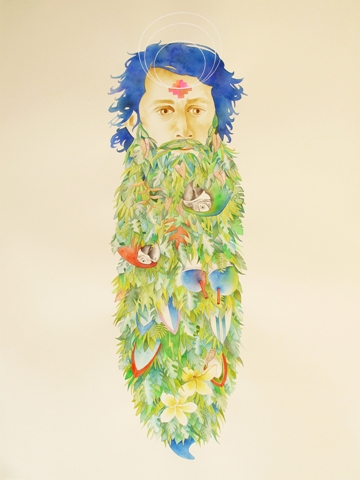

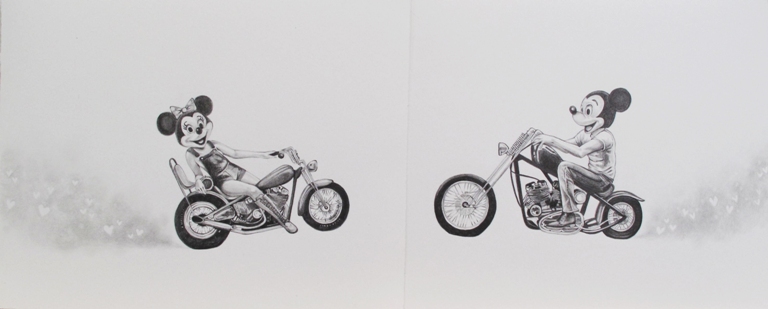

Gina Tuzzi, "Love Will Never Do Without You (for Brian Wilson)," 2010. Acrylic and graphite on board. Courtesy the artist.

Nostalgia is the longing for a home that never was; its subject is an idealized place where the troubles of today hold no sway. In paintings, drawings, and sculptures, Northern California artist Gina Tuzzi expresses her nostalgia for California in the 1970s, the era immediately preceding her birth. Mining this imagined past for clues to the present and future, Tuzzi turns to record-album art, family photo albums, and her memories of growing up in Santa Cruz, a California beach town where the spirit of the 1960s and ’70s arguably lives on.

Here, I talk to the artist about a resurgence in hippie culture and imagery in Bay Area art, her love of Neil Young, and how art school convinced her that “nostalgia” was a bad word.

Victoria Gannon: Why is 1970s culture and imagery so important in your work?

Gina Tuzzi: My parents moved to the coast in 1975 from the Central Valley and immediately got heavily involved in van and Harley culture, and founded Santa Cruz Vans in 1975. I grew up on the west side of Santa Cruz during the ’80s, when competitive surfing was huge. My parents would go on these van runs with hundreds and hundreds of people who were living in these custom vans. So this idea of nomadic living was very much what I understood Californians did when they turned twenty. This was my idea of what I was going to do; I was going to go on this big van adventure, because that’s what my parents did. I think that’s where a lot of this comes from.

That’s one of the reasons this whole ’60s and ’70s counterculture trend is so fascinating to me, because I’ve always been interested in that time period.

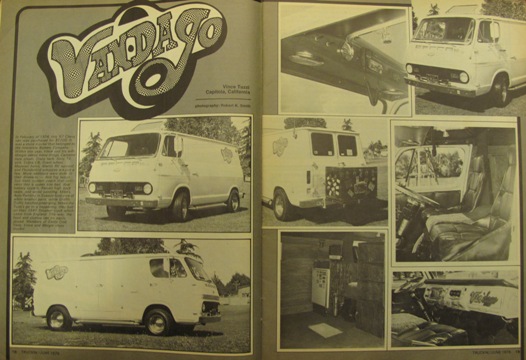

Photo spread of artist's parents' van. Featured in "Truckin' Magazine," June 1976. Courtesy the artist.

VG: What kind of art are you seeing that reflects this trend? I keep seeing pyramids and triangles.

GT: The trend I see is this dreamy communication with the past. There are a lot of shaggy gypsy installations going on. Found relics, driftwood lean-tos with coral-colored silk hawk feathers. You wonder, “is this a place to have a ceremony?”

VG: It’s quasi–Native American. I feel like that’s a trend I keep seeing.

Example of sacred geometry. Photo courtesy Sarjana Sky.

GT: I both love it and hate it. Seeing it over and over again, it starts to wear down. I think with certain things, like all the geometric shapes in work—sacred geometry’s showing up a lot—I think it goes back to people wanting to believe in something. There’s this big trend, globally, of reconnecting with Mother Earth and trying to take care of her, and I think we’re trying to go back to the knowledge of the ancients and the wisdom of other cultures. We’re reaching out to communities that are involved with their relationship with the earth, because we’ve created such a disconnect with the earth; this is our way of trying to get back to it.

VG: But all this imagery feels like such a superficial way to do it.

GT: I feel you there.

VG: I had my whole hippie phase in high school where I truly thought I was a hippie; it was ridiculous, because I embraced the imagery and the fashion and really didn’t have any beliefs at all; it was this very superficial embrace of the culture. I remember being totally caught up in the romanticism, and this quasi-mystical element to it. That’s what I see when I look at a lot of work right now.

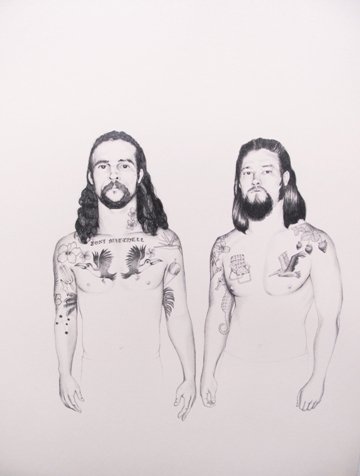

Mark Warren Jacques and Seth Neefus, "Free Life Center," from an exhibition at Needles and Pens in San Francisco, August 2010. Photo courtesy of Needles and Pens.

So when did you realize you weren’t necessarily going to go on a big van adventure? Was there a moment when you realized there were other things you could do?

GT: In probably mid- to late adolescence, I started to realize I could move out of Santa Cruz—there’s life outside of Santa Cruz.

I moved to rural Northern California, northern Humboldt County, and went to school up there. I went from one insulated bubble to an even smaller insulated bubble and had all these other experiences and then started to reflect back on these things. I think it was always with me, but it took living in another coastal California community to get a sense of how different those tribes were, and how provocative I thought all the visuals within that were.

Gina Tuzzi, "Without You," 2010. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.

VG: Can you describe the differences? I haven’t spent time in Arcata or Humboldt County, but I don’t think of it as being different from Santa Cruz.

GT: They’re so different. In Santa Cruz, until 1989 when the Loma Prieta earthquake annihilated the downtown, it was a really bohemian, free-spirited, freaky, and fun town. Then in the process of rebuilding after the earthquake, and then the dot com boom, all this money came into Santa Cruz, and they built over this bohemian paradise. That’s how it felt to me, in my youth. I was seven when Loma Prieta happened, so I don’t have a critical definition of what the community was like. In my dreamlike memories of it, it became super commercialized, and there were tons of mansions being built everywhere. I wanted to get away from that, so I went to school in Arcata and ended up living there after graduating.

Arcata, first and foremost, is a college town, but it’s a town based on pot growing. Logging is the ghost of the north coast; it’s practically not there at all anymore. Lots of little towns were established on logging, but that commerce isn’t there, and they’re ghost towns that have been supplemented by the marijuana industry. It’s a cash industry, an underground industry, fundamentally illegal.

VG: In California, you bump up against that underground world. It’s inevitable. It’s very secretive, but you all know what’s happening. Physically and culturally, it takes up a lot of space in California, but nobody is able to acknowledge it or look straight at it.

A lot of the imagery and culture of the 1960s and ’70s was about seeking and finding a state of bliss. I see that in your work.

Gina Tuzzi, "El Dorado (1989)," 2009. Acrylic on paper. Courtesy the artist.

GT: I’m definitely using lots of paradise imagery to express that vein of desire and longing that I’m trying to talk about. I love using star imagery, because it has that great history of navigation, but it is so oddly cryptic and endless and infinite. I use lighters a lot. In one painting, I have a hand holding a joint, and a hand holding a lighter. I love the idea of you and me getting together and having the components to feel intoxicated—literally, and also that the combination of you and me can be intoxicating. I’ve always thought that “you and me” was the most erotic combination of words.

It’s hard to say what’s at the core of all my work; I want to say me, but I also want to say it’s my relationship to Top 40 rock ’n’ roll records from the ’60s,’70s, and ’80s. Growing up, I had things that were my rituals, and one of them was listening to my parents’ entire record collection. They had this extensive vinyl collection. That was my introduction to poetry and talking about my feelings and constructing these ideas of love and revolution.

VG: You use a lot of song lyrics and song titles in your paintings.

GT: I do. I was in my studio with a friend the other day, and he said, “You could say that you’re ripping them off, or you could say that you’re covering those songs, in a different way, doing a recontextualized cover of a pre-existing song.”

I thought that was amazing and such a nice alternative to ripping them off. I hate to think of it as that. I think of it as creating a dialogue with someone I could never actually have a dialogue with.

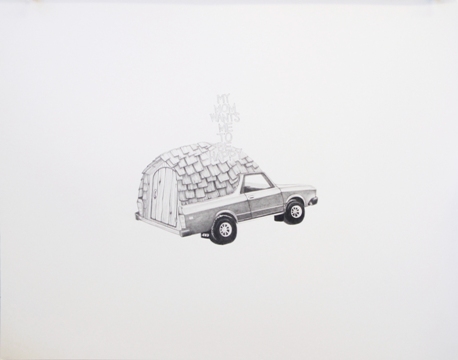

Gina Tuzzi, "Broken Arrow," 2009. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.

VG: Especially with the Neil Young song titles — those songs carry such weight, like “Comes a Time.” Reading the song title gave the image a different context. It made me think of the ways that song has been a soundtrack to different people’s lives. I remember listening to Neil Young my first year of college at UC Santa Cruz, and listening to “Comes a Time” and “Sugar Mountain” and thinking, this is about me; this is about this moment in my life. I’m sure a lot of people had that same reference point. When I saw your drawing, Comes a Time, which is about transitions and turning points, it brought it all together. What’s the particular significance of Neil Young?

GT: I was listening to a ton of Neil Young when I first moved into my studio at Mills. He has this one song, track one off of After the Gold Rush. I completely misinterpreted the lyrics. He says, “Is it hard to make arrangements for yourself when you’re old enough to repay but young enough to sell?” But I heard “repaint,” instead of “repay.” I thought to myself, He’s thinking about himself like he’s a used car; that’s brilliant. I had been thinking of myself as a house, and thinking of my paintings as a house. And I thought, Neil thinks of himself like a car, and I was thinking how beautiful it would be to build these houses on these cars—what a perfect marriage. That was my connection with Neil—it took off from there.

Gina Tuzzi, mixed media. Courtesy the artist

VG: How were you thinking of yourself as a house?

GT: When I was living with my parents for a few months before graduate school, I built this shack in the backyard as my studio. I was thinking of this structure as mine, and that structure as theirs. Then I was thinking about Arcata and how all these homes are growing these illegal gardens on the inside; I thought that was a beautiful allegory for growing things inside yourself that you don’t want to share with people. These houses are like shut-down, closed off people. I was trying to work with that metaphor for awhile, and then the Neil Young thing happened, and I misheard those lyrics and united the homes on the backs of the trucks. That turned into a whole other thing.

VG: Has he always been important to you?

GT: Yeah, most definitely. Forever and ever, since I can remember.

VG: Why do you think him in particular? His music?

GT: It has a lot to do with his relationship to living California. I’ve always connected with that. Neil Young was a massive trend about two years ago. There was this big Neil Young-related show in Chicago and a Modern Painters article around the same time.

VG: Was it the ’70s version of Neil Young? Or today’s?

GT: It was the ’70s Neil Young. I think his popularity is a byproduct of this sort of retro ’70s trend that’s happening.

VG: Do you think of your work as being nostalgic?

GT: That’s one of those terms that I feel like my art-school education taught me to think is a really negative thing. But yeah, I do. I totally do think it’s nostalgic. It’s yearning for something that happened a million years ago.

When I do recognize that element of nostalgia in my work, I always think it’s my not being willing to participate in the present, wanting to participate in something that’s not only in the past, but so distant in the past that it doesn’t involve my existence. It’s my sense of escape. I don’t want to deal with the present, so I deal with something I don’t even understand. This new body of work is dealing with the future; it’s a projection of things I want to happen in my lifetime. When I realized that, I thought, I’m not being present in any of this. It’s not about what’s happening right now, it’s about what’s happening in 1976 and what’s going to happen in 2014.

Gina Tuzzi, "Accident," 2010. Graphite on paper. Courtesy the artist.

But I didn’t grow up in a house that went to museums or had art books or art education. I would get lost in album covers, and that was my reference to graphic culture or 2-D culture. It came through Surfer magazine and my parents’ vinyl collection, so much so that, twenty-seven years later, that’s what I’m still interested in.