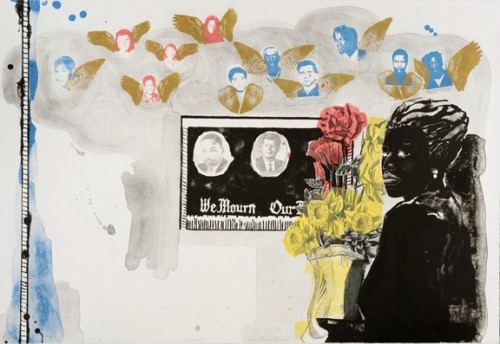

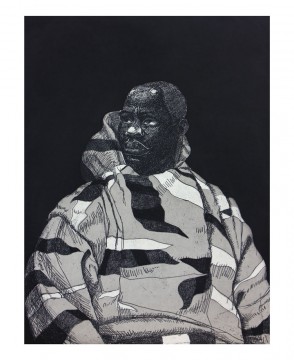

Kerry James Marshall. "Memento," 1996. Color lithograph with gold powder on soft white Somerset. 30 x 44 in. Edition of 33, Printed and published by Tamarind Institute, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In celebration of National African American History month, this issue of Ink is focused on selected prints by Art21 artists that react to and re-interpret African-American history. Ellen Gallagher, Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, and Fred Wilson are deeply engaged with this topic in all of their chosen media, including prints, bringing past events and practices to the forefront in order to provoke thought on the present and future state of race relations and Black identity in this country.

Ellen Gallagher’s groundbreaking DeLuxe portfolio (a detail of which is the signature image for this blog, below), 2004-2005, remains one of the most sensational and influential editioned works to have been published in the past decade. The portfolio, a series of 60 multimedia prints in an edition of 20, is part of a larger body of work in which she re-purposed and transformed advertisements for beauty products and vocational schools aimed at African-Americans (primarily women) from vintage magazines, cutting out the eyes, hair, and other details of the models and replacing selected areas with collaged elements, then arranged the results into dizzying grid patterns that consume the viewer’s field of vision. This series of unique and editioned works had a deep impact on the cultural landscape and instigated renewed dialogue on race issues and ideals of beauty. In addition, the DeLuxe prints were a great feat of technical achievement.

Many of Gallagher’s works from this period heavily incorporate or focus entirely on wig advertisements, and DeLuxe includes several such images. Commenting on her “wig ladies” in the April 2004 issue of Artforum, the artist reflected:

the wigs admit an anxiety about identity and loss: they map integration, the civil rights movement right through to Vietnam and women’s rights…These women are not just trying to be beautiful: they had to have these prosthetics. It’s about what you needed to go out the door, like you weren’t even reasonable until you put these on.

Gallagher has also examined the use of exaggerated eyes and lips in racial caricatures, isolating and repeating them endlessly in a kind of visual babble that underscores their absurdity. She thoroughly explored this idea in her first portfolio of prints, Ssblak!Ssblak!!Ssblakallblak! Wonder #9, 2000.

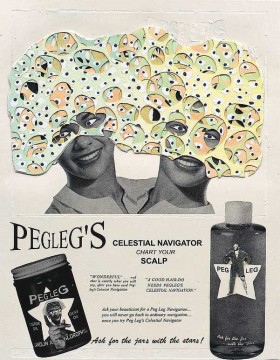

Ellen Gallagher. "Millie Christine" from “DeLuxe,” 2004-05. Aquatint, photogravure, laser-cutting, oil, graphite, collage, pomade, 13 x 10 inches, Edition of 20. Photo by D. James Dee. Courtesy Two Palms Press, New York. © Ellen Gallagher.

Millie Christine, one plate from the DeLuxe portfolio, brings together many of Gallagher’s motifs from this period. In addition to the bug eyes and bouffant wigs, which here meld the women together into an absurd monster-like form, the peg leg – a frequent reference in her work of this period – appears here. Gallagher has spoken of the peg leg as a signifier of two ideas: Captain Ahab in Melville’s Moby-Dick, and the famed tap dancer Peg Leg Bates. The Moby-Dick reference hearkens back to her 2001 Gagosian show titled Blubber – an exhibition of large texturized and water-like canvases that suggested the racial subtext embedded in the 1851 novel: ocean travel and the Middle Passage, white aggression, hypocrisy, all-consuming bitterness. Whaling’s metaphorical resonance with the slave trade and its ramifications has continued to be important in Gallagher’s more recent video and unique works on canvas and paper. Her current work, which the artist describes as a “desire to create an expansive, fluid realm that is both the concrete historical fragments it is made up of and the new form it describes” is currently on view at the Gagosian Gallery, Chelsea, through February 26.

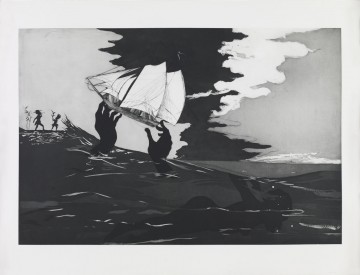

Kara Walker, "no world," 2010. Etching with aquatint, sugar-lift, spit-bite and dry-point on Hahnemuhle Copperplate Bright White 300gsm paper. 27 x 38 inches. Edition of XXV. Printed by Burnet Editions, New York. Published by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. © Kara Walker.

Kara Walker’s recent suite of six etchings, An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters (2010) can also be read as a meditation on the horrors and aftermath of the Middle Passage. The first and signature image, no world (which was also published as a single sheet, illustrated) dramatizes the initial trade and ocean voyage that would have initiated an African woman’s life as a slave. The following five works suggest the panoply of sorrows that have followed. As described by Hilton Als in his October 8, 2007 profile of Walker in the New Yorker, “In Walker’s work, slavery is a nightmare from which no American has yet awakened: bondage, ownership, the selling of bodies for power and cash have made twisted figures of blacks and whites alike, leaving us all scarred, hateful, hated, and diminished.”

Kara Walker. “The Means to an End—A Shadow Drama in Five Acts,” 1995. Aquatint and etching on five sheets of light cream Somerset Satin wove paper, each approx. 34 7/8 x 23 3/8 inches. Edition of 20. Printed and published by Landfall Press, Chicago. Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. © Kara Walker.

Printmaking has been a significant component of Walker’s art from the beginning and her first major print, The Means to An End…A Shadow Drama in Five Acts (1995) – a monumental etching comprised of five sheets – was one of the most important editions of the 1990s. When it was issued, there was heated debate surrounding Walker’s imagery, in which she borrowed the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century vernacular paper cut-out silhouette medium (popular in the South) to create elaborate narratives that metaphorically explored the painful reality of slave life. Many found her representation of African Americans to be demeaning and the events she depicted to be inappropriately explicit. Over time, it became clear that Walker’s intense imagery was intended to provoke, a kind of “antidote to politeness” (Als, 72) that would shock the public into addressing the latent and ongoing problem of racism in this country.

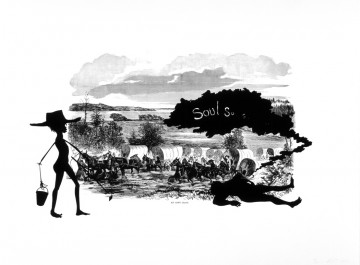

Kara Walker, "An Army Train," from “Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated),” 2005. Offset lithograph and screenprint. Image: 24 x 35 in.; sheet: 39 x 53 in. Edition of 35, printed by The LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies, Columbia University. Published by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Courtesy the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. © Kara Walker.

Over time, Walker has placed her silhouette/shadow figures in increasingly elaborate settings, occasionally appropriating and re-contextualizing historical images. In Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) (2005), Walker borrowed images from the famed suite of prints – which was widely disseminated – that is traditionally celebrated for bringing “realistic” images of war to the public at large for the first time. Shocking in their day, they now seem quaint and tame, promoting a limited perspective. Here, Walker’s shadow figures jolt us into the African-American experience not depicted. This work was included in Walker’s 2006 exhibition, Kara Walker at the Met: After the Deluge, in which she similarly borrowed historical images (from the Met’s collection) and juxtaposed them with her own, generating a moving and haunting meditation on the devastation brought to the African-American community in New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina.

The legacy of slavery and the Civil War has also been a source of deep exploration for Fred Wilson, who first garnered national attention with his 1992 exhibition, Mining the Museum at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, in which he re-contextualized the collections to reveal implicit subtexts of racism. Wilson’s work is conceptual – he does not create art objects using traditional materials, but rather alters or brings pre-existing objects together to provoke dialogue and thought. The questions Wilson raises in his work center around racism and historical representations of African-Americans, particularly in the context of “high culture” and museum display. Because he primarily works with objects from museum collections, printmaking was not a major source of expression for him in the past, but he has created a handful of editions in recent years that add a new dimension to his installation-based work.

Fred Wilson, "ARISE!," 2004. Spit bite aquatint with direct gravure. Image: 20 x 24 in.; sheet: 30 1/2 x 34 in. Edition of 25. Printed and published by Crown Point Press. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

His first set of prints, which were created at Crown Point Press in 2004, explore “the idea of the spot…and images of black that have many meanings” (from a video of the artist speaking about the work on the Crown Point Press website). Because he had abandoned studio practice, Wilson was initially unsure of how he would proceed, but he quickly found an elegant means to express his concept. Using the traditional medium of spit-bite, he dripped acid on the plate and allowed it to etch for varying lengths of time, thus achieving a wide range of black tones. He then animated the spots with “black voices by white writers…Taken out of the context of their original books, they are able to have a conversation with each other about a subject that I, as an African American, want them to talk about” (Crown Point Press video – images and texts are available on their website).

Fred Wilson, "1863," 2006. Archival inkjet with glassine overlay. Image and sheet: 19 ¼ x 27 1/8 in. Printed by Pamplemousse Press, published by Pace Editions, New York. Courtesy Pace Editions, New York.

In 2006, Wilson created a print titled 1863 in response to his exhibition, So Much Trouble in the World – Believe it or Not! at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College (October 5 – December 11, 2005). In direct keeping with his practice of subverting pre-existing images and objects, Wilson altered a hand-colored lithograph depicting a Civil War camp from the museum’s collection titled Camp Massachusetts Sixth Regiment Volunteers, Suffolk, Virginia, dated 1863. When he first viewed the piece, Wilson noticed a minute image of a slave woman hanging laundry in the middle left distance. He then called attention to the figure by overlaying the print with glassine, a semi-transparent paper that is often used to protect prints in storage, and cutting out a small oval that reveals the laboring woman. The “altered” print was displayed in his installation at the Hood and later created as an edition by scanning the original hand-colored lithograph, printing it with archival inks, and overlaying it with a cut piece of glassine. Appropriately, Wilson signed and numbered the glassine, rather than the reproduced military image.

Wilson’s recent photogravures produced at the Brodsky Center for Innovative Editions are a wry take on the museum context itself. Titled The Master Plan (Or: In Between the Big Bang and Modern Art is the Restroom), Wilson altered the floor plan of 22 unnamed museums, blocking out various areas in black. The viewer is left to guess what this signifies. As many floor plans have no black areas at all, one is entirely black, and the overall presence of black is quite limited, it is fair to guess that these areas point out galleries that display work by African-American artists.

Kerry James Marshall, "Vignette (Wishing Well)," 2010, color aquatint etching on Somerset white paper. Plate: 44 ½ x 34 in.; sheet: 53 x 41 in. Edition of 50. Printed and published by Paulson Bott Press, Berkeley. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

In his Vignettes series, Kerry James Marshall takes a more direct approach to correcting the paucity of images of black people in art history (see Marshall’s discussion here) by creating his own paintings of African Americans based on the Rococo style. This period attracted him because the subject matter is generally lighthearted, represents a guilty pleasure for many art viewers, and “you almost never see a black person in them” (interview with Pam Paulson of Paulson Bott Press). The Rococo period is generally agreed to be epitomized by Fragonard’s famous 1767 painting The Swing, which also served as a source of inspiration for Marshall’s recent print Vignette (Wishing Well). In Fragonard’s painting, a pretty young woman, surrounded by lush foliage, is pushed on a swing by a priest while her lover surreptitiously peeks up her dress. In Marshall’s print, a young black woman in a landscape, surrounded by an effusion of flowers, stands with her back to a wishing well, throwing coins over her shoulder, while a hidden figure watches in the shadows. In the same vein, two additional new prints, Untitled (Woman) and Untitled (Handsome Young Man), depict contemporary African Americans in the style of historical formal portraiture. These new prints and others will be on view at Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, February 24 – April 2, 2011.

Kerry James Marshall, "Untitled (Handsome Young Man)," 2010. Hardground etching on Somerset white paper. Plate: 16 x 12 in.; sheet: 22 ½ x 19 in. Edition of 50. Printed and published by Paulson Bott Press, Berkeley. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

A 1996 print by Marshall, titled Mementos (illustrated top) is the most straightforward among the prints discussed in its homage to Black history and is perhaps therefore an apt one on which to conclude this selected exploration. The print is closely related to the Souvenir paintings that were shown in Marshall’s multi-media installation of the same title at The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago in 1998. The images acknowledge the loss of Civil Rights and Black Power Movement figures, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, the four girls that were killed in the Birmingham church bombing, slain Freedom Riders, Black Panther leaders, and others. In the center is an example of “We Mourn Our Loss” banners that were collected at the time. The large female figure holding the vase of flowers is, in Marshall’s words “an angel of annunciation, who looks out at us, acknowledging our arrival and inviting us to come in and remember all the people who are represented there.” Marshall’s intent for the Mementos exhibition and the Souvenir paintings was to pay homage to – and keep in the public eye – the struggle for Black equality in the 1960s. As stated by curator Hamza Walker in his essay for the exhibition catalogue, “Mementos is about remembering so as not to forget the past is still not over,” a sentiment that is echoed in the work of all four artists discussed here and one we are wise to consider as we honor African American History over the coming month.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Ink | “Remembering so as not to forget the past is still not over”: Selected Meditations on Black History | Art21 Blog -- Topsy.com