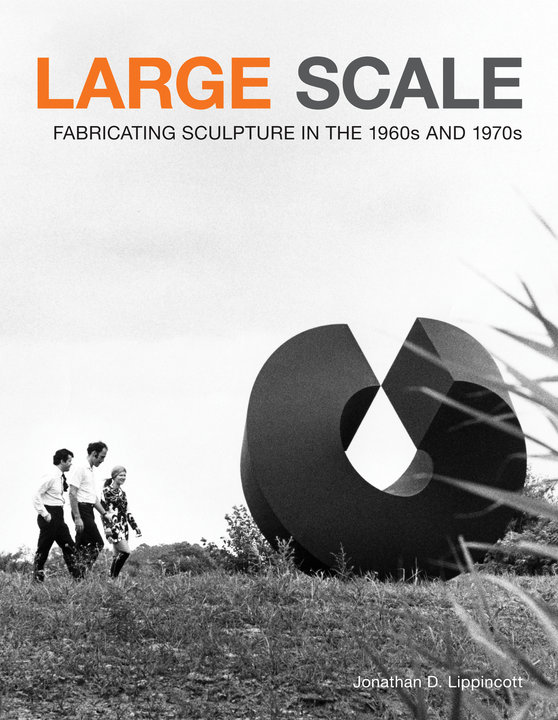

Clement Meadmore’s "Split Ring," 1969, with William Leonard, then director of the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati, Don Lippincott, and Roxanne Everett, in the field at Lippincott, Inc. (One of an edition of two. Cor-Ten steel. 11'6" x 11'6" x 11'. Portland Art Museum, OR. Art © Meadmore Sculptures, LLC / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph by George Tassian, from the catalog Monumental Art, courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH.)

It’s not often that so many of my interests come together in a single book, but the arrival of LARGE SCALE: Fabricating Sculpture in the 1960s and 1970s, which was published last fall by Princeton Architectural Press, marks such an occasion. As an art conservator, I’m very interested in from what and how contemporary art is made because it informs us on how to properly care for it. I also have a ongoing interest in documenting the creation and display of public artworks. As a definitive resource, LARGE SCALE brings all of this together. To find out more about the context of this book, I spoke with its author, Jonathan D. Lippincott.

Jonathan was born the year after the first sculptures were made at Lippincott, and grew up watching the work taking place there. Since 1994, he has worked at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, where he is the design manager. He has also worked independently as art director and designer for a range of illustrated books about architecture, landscape, and fine art.

Jonathan Lippincott, age six, speaking with Claes Oldenburg at Lippincott, Inc. in September, 1973. His parents, Jonny and Don Lippincott, look on. Photograph copyright Roxanne Everett/Lippincott’s LLC; used with permission.

Richard McCoy: In the Preface, you position LARGE SCALE as an historical document about the fabrication of some of the most important sculptures of the era, and make the point that the process of fabrication is often overlooked in art monographs. Will you talk about how you put this book together from Lippincott, Inc’s archive?

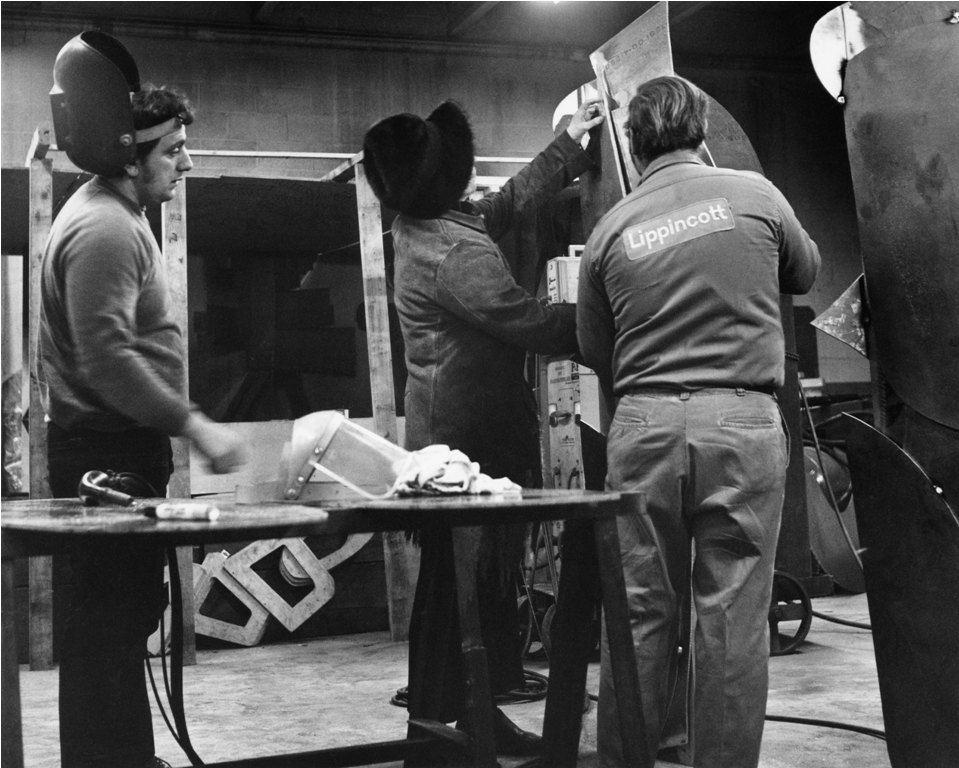

Jonathan Lippincott: In putting together this book, I was working primarily from the photographs taken by Roxanne Everett, who was my father, Don Lippincott’s, first business partner. She and my father dreamed up Lippincott, Inc. together in the mid-1960s.

Right from the beginning, she felt it was important to document the art as it was being made and the collaborative aspects of the fabrication process, in part so they could show other people what they were doing, but also because this was a new idea–to have an industrial fabrication shop dedicated exclusively to working with artists to create sculpture.

They showed these photos to other artists and used them in publications. But really, what interested her the most was the idea of documenting the step-by-step process of how these large scale sculptures came into being.

RM: How big is the archive of photos and documents that Roxanne and your father created?

JL: I’ve measured it to be about 18 linear feet of material. For the book, I went through the entire collection of photographs, which totals more than 10,000. I also went through all of the documents. I did this to see what was there and to organize the material in a way that would be useful for making the book. I identified the photographs in terms of the artist, sculpture, and year. After that, I made an initial edit of about 1200 images, which I then scanned.

With these images, I began to lay out the book, ending up with about 350 photographs. I tried to get a good cross section of the artists who worked with Lippincott, and a range of photos of fabrication and installation of the sculptures.

Louise Nevelson at work in the shop on her sculptures in the series "Seventh Decade Garden," 1971, with Bobby Giza and Bob Sanford. (© 2010 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists' Rights Society (ARS, New York, NY)

RM: I’ve had the book down in my lab for the past month and I’ve realized that it’s one thing to understand it as a form of documentation but on another level, with all of the photographs, it’s really just a pleasure to look at.

JL: Oh, good! Honestly, that’s one of the things I was really trying to capture. As I child going to the shop I can remember knowing how much everyone enjoyed working there. Roxanne’s creation of the archive was very much in this spirit of wanting people to know, enjoy, and get excited about sculpture.

Often times, historians try to represent an artistic era with the work of just a few artists. But over the years, almost 100 artists made work at Lippincott, Inc., and I felt that one of the aspects of Lippincott that was really interesting was the variety of work that was made there. The book focuses on the core group of artists that had a lot of work fabricated there in the 1960s and 1970s.

While a sculpture was being fabricated, the artist would be at the shop often to watch and guide the process. The proximity to New York City allowed artists to come up for the day as often as they liked, and some would come for several days while their work was underway. For example, Claus Oldenburg and Robert Murray would often come up for a week at a time and stay with my family or at a hotel, and they would be at the shop every day talking to and working with the welders and talking to my dad; they were participating in the fabrication process. This was very much a kind of group studio situation were many people were directly involved.

The shop was also open to a lot of visitors. Art dealers, people from museums, and some of the bigger collectors would come up and visit. There were also a lot of school field trips over the years.

There was a big field in front of the shop where the sculptures were on view so people could come see them and develop an understanding of this kind of work. It’s so hard to visualize what a large-scale work will look like if you only see a model or drawings, so having these finished works on display was very important.

Especially early on, this was a new idea and a new approach to the creation of art. People might have known about David Smith or Alexander Calder, but there was little modern sculpture on display in cities or museums when this started.

Two of the three exemplars of Barnett Newman’s "Broken Obelisk," 1963–67, on display in the field at Lippincott. Cor-Ten steel. 26’ x 10’6” x 10’6”. Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Rothko Chapel, Houston, TX; University of Washington, Seattle, WA. © 2010 The Barnett Newman Foundation, New York, NY / Artists Rights Society (ARS, New York, NY). Photograph by Donald Lippincott.

RM: Personally, I find the fabrication of sculpture as interesting (and some times more so) than the finished product.

JL: Absolutely. It was always so strange to me when I would read certain art books about artists who had worked with my father, and the fabrication process was barely mentioned. They would talk about how an artist came up with an idea for a work and then say quite simply, “and then it was sent to a fabricator.” But we know that there was a lot that happened after the artist came up with the idea, and that the artist was involved in that fabrication process as well.

At Lippincott, Inc., there isn’t an example of an artist just dropping off a set of plans and then saying, “call me when you’re done.” All of the artists were engaged, and I think all of them had a great time working at the shop. They were excited to see their work being realized; it was an integral part of their artistic process. Even for the artists who knew how to weld or made things on their own, the scale of the shop allowed for a body of work to be realized that nobody could do by themselves, in their own studios.

George Sugarman, watching the fabrication of his "Baltimore Federal," 1977–78. Sugarman’s model is on the table behind him, at the lower left of the photograph. Painted aluminum. Edward A. Garmatz Federal Building and United States Courthouse, Baltimore, MD. Art © Estate of George Sugarman / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

RM: The book illustrates this with a number of photos of artists comparing their maquettes to an in-process version of a sculpture.

JL: The artists would bring models or drawings to the shop as a basis for their larger-scale works. But it wasn’t like simply hitting “enlarge” on the Xerox machine.

There were always adjustments to size or specific angles, and to the overall feel of the sculpture, because the experience of a small object on a desk that your looking down on is much different than the experience of looking up at one in a field. The object becomes changed and there are adjustments that must be made along the way for it to work.

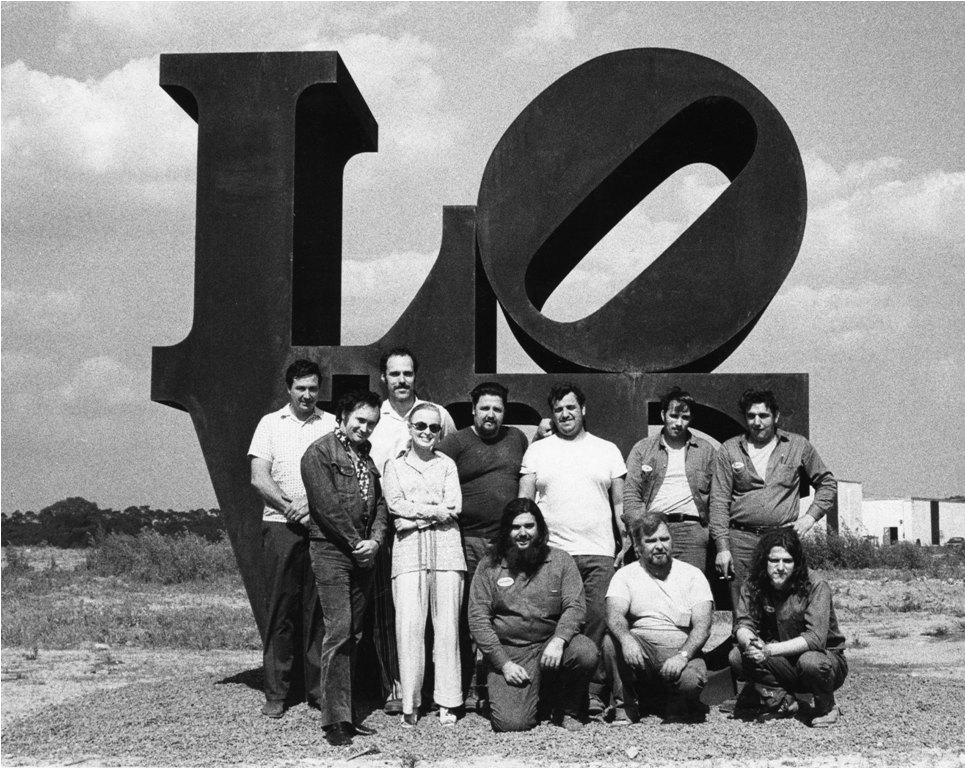

RM: In the IMA’s collection there are two sculptures that were fabricated at Lippincott, Inc. Both are by Robert Indiana: LOVE (1970), and Numbers 0-9, The Ten Stages of Man (1980-83). From the documents in our files here, it’s pretty clear that Indiana was interested in documenting the fabrication process.

JL: Indiana was always very good about documenting; he pretty much always had a photographer with him, and he was a very good record keeper of that kind of thing. I think that the photograph of him in front of the first LOVE that’s at the IMA hung in the office the whole time that the shop was open.

Robert Indiana and the Lippincott crew stand in front of "LOVE," 1970. Front row, left to right: Indiana, Roxanne Everett, Toad, Bob Sanford, Peter Versteeg. Back row, left to right: Bill Rosco, Don Lippincott, Frank Viglione, Eddie Giza, Joe Lesco, Bobby Giza. This piece was shown for the first time at the Indianapolis Museum of Art as a part of "Seven Outside" in 1970, when it became part of the permanent collection. Cor-Ten steel. 12' x 12' x 6'. Indianapolis Museum of Art, IN. © 2010 Morgan Art Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS , New York, NY. Photograph by Tom Rummler.

RM: There’s a good 1975 interview with your father at the end of the book in which he talks about the difficulties of the material from which LOVE was made, Cor-Ten steel, which of course many artists were using at this time–from Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk to Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc. In 2005, our LOVE underwent a fairly interventive conservation treatment. Sections of the metal that had become structurally unstable were replaced and to get the patina even, we stripped the sculpture down to bare metal to allow the patina to re-develop.

JL: That’s really the only way to do it – for the surface to look even, it has to all age together. I don’t think anybody has ever figured out a way to do anything else. I know that’s what my father always recommended, and other places that have sculptures in Cor-Ten that have done the same thing.

I think Cor-Ten is a gorgeous material and I’m glad people have continued to use it and care for it. But it does present its challenges.

RM: We’re not alone at the IMA with our issues with Cor-Ten steel. Having visited Richard Serra’s work at the Guggenheim Bilbao, I know that they have to deal with people touching and putting graffiti on the Cor-Ten arcs there. But in the end, there’s not much that can be done.

JL: It’s incredibly rare that anyone goes into a museum and runs their hands over the paintings, but for some reason people feel compelled to do it to sculpture. Unfortunately, this is one of the challenges with showing sculpture.

RM: Your father now takes an active role in the preservation and restoration of sculptures. This seems like a natural role for him to assume. Will you talk about Lippincott’s role in preserving artworks?

JL: In some ways, this role is one that [Lippincott] morphed into easily as time has gone by because a lot of the sculptures he helped fabricate have been on view outdoors for 30 years or more. Even in the early days, they assumed this kind of role. Artworks would come back from an exhibition in which all 500 people had touched the sculpture and damaged the paint, climbed on it, or some like that. So Lippincott was repairing sculptures all along.

As time has gone by, this is something that they’ve increasingly become involved with. They do a lot of consultations with museums and places like Storm King Art Center, as well as for private collectors.

For exactly this reason, right from the beginning they were incredibly meticulously with their records. They knew that 5, 10, or 40 years later someone was going to come to them and ask how a sculpture was originally fabricated. There was always a consideration about how these things were going to be cared for over time.

RM: What are the plans for the long-term care of the Lippincott archive?

JL: This is something my father and I have talked about a lot. There are two elements to the archive, the photos and the documents. Now that the book is completed, we don’t need constant access to photos, and I would like them to go to a place where they would be available to students and museums and artists, since it is such an amazing and, I think, unique collection.

The documents are still in use, my father and uncle refer to them often, so that’s something that they would want to keep for now, but ultimately that too would be best in a place where people would have access to it.

Ellsworth Kelly, right, and Don at the shop, looking at Kelly’s "Curve II," 1973. Weathering steel. 117¾" x 123½" x 1” (299.1 x 313.7 x 2.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Gift of Philip Johnson. © Ellsworth Kelly. EK 507. Photograph courtesy of Ellsworth Kelly.

Pingback: The Life and Ages of Robert Indiana’s “Numbers” from Cradle to Repaint | Indianapolis Museum of Art Blog

Pingback: Visual Arts Briefs » Blog Archive » Public Art, Modern Icons

Pingback: Roland, Bold and Beautiful | Mark Masuoka's Blog

Pingback: Roland, Bold and Beautiful