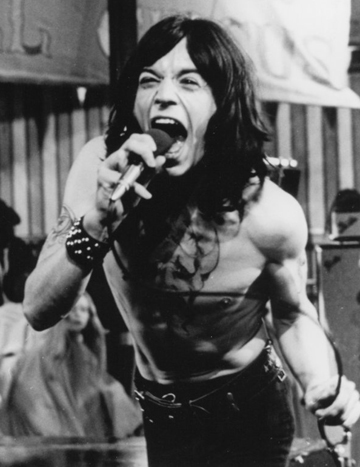

Mick Jagger, 1968. Photo from "The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus" © 1996.

In an interview for Rolling Stone, Mick Jagger described the 1969 hit “Gimme Shelter” as a song about apocalypse, about the end of the world. He channeled the rage of an era, popularizing dissent in the face of the devastating visibility of war: “Oh, a storm is threat’ning my very life today; if I don’t get some shelter, oh yeah, I’m gonna fade away.”

In 2011, performance emerges out of the “storm” — that cultural flux set in motion by the turmoil of social order over the past ten years. As markets collapse, we are beginning to question the values and beliefs that have contributed to current states of personal and political devastation. Performance has the potential to transform the wreckage into something worth seeing, discussing, and arguing about.

With an amorphous history as a fine art threading back through visual art, theater, dance, video, and photography, performance is usually the medium artists use to rebel against definition or to critique the constraints of other art forms, politics, and socio-economic issues within both the art world and the real world.

Art21’s newest column, Gimme Shelter will feature essays, interviews, “studio” visits, documentation, creative responses, evaluations, and propositions of performance. Posts will shift between current work and historical reference points, as new connections and developments converge. What is at work in the translation of experience is an engagement of faculties beyond the normative gaze. At the core of this column is the unique voice that comes from the subjective experience of the live event. The only way to go forward, right now, is to step up with your whole body and literally, move there.

Marina Abramovic "covering" Valie Export's "Action Pants: Genital Panic" in "Seven Easy Pieces." Documentation by Babette Mangolte.

In 2005, Marina Abramovic performed the game-changing Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim, where she adapted seminal performances by Joseph Beuys, Valie Export, Bruce Nauman, Gina Pane, and even her own work. A circular platform on the first floor acted as a type of proscenium where she re-enacted works for hours and hours and hours. It was pre-MoMA. It was the verge of performance fever. Abramovic made visible a canon, so to speak, of Performance Art that had, up to that point, rested in photo archives.

I remember standing for hours on the slanted spirals of the Guggenheim, watching Marina lay on ice and flames, press her body against glass, cut into it, and sit with her crotch exposed. Marina’s body had broken into the museum and created a dérive of its landscape. This action generated much debate about the efficacy of re-enacting ephemeral art and of a perceived cult of personality, as the artist made spectacular works that were made to confront the gaze and permissiveness of the viewer. While convincing arguments can be made about both sides of the experience, the fact remains that performance is invading every corner of the art planet. It was the same year of the inaugural Performa Biennial that, six years later, will now be celebrating its fourth term in Fall 2011.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmozx7m6-IU]

The image on this column’s header is of Everyone, a performance by Miguel Gutierrez and the Powerful People at Abrons Art Center, NY. It happened on stage with the audience seated on stage. Nine dancers and one musician. At one point in the show, the curtains pulled back to reveal the empty seats of the theater. From my vantage point, I could see two dancers standing in the seats, slowly raising a right leg and a left arm to extend toward an arabesque. Eventually, the dancers left the stage and started playing in the seats and aisles. There were moments when a dancer would stop and observe us sitting on stage. The watchers being watched. It was simple; we were both performing.

By the end of the piece, the dancers piled back up on the stage and started making out with one another. This happened for a long time, and I remember they switched at some point. I was a voyeur. I learned as much about the dancers’ tongues as I did about the arms, legs, and heads I been watching for the past forty-five minutes. I came to see what I thought would be a dance, but was it?

There were dance-like movements, but there was also running, touching, playing, singing, talking, and making out. That was it for me, the time when I realized there was more to watching and to being watched, a more complex relationship to the performers, to the space, to the other audience members, and to my own sense of freedom and agency as an audience member. It’s not that problematizing the performer-audience relationship was new, but that in a socio-political climate of surveillance, restriction, fear, and paranoia, I could be surprised, I could be “included.” There was a legacy here: of Dada, of Brecht, of Fluxus, of the Judson Dance Theater Movement, and even of the wayward Satanic Manson family commune.

Gimme Shelter is a monthly column on performance now. It is a space to talk about the momentum and expansion of this field as it proliferates and unfolds without a singular origin or destination. It is an orphan of the arts, but it doesn’t need to belong. In warehouses, black boxes, museums, abandoned factories, churches, basements, galleries, rivers, court rooms, empty swimming pools, bedrooms, studios, clubs, opera houses, rooftops, wherever it is in the moment is where it belongs. While this might be a survival mechanism of the form, in these economic times, its utility is making an impact.

Marissa Perel is a performance artist, writer, and independent curator. Her performance, video, and text-based work has been shown in New York, Chicago, and Central and Eastern Europe. She writes for her own Body Blog as well as for Time Out, Bad at Sports, and Tarpaulin Sky Literary Journal. Perel received her M.F.A in Performance at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and B.A. at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University.