Teresa Margolles, Untitled (2010), October 28, 2010 - August 2011, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Late last night, a friend and I decided to find a restaurant we’d seen once, over a year ago, when walking through Virgil Village to Silver Lake. We remembered the place as being hedged in, strangely, even comically, hidden from the freeway above and from the main road in front of it. When we found it—El Caserio, a “place where you can relax to the explosive tastes of South American and Italian Cuisine”—, we couldn’t figure how to get in. All the entrances were dark, except the door in the back, off a cul-de-sac, that looked as heavy as a drawbridge. It had to be pulled open, frame and all, by a white and black rope, but it took us a good three minutes to figure this out (and then it wasn’t our effort but the help of a man and woman who came after that got us through). Inside, El Caserio has loud music, tall walls, vines, all meant to circle you in and close out any sign (or sound) of cars passing.

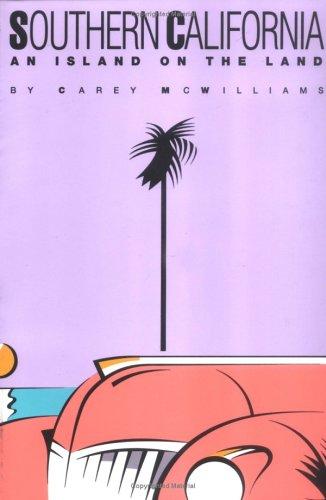

I imagine that Carey McWilliams, that cultural historian whose muscular criticisms were smoothed over by his tender affection for SoCal, would see El Caserio as a holdover of what he called L.A.’s archipelago quality. No cultural or economic lines bisect L.A. he wrote in his book Southern California: An Island on the Land, published over sixty years ago now. Rather, self-reliant, island-like circles enclose communities to the exclusion of others. I still feel that here—circled in when I’m in neighborhoods close to home, or like I’m circle-surfing when I go from East L.A. to West.

There’s a circle on the grounds of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art right now, subtle enough to accidentally overlook but brutal in its own way. It wants to be closed-in and opened-up at the same time, and it’s made up of six low-to-the-ground benches that look to me like Aztecan stairs re-imagined in the International Style—which means they’re earthy, regal, and have a faux, modernistic modesty. But they also have a real modesty that mainly comes from their unaffected smallness in comparison to the big museum behind them.

Teresa Margolles made these benches, which have no title, out of concrete, just as she made six benches for Jardin Botánico Culiacán, a Botanical Garden in Culiacán, Mexico, in 2006. The benches for LACMA—commissioned as part of the young non-profit Los Angeles Nomadic Division’s VIA project, which has installed site-specific works by Mexican artists throughout L.A.—resemble the benches from Culiacán in size and shape, but they have one distinct difference. The concrete for the L.A. formss has been mixed with fluids used to clean four corpses, victims of drug- and gang-related violence, according the press release, at an autopsy room in Mexico. So there are bodies implicit in the concrete, which means if you decide to sit, you’re engaging with violence you likely have no first-hand knowledge of, whether you know it or not.

It’s that last part, knowing it or not, the irks me a bit. How many of the people who walk by the benches on LACMA’s ground will have read the press release? How many who choose to sit will know they’re on objects infused with liquid evidence of human cruelty? Few, I suspect. I certainly hadn’t done my homework when I first felt charmed by the benches’ low-to-the-ground, zig-zagging and quiet arrangement. Sitting on them felt like entering a specifically intelligent, contemplatively circular space, entering a circle inside the larger circle of LACMA (the museum’s recent exhibition of Mexican-American art was called Phantom Sightings and it aimed to highlight the “stealthy” public interventions of the Chicano movement; Margolles, though not Chicana, has stealth too, placing one small community of concrete bodies on the grounds of another). The extent to which I was interacting with a history of violence was lost on me. Knowing now makes me feel like I’ve been had.

It might be symbolic—after all, each community has its own lurking layers of hidden history that many engage unaware—but I don’t want my public art to leave the blinders over my eyes. Even if it’s covert or mysterious, I want to be invited to peek at what’s behind the mystery before I decide to engage.

I guess that’s why I liked El Caserio. After walking around three times, we knew all we could about its context, no press release needed. Then, inside, its attempts to sever itself from the fastness and noisiness of the city it lives in were so explicit (“the ambience is just right,” says the website) that we were at least, during the course of our meal, knowing inhabitants of the inside circle. I don’t mean to undercut the serious, stunning qualities of Margolles’ installation by comparing it with a funny fusion restaurant under the freeway. But El Caserio does get some things right.