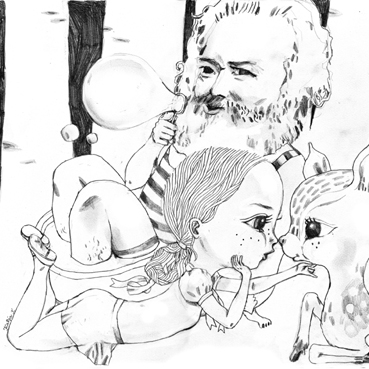

Katja Tukiainen, "Hi, my name is Peter. Do you want to find out why?," 70 x 70 cm, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

In the Deer Forest

“Hi, my name is Peter. Do you want to find out why?” With these words, I became acquainted with Katja Tukiainen. In the back room at a friend’s holiday party last December, I was shown a square bubble gum pink painting above the bed depicting two school girls in identical uniforms: one was pinning the other down, merrily holding a candy cane. Along the bottom edge of the canvas, the caption was painted in cursive handwriting, curving up the right corner of the painting.

Later I met the artist at her opening, Deer Forest, at Hasan & Partners in February. Under a glow from the soft pink lights in the installation, I was introduced to Katja Tukiainen as the girl who loves unicorns. This fact was relevant in Katja’s installation, densely populated with deer, fairies, and an army of adolescent girls. Katja herself appeared to have stepped out of one of her own paintings: she was wearing a vintage bisque-colored dress on which she had inked her dainty deer and fanciful female characters. Encircling Katja was an impenetrably rosy air.

Katja Tukiainen, "Paradis e (Extension of my personality)," from the series of painting installations "Katja Tukiainen: Paradis a-z," Finnish Institute in Estonia, Tallinn, Estonia, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

Nordic Shangri-La

Much like Katja’s installation, I have been living in a dream world in Helsinki, my Nordic Shangri-La. The stipend from my grant releases me from the burdens that my colleagues, recent graduates from Cranbrook Academy of Art, have been facing: finding jobs, apartments, support, etc. From afar, I have been observing their struggles as they embark on the epic quest to find the magic elixir of living and creating as a professional artist. My Fulbright grant to Finland is a year-long placebo, a temporary lapse before this inevitable hardship. Now, as my stay abroad nears its end, the vastness of my future, no longer neatly spliced into more manageable chunks of time, is starting to weigh on me.

Thinking about the future is overwhelming, so I’ve been thinking more about the present, specifically my time here in Helsinki. Because the structure of the Fulbright can be quite loose, designed flexibly to accommodate specific projects, my experiences with the educational system in Finland are hardly the norm. Being a non-matriculating student at Aalto University offered me a glimpse of something wonderful—albeit from the outside—like peering through the window of a fabulously furnished apartment as you shuffle home to your sparse room in student housing.

Finland has been endlessly touted in the media lately—from the Newsweek article last August crowning Finland with the title of “Best Country” to the endless reports about its winningest PISA score. (PISA, which stands for the Program for International Student Assessment, is the international scoring system that rates the literacy of a nation’s 15 year-old pupils in mathematics, science and reading.)

I asked Katja Tukiainen to meet with me because she is well-versed in the Finnish educational system. She holds two Master’s Degrees and she is currently working on her DFA (Doctor of Fine Arts) at the Finnish Fine Arts Academy. In addition to a shared love of unicorns and kitsch, we both have studied in Venice, Italy, and at Aalto University. Over a pot of green tea on a cloudy afternoon, Katja generously relayed her educational experiences to me.

Though she was always supported by her family as she pursued a profession in the arts, Katja desired a stable career. The ability to support herself factored into her decision to seek her first Master’s in Art Education at TAIK (now part of Aalto University). While working on this first degree, Katja studied abroad for one year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice. Katja began to pay more attention to the treatment of women in Italian culture as a student in Venice. She explained that while she had never experienced any form of sexism in Finland, equality among the sexes was not as assured elsewhere. Later, when she lived in India, the disparity between the sexes in this society definitively sealed an interest in gender equality in her work as an artist. Her roots in punk rock as a teenager informed her rebellious and independent nature; however, Katja was hesitant to call herself a feminist until much later in her career. (Feminism is, after all, still kind of a dirty word.)

After she completed her first Master’s Degree in 1996, Katja worked. She had a job and she made art; she was successful at both. Still, something was missing. So, Katja decided to return to school at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts. She wanted to be a part of a dialogue—about her work and about the work of others. A sad aside about the educational systems both in Finland and the United States is that academia frequently appears to be the most conducive setting for meaningful discourse about art. At least, this is my fear—and I am not alone; this question has also been addressed recently by the BHQF in the United States, among others.

Beyond the fact that artists fret over the quality of art talk post-graduation, I am all too aware of an additional worry. I have had in-depth conversations with three Finnish artists, all of whom mentioned (in one way or another) that there simply isn’t enough conversation and training for the world beyond school. This same deficit applies to my life after graduate education in the States. There simply isn’t enough time in a two-year program to work and address more pragmatic issues like what actually happens after school. Moreover, it is often taboo in this environment to get into the nitty-gritty about the mechanics of how artists actually interface or evade the arbitrariness of the art market. For Katja and her peers in the post-doctoral studies department at Kuvataideakatemia, the DFA program is no reprieve or temporary deferment of the bane and boon of a career in the arts. No funding is provided for doctoral studies; hence most students work and study simultaneously.

So, how does the Finnish DFA program work?

It takes a minimum of three years to complete the mandatory coursework. During this time, Katja has been participating in monthly seminars, critiques, and discussions with other students. Together, Katja and her peers read each others’ writings and they talk about each others’ work. The program is relatively new and as such, it is indeterminate. Less than a dozen artists have graduated with a DFA from the Finnish Fine Arts Academy since the program was established in 1997. At the end of the degree, the DFA candidates must defend both the written component as well as the material from the artist’s production.

Upon completion in the coming years, Katja will defend her thesis. Katja’s work will culminate in a book; Paradis will be a collection of twenty-six installations and the accompanying texts, each one named after one letter in the English alphabet. The tone of the writings varies with the installations and paintings. Sometimes Katja adopts a more scholarly voice, but she always speaks from the perspective of an artist—never with a put-on or over-intellectualized front. She stressed that artists should not try to be philosophers or art critics when they write. There is merit in the point of view of artists that become compromised when artists ineffectively try to wax philosophical. Furthermore, what is most important to Katja is that she enjoys the writing as much as she enjoys the painting. The process and product for both mediums must convey a sense of her pleasure.

And Katja’s work is pleasurable. At first, it is easy to swaddle yourself in the fluff, to willingly, unquestioningly give into the saccharine glut of nubile femme fatales. The feminine jouissance uniformly announces itself in her work. Upon closer inspection, the thread of utopia running through Katja’s work reveals a frank reflection of the unreachable, the unattainable.

The unattainable takes the form of a female avatar. Sometimes there are men in Katja’s paintings, but the protagonists are invariably female and they are almost always very young. There is a reason for this: Katja believes that there is a sense of mysticism in adolescence—a curious and blinding brightness to life’s possibilities in the territory between adult and child. At the precipice of this liminal space, girls and boys part ways. Gender roles enforced by society can be most volatile and most aggressive in adolescence and early adulthood.

This aura of adolescent mysticism mirrors the experiences of the MFA candidate, or any artist in school. We artists tend to fantasize about how we will find acclaim. Against the odds, we will ensnare success, wild Chimera that she is. Outside of school, clouds of torpor rain down, washing away the fables of magical thinking. Like boys and girls, dilettantes and professionals are crudely separated from the fold of recent MFA graduates. Maybe there could and should be more of a nod to the practical in the education of artists, but not at the expense of the—dare I admit it—irrational belief that the arts can and do change the world.

We can’t all be escape artists, but Katja is. As such, however her work is not soft on content or politics. Her paintings, comics, and installations invite the viewer into another world—a better one, a pink one. Leaving that world behind begs questions about what the real world actually looks like. Soon I will find out for myself. I will leave Finland with the image of pink clouds emblazoned in my mind, with Katja’s words: “feet on the ground, head in the clouds” in my thoughts.