsat Project Science Office.

Established contemporary visual artists have seen this powerful imagery and run with it. Andreas Gursky and Florian Maier-Aichen – both Germans – have produced work that references satellite and aerial landscape photography. At once current and futuristic, surreal and familiar, nature seen through the lens of technology resonates deeply with us, perhaps because it allows us to don the hat of scientist and artist, both pioneers of the human potential whose very job entails crossing boundaries to explore new territory. Nature is, after all, composed of geometries, fractals, and mathematical relationships, and our own bodies are machines; it is no wonder we see the overlap as a distinctly artistic discourse.