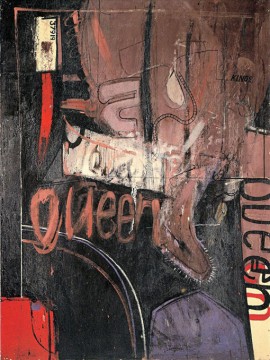

I recently visited the Tate Britain with a friend who studies history but doesn’t care much for modern or contemporary art. Standing in front of David Hockney’s Great Pyramid at Giza with Broken Head from Thebes (1963), she asked me to give my “art historical” opinion on the painting, presumably as explanation for the painting’s more abstract elements. I commented on the exposed canvas representing sand and the sketchy, half-visible figures, suggesting that the work could represent a memory of a person, or maybe a mirage. I also pointed out what appear to be butt-cheeks floating amorphously near the solid broken head. My “explanation” ended there, and I felt embarrassed about how little it must have helped her. (If only it had been one of Hockney’s pool paintings, I might have had more to say!)

The incident brought to mind others where my non-arty friends had asked for or mentioned my “expert opinion” on some artwork or another. Perhaps these are just my own insecurities showing, but I tend to push away the idea that my studies toward a Master’s degree in art history mean that my opinion or feelings about an artwork should be deferred to in favor of someone else’s, at least within a casual context. An image or artistic experience can evoke an infinite amount of responses, and I dislike the idea of granting hierarchy to opinions. On the other hand, if all analyses of art are made equal, then what value do we give to the advanced study of art history?

I’ve heralded my belief that art, in all the diversity of its forms and content, should belong to everyone, that every and any person should feel that art belongs to them in some way. That sense of belonging is directly related to a person’s or group’s membership to the cultures in which they live, and are critical to understandings of identity and agency. As such, universal accessibility, both physically and intellectually, to art is key. However, the question of what intellectual accessibility entails remains ambiguous to me. Does access = “getting it?”

Caroline Lagnado’s “Dumbing Down the Art Museum” post and the comments-conversation the post inspired hit at the heart of this issue for me. I do agree that much, if not most, artworks rely on an understanding of the historical and social context for a deeper understanding of their meanings (this is likely what my friend was really asking for at the Tate). I also agree that art institutions should aspire towards complexity and challenging their audiences. The challenge in challenging people, though, is that the playing fields are uneven: cultural access and consumption vary greatly across class, ethnicity, and racial lines. The different cultural rates of consumption of art are further hindered by historical marginalization of representation (both in content and by artists) from various economic and ethnic backgrounds within the most visible and well-funded institutions. It is hard for me to argue for the elitism of the art world, the same that our careers as art historians, educators, and critics depend on, to continue in light of these inequities.

The question, “Should art be easy?” is a loaded one. What kind of art? Easy for whom, and towards what purpose? I don’t know if the elitism of the art world can be taken for granted without regarding the roles art plays in society. I’m interested in an arts professional career as facilitator, more of a gate-opener than gatekeeper of the world(s) of art. Sometimes it occurs to me that my job as a student of art history is to do the hard thinking and questioning about art that other people might not put in (or realize they can put in) an effort to do. Everyone is equipped to having a thoughtful response about an artwork, but not everyone actually tries to recognize what those thoughts might be.

Furthermore, an art historian or art critic does not give voice to opinions on any and every artwork they encounter. The numerous methodologies and perspectives within art history fracture the idea of a universal “accessibility” or understanding. The diversity of art history gives light to the diversity of art reception in general, although the elitist, intellectually rarefied nature of the academy narrows the expression of that diversity. Is it academic art history’s responsibility to reflect the broad diversity in the name of inclusion? I believe that poststructuralist and postmodernist theory, especially as they inform Marxist and feminist analyses and theory, can be wielded as tools in that struggle, particularly in analyzing the cultural existence of art, but broadened access remains elusive given the intellectually challenging nature of much art theory, not to mention the cultural boundaries that limit who takes on those challenges.

Arts education courses often address issues of multiculturalism, access, and the purposes of arts education, but there seem to be very limited connections between art theory and pedagogical theory. The increased professionalization of the art world, exemplified by the growing numbers of MA programs and graduates in arts administration and arts education, seems yet to fully reconcile the issues of intellectual and cultural accessibility with that of actual art theory. In deciding where to study for my Master’s, I felt torn between studying the more practical side – the methods and realities of educational outreach – and the more theoretical side of art history. I suppose I’m looking for art history to take up arts education’s mantel of further accommodating for difference.

The difficulty of universal intellectual access is informed by the diversity of possible perspectives. Art itself is a very broad abstract for cultural expression and representation, presented in a diverse number of formats, institutions, and contexts, and I value the development of any and all perspectives and responses to art. Ideally the presentation of art will accommodate the diversity of art reception, although not all presentations and contexts can and will function in the same way or for the same audiences. I believe it is art’s social responsibility to reflect and respond to the diversity of these perspectives, but I can’t expect each perspective to understand art to the same depth. Perhaps a more perfect art history recognizes and values the grand diversity of perspectives, and grants access to the pursuit of deeper understand and knowledge of each.

In the end, I think my utopian ideal of a universally accessible art world is not one where everyone understands and agrees on a universal meaning to any given artwork, either by virtue of the “ease” of the work or equally knowledgeable scholarly individuals, but, rather, one where any person recognizes and values his or her own facilities towards deeper understanding of an artwork, however varied those understandings may be. Currently, I’ve found people often approach art as either an all-or-nothing game, either they “get it” or they don’t. My ideal is a society where that binary and its inherent elitism is eliminated, a society where people don’t feel like a lack of historical or theoretical knowledge is boundary against appreciating their own perspective, but an opportunity for developing it further. Art may not be easy, but the sense that a person can get an artwork on their own terms is easier to attain than is often currently believed.