1. What inspired you to start Primary Information?

I think there were two reasons to start Primary Information. James [Hoff] and I are both very interested in artists’ books and some of the publications we were most interested in were rare and expensive—too expensive for us. We wanted to share these projects with people that might not be able to afford them. The second reason is that we wanted to promote artists we were interested in outside of exhibitions which are limited to a time period and place. I’d discovered European artists whose work I’d never seen in person through books and wanted to do the same for American artists or younger artists.

2. Why is there a need for projects like Primary Information, which feature printings and collation of original art historical documents?

Much of the material we work with is forgotten or rare—perhaps having only been published once. We want people to have access to these projects without already being experts. I think artists used to write more and many younger artists aren’t encouraged to do so. By highlighting these writings or publications, hopefully it encourages younger artists to write about art.

3. Are there other projects, people, things that have inspired the Primary Information project? How does your work as a curator line-up with your work as the co-publisher of Primary Information?

We are very inspired by Seth Siegelaub, a curator, gallerist, and writer active in promoting conceptual artists in the 1960s and 70s. One of the things Siegelaub is known for is curating exhibitions which take the form of books.

4. What has been your favorite project to work on and why is this the case?

Right now the Lee Lozano Notebooks are my favorite because she made diverse bodies of work and the Notebooks are a great way to get insight into her process and how the works relate to each other. Publishing facsimile reprints can be an aesthetic challenge but I think the design retains the intimacy of the notebook form while still seeming current.

5. What projects do you see in the future for Primary Information? What direction would you like to take the press in?

The future involves more projects by younger artists that are developed specifically for the press in addition to the reprints that we do. We are also expanding our downloadable PDF section on our website starting with a collection of Siegelaub’s publications.

—

This past Friday, I got together with Miriam Katzeff who, along with James Hoff, publishes Primary Information, a publishing project devoted to making available printed matter of an art historic significance as well as supporting emergent artists books and other print-based artists’ projects.

What is immediately striking about all of the Primary Information books I’ve encountered is their simple yet exquisite design. What may not be so readily visible is the equally exquisite ethos that informs the publishing project. Many of us have had the experience where we encountered a treasured book or printed object in a used bookstore, but couldn’t purchase it because it was too expensive. Too often materials like the ones Primary Information republish become fetishized for their lack of availability. Through Primary Information, Katzeff and Hoff would like a readership, and younger artists and writers in particular, to be able to take a chance on printed editions because they like the design of a book or have found something compelling browsing the book’s contents. They would also like to put works back in circulation that they once could have only encountered from a distance—through poor reproductions, rumor, or exhibition.

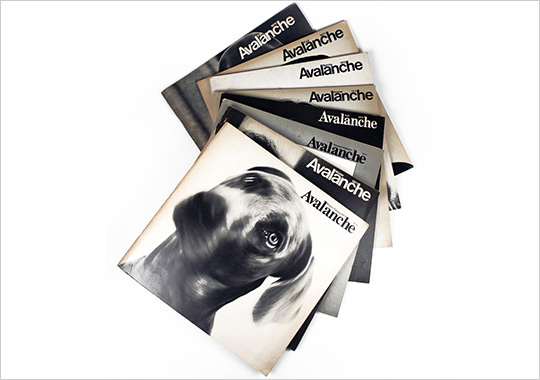

Another aspect of Primary Information’s ethos that I find compelling, is the publisher’s commitments to art writing that is not reducible to those formats which have become calcified in our era (the catalogue essay, review, email interview, or press release in particular), as well as to writing by artists. Against the various cynicisms of art critical discourse today (not least of which is a sense that art’s potential for critical engagement has become eclipsed by its market potential), Primary Information has published the Avalanche box-set, which includes staple-bound facsimile editions of the first eight issues of the magazine (from Fall 1970 through Summer/Fall 1973) published by Liza Béar and Willoughby Sharp, as well as a compilation of the Avalanche newspaper, which ran from May/June 1974 to the Summer 1976 in a series of thirteen issues.

Reading a few of the early Avalanches in Primary Information’s pristinely rendered facsimile editions, what struck me was the urgency of Sharp’s and Béar’s interviews with other artists, the high impact of Avalanche’s design, which combined gorgeous photo spreads with easy-to-read print content, and the playfulness of Sharp’s and Béar’s reports about what was current in the art world, located in the “Rumbles” section at the front of each issue of the magazine. The following, in fact, are two highly amusing rumbles concerning Andy Warhol’s and William Wegman’s at the time most recent projects (from Avalanche Fall 1970):

Although Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie (or Viva and Louis) is still tied up in litigation, he now has backing for his first Hollywood-based film, Specimen Days, the story of Walt Whitman’s experiences as a Civil War male nurse. With shooting set to begin in New Orleans, the regulars are ready but the lead is still to be cast. Allen Ginsberg, Mick Jagger, and John Lennon have all turned it down. (7)

William Wegman performed Three Speeds, Three Temperatures (right) this May in the faculty men’s room at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he taught last year. Since his participation in When Attitudes Becomes Form in Bern, Wegman has executed an unusual range of works including outdoor projects, floor arrangements, punning sculpture, body works, and a piece involving a sleeping girl and a dog. “They’re always asking me what my work stands for and I always tell them it doesn’t stand, it sits.” (8)

Another pleasure in reading Primary Information’s Avalanche facsimiles was to read interviews with artists before their “oeuvres” had cohered (or become saleable, for that matter). With few exceptions (such as the famous interview conducted by Béar with Dennis Oppenheim, Michael Heizer, and Robert Smithson in the Fall 1970 issue, where all three artists displayed a unique confidence in how their practices correlated), the artists interviewed in Avalanche tended to display a refreshing naivete—a sense that what they were exploring were new possibilities for art and for themselves personally.

In Avalanche and in the other projects Primary Information has published—such as Dan Graham’s writings on rock music and popular culture, Rock / Music Writings—one discovers artists speaking critically to one another’s projects and to a culture at large. Having taught younger artists in art school settings, I share Primary Information’s desire to educate and inspire younger artists to write publicly about each other’s work and to address their concerns as artists to a broader conversation about culture and politics.

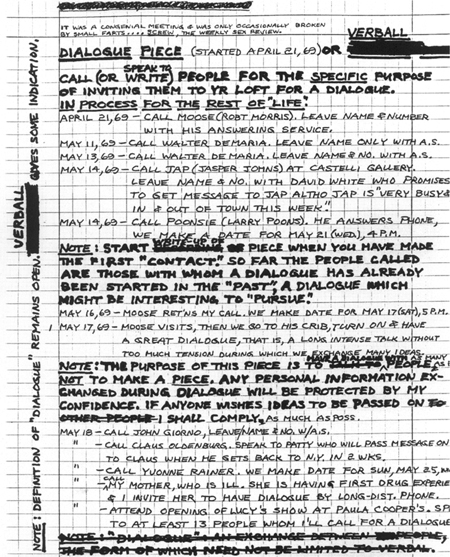

Another important aspect of Primary Information’s project is to provide documents of artists’ lesser-known works and phases of their career. Exemplary of this commitment is a facsimile of Lee Lozano’s 1967-1970 notebooks, where the artist records her movement away from signature forms such as her “wave” paintings towards time-based performance and group processes. Whereas typically a collection like Lozano’s Notebooks 1967-1970 would remain in cold storage indefinitely and thus only be accessible by scholars and archivists, Primary Information has made available a facsimile edition of the notebooks which displays the fascinating processes of an artist struggling through aesthetic problems that would eventually lead to Lozano’s renunciation of her practice as a visual artist.

The drama of the notebook—and the immediacy of certain marks, erasures, rewrites—cannot be overemphasized, as though the notebook were a kind of feedback device working in tandem with the performance works themselves. By the end of the notebook, the reader is in a much different place from where he/she began with Lozano’s sketches and mathematical formulas for the wave paintings. We are before her renunciation. I am not sure if this drama could be displayed merely in a transcript form, or through a scholar’s rendering sans visual documents. Regardless, there is a lot to be said for making the aural experience of the notebooks available to a readership, and one specifically who may be encountering Lozano’s work for the first time.

Is the publisher a curator? The term “curator” is obviously pretty played-out at this point, but I think it is interesting that Katzeff works as a curator with Team Gallery, and that her employment may inform her work with Primary Information. Inasmuch as book publishing and curation both shape attention—and specifically one’s attention to particular cultural-historical currents and continuums—Primary Information conflates the activity of publishing with curating, the archivist’s labor with a vigorous and compelling design practice.

A project which highlights correspondences between curator and book designer/publisher is Primary Information’s upcoming “fanzine” publication Mirror Me, edited by writer and curator Brandon Stosuy with German artist Kai Althoff, after a suite of events the pair organized during the summer of 2009 at Dispatch Bureau on the Lower East Side. Thanks to Katzeff, I was able to preview a PDF of Mirror Me, which combines the scrappy, high impact design aesthetic of ‘zine culture with the occult content of Black Metal music and art. Among the materials gathered in Mirror Me are photographs taken by the editors and others involved with the project, documents from the Mirror Me events at Dispatch Bureau, and various poems and scraps of prose of a mystical and inspired import. One of my favorites among these scraps describes an encounter between Kai, Brandon, and Varg Vikernes of the Norwegian Black Metal band, Mayhem:

They tell us Varg Vikernes is almost free. He killed someone in the early 1990s. At that time he believed in Satan.

And Brandon was relieved, and so was Kai, when they heard Varg was to be set free after all these years. While in prison, he taught so many about paganism. He is a paganist and a racist, therefore he will also not accept homosexuality. They are eagerly expecting his steps into a life of paganism, devoid of the limitation of being imprisoned.

Wynton Marsalis writes the most refined music, and he plays the trumpet. He did soundtracks for Spike Lee to multiply all New York summers known in the year of 1985. This is amongst a black community.

Brandon admires Varg’s music. Kai wants to follow Varg and wonders how it all goes together with Brandon wanting the country to be governed by Barack Obama, while also listening to Varg.

And Kai thinks Varg Vikernes would be a man he truly wanted to follow,denying his false conception to love a man in the W R O N G way, which will automatically lead to his self-perception as scum in the eye of Varg. Thus, if told to be executed, he would accept with no lament. Wynton Marsalis stands for culture and smartness. And self-confidence.

Wynton is what stands for the civilized in man. He is looked upon as the most degenerated form of a black man by some pagan, as this blackman holds the power of awareness and intellectualism.

This is questioned. Also by some semi-forceful act.

With Mirror Me and other upcoming projects, Primary Information moves in a slightly different direction from their previous works, from the past into the future. If Primary Information’s former projects represent a mode of recovery and transmission (to archive, document, redistribute) necessitated by our current cultural moment, then these new works make visible community-oriented art discourses as they are emergent, developing, and future directed.

Primary Information, amidst a widespread proliferation of projects by contemporary artists, publishers, educators, scholars, and curators dedicated to reexamining late-20th century art histories and presencing visual art discourse in the early 21st century, provides an attractive model for placing current cultural production within critical historical frameworks. By making available printed matter in relatively inexpensive facsimile forms which respect the documentary integrity of the original object and collating uncopyrighted materials (such as those of the Art Workers Coalition) in PDF formats, Katzeff and Hoff provide an invaluable resource for contemporary artists, scholars, students, and fans of previously submerged art-cultural histories.

Pingback: Picasso’s Portraits of Dealers, a Giant 4′33″, etc[Collected] | 16 Miles of String: Andrew Russeth on Contemporary Art and Art History | ARTINFO.com

Pingback: manystuff.org — Graphic Design daily selection » Blog Archive » MIRROR | ME

Pingback: ICA: A Painting with a Purpose: Sarah Crowner and Primary Information at ICA « Miranda