Ten memorable art-related moments of 2010, in no particular order:

10. Best animal weirdness: William Pope.L, Small Cup, 2008, Video, 12:52 minutes, included in the 2010 DeCordova Biennial

Filmed in one of the old textile mills that dominate the central Maine city of Lewiston, where the artist teaches in Bates College’s Department of Theater and Rhetoric, Small Cup is a layered commentary on architectural symbols of power. Set in the center of the cavernous mill is a small-scale Italianate cupola (a “small cup”) that is gradually overtaken by a group of curious goats and chickens, who feed, lay and crush eggs, and defecate inside it, butting and scratching until the dome falls. Score one for the animal house – carnivalesque, disturbing and triumphant.

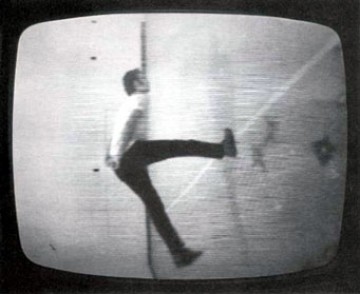

9. Simplest expression of a complex thought (or vice versa): Bruce Nauman, Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk), 1968, in the 2010 apexArt exhibition You Can’t Get There from Here but You Can Get Here from There, curated by Courtenay Finn

Nauman’s laborious and exaggerated walk, shot with a fixed camera on its side over the course of an hour, embodies the eccentricities of Samuel Beckett’s Watt. Awkward, exhausting, and ultimately mesmerizing, Slow Angle Walk perfectly illustrated the paradoxical complexity of this exhibition’s theme: the relationship between reader and text, the fictional and the real.

8. And on a similar note…Fred Sandback. I’m a sucker for Minimalism, so I’ve been happy to find him everywhere all of a sudden. ColorForms, at the Hirshhorn Museum last spring; prints and drawings in the Worcester Art Museum’s Minimalism: Logic and Structure, and the recently-opened Fred Sandback: Sculpture and Works on Paper at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College. With nothing more than stretched lengths of yarn or spare, ruled lines, Sandback managed to convey form, alter space, and shift perception.

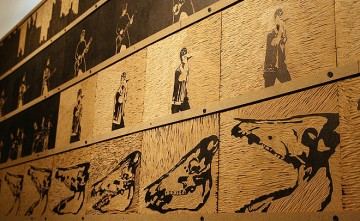

7. Best city-wide collaboration: Philagrafika

In scope, ambition, and execution, Philagrafika 2010 was a success both for the city of Philadelphia and for printmaking as an art form. Some of the most exciting work found connections between the seriality inherent in multiples and in video, as in Tromarama (above) and Christiane Baumgartner, both at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

6. Best old-school genius: Gerhard Richter, Lines Which Do Not Exist, at the Drawing Center. Every once in a while you need to dust off the G word, and Richter’s five-decade survey of work on paper deserved it. Rather than present any conclusions or highlight a chronological progression, the exhibition instead served to showcase his incredible range of expression in a variety of media, approaches, subject, and scale. I’m sorry I only caught it once.

5. Best use of rubber stamps: Case Conover, Everything Tree, 2009 at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art 2010 Biennial. Conover’s print made innovative use of this DIYers favorite. The bottom three-quarters of the sheet are covered with layers of stamps, individually recognizable at first (globes, letters, piano keys, houses), then gradually becoming more dense until the blackest layer forms the ground line, out of which sprouts a single tree. Cross-section of a comic-book landfill or a serious Shel Silverstein-style meditation on what supports our ecosystem? Both? Either way, Conover has a steady hand.

4. Best incidence of live arthropods in an exhibition: Roni Horn’s Ant Farm, 1974/2007, in Roni Horn AKA Roni Horn, ICA Boston (organized by the Whitney in association with Tate Modern)

At first this piece seemed like an anomaly in Horn’s thirty-year survey, but after watching the ants do their busy thing for awhile it started to come together. Horn’s work deals with mutability – of language, memory, the elements – frozen in state, as in the cracks and tiny bubbles suspended in glass block sculptures; in close-range portraits taken over a span of time; or in photographs of the water’s surface. Ant Farm prompts the same close observation, and presents a similar elision of surface and depth, but with the obvious difference that here change is no longer implied, but active. Plus it was a bit of a thrill to learn that they were fed mealworms and sugar water every couple of days through small holes in the frame – I loved the image of someone supporting the ants as they built their own little world.

3. Best divine inspiration: James Hampton, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly, ca. 1950-1964, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Hampton, a D.C. janitor and self-titled “Director for Special Projects for the State of Eternity,” built this massive altar out of found materials while working in seclusion, guided by visions and voices, for fourteen years. The result is a monument not only to God but to passion and singular commitment (and, it should be said, shiny things). Heralded by the Smithsonian as America’s greatest work of “visionary” art, the altar is displayed in the folk art galleries, while upstairs in the vaulted marble contemporary wing hangs Pepón Osorio’s El Chandelier, 1988. Similarly built from toys and trinkets, Osorio’s work makes a wry comment on abundance and the illusion of wealth, while celebrating the kind of resourcefulness Howard embodied. Irony, intention, culture, and formal training separate these artists, but the magpie aesthetic they share speaks volumes about kitsch and the perception of class – volumes best left for another post!

2. Best big-museum show: The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture 1839 to Today, MoMA. Smart, comprehensive, and illuminating, The Original Copy presented hundreds of photographs that are at once incredible works of art in their own right as well as important documents of practice, process, and performance.

1. Best reality check: Children’s Museum of the Arts, Manhattan

I fell in love with this place as soon as I walked in. The space is small and a little crowded, but the kids are too absorbed to notice. There’s a great range of open-ended activities, and the staff – I’m guessing mostly local art students – are friendly and patient. Borrow a kid if you don’t have one and go remind yourself what it’s all about.