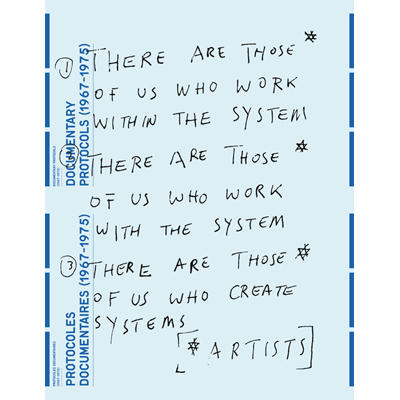

Cover of "Documentary Protocols" (1967-1975). February 2010, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. 416 pp., b.w. illustrations.

In light of the dialogue that Occupy Wall Street has brought to the surface, I decided to interview Erin Sickler, a New York-based curator, about her experience with the Arts & Labor movement.*

Amanda B. Friedman: Can you share a bit about your engagement with the current Arts & Labor movement spurred by and connected to Occupy Wall Street and your involvement in this dialogue prior? And, can you elaborate about your experience and broader notion of working in the arts. Where does your interest in labor and the arts come from?

Erin Sickler: First, I want to say that I only speak for myself as an individual participant in the Arts & Labor group of Occupy Wall Street and in the Occupy movement, and not for Arts & Labor as a whole. The idea of the 99% is not without problems or contradictions, but it does provide a useful umbrella for multiple voices, positions and opinions to emerge within a common purpose. I am just one of those voices.

You could say that an oversimplified trajectory of contemporary art goes something like this: ideas about art realized in the work of artists based in Western Europe in the late 19th to early 20th centuries influenced forms of art coming out of the United States in the mid to late 20th century, which influenced the globalized art world we have today (one that is still heavily weighted towards artists from the US and Europe, but occasionally recognizes artists outside of that). Within this timeline, a certain number of artists are skimmed off the top and canonized by history. What remains is what Gregory Sholette identifies as Dark Matter—all those artists that have been marginalized by this trajectory as well as those who have proposed counter-tactics to call the status quo into question. These artistic hierarchies are not merely aesthetic but aligned with larger economic, political, and historical arcs.

I often take up my position as a curator to try and tease out some of these complicated relationships, albeit in subtle ways, more or less at an affective level versus a didactic one. In part, I think this is because I came to art through the back door. I started making art in college at Oberlin. Coming from a working class background, I had little exposure to contemporary art as a child. Oddly, I think it was a reaction to that rarified academic environment that pushed me towards art making. It wasn’t that I did not enjoy theoretical debates—I actually quite liked them—but I also found them alienating. Within that context, practicing art was a way to stay grounded. Quite simply, it was the only place I could use my hands. Of course, knowing what I know now, it all seems so ridiculous that I thought of art as any less rarified then theory, but I think that by sliding sideways into art, it made me sensitive to what was being elided or overlooked in the dominant discourse, on a variety of aesthetic, affective, and social levels.

There are many reasons that people remain silent about labor conditions in the art world. Talking about auction values or questioning capitalism is fine, but try bringing up the actual working conditions of artists or other laborers within art institutions. In my early twenties, I supported my creative ambitions through all kinds of low-wage service jobs, usually several at a time. Later, I held positions in a variety of art worlds and became a curator because it seemed more stable than being an artist (I was wrong). I have visited hundreds of artists’ studios and heard about their often-precarious economic situations. I have seen art writers, administrators, and other curators struggle to stay afloat on measly salaries with no benefits or health care. I also recognize that many of us who work in the arts chose this fate and that people who don’t have access to these same choices do a bulk of the labor in the art world and the world at large. Someone just gave me Hans Abbing’s book Why Are Artists Poor? (2004) which teases out the inverse relationship between artists’ low incomes and the high symbolic value of art.

Arts & Labor is trying to break the silence around these issues. At least at the outset, people came to Arts + Labor through their involvement with Occupy Wall Street, so in different capacities we are all aligned with the issues and actions of economic oppression. Right now, we are in the embryonic stage, but our group is a fairly broad range of positions within the visual arts field and we are seeking to build broader solidarity with workers in other creative fields as well as other workers.

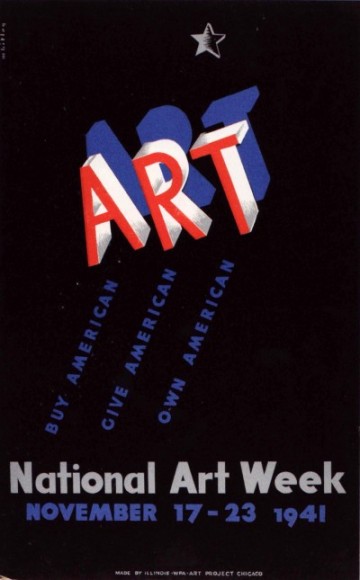

ABF: I really enjoyed Sunday’s Occupy Wall Street Arts & Labor Teach-In with Andrew Hemingway and Gregory Sholette who (as noted on the event invitation) “presented on and lead a discussion on artist-workers under the New Deal, the Federal Art Programs (1933-43), and the Art Workers’ Coalition (1969-1971) and screened L.O.V.E.’s (Lesbians Organized for Video Experience) Purple Dinosaur (1973) which was a short video featuring a big purple paper mache dinosaur that was wheeled into the streets to the American Museum of Natural History (NYC) in a protest demanding that feminists be hired, and that a non-patriarchal view of history be represented by the museum.”

From where you stand, what are the key connections between today’s Arts & Labor, W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy), and other groups advocating for working artists and arts workers and the Art Workers’ Coalition (1969-1971)?

ES: I think that the single most important thing about learning about the Art Workers’ Coalition, as well as the John Reed Clubs, and the Artists Union from the 1930’s, is that it provides a historical precedent for art workers self-organizing. Those histories are not well known. Learning from their successes and failures can help us think through what might be possible now. I believe that W.A.G.E. is a valuable ally for Arts & Labor and some of their members attend meetings. They have been focusing on one very specific goal, which is getting institutions to pay artists fees. The momentum of OWS will probably help them to do that and more. Within Arts & Labor, there is a broad range of initiatives from mapping power in the existing art world to imagining what an alternative art world might be. Some of these interests overlap with W.A.G.E. and it seems like everyone is open to collaborating when possible.

ABF: One of my take-aways from the discussion was how Gregory brought up the model of non-organization that the Art Workers’ Coalition (1969-1971) used in their meetings compared to the general assembly model that Occupy Wall Street and the Arts & Labor groups are putting into action. What are your thoughts on the general assembly model?

ES: The consensus model is not perfect by any means, but if you are trying to foster a movement—meaning you are trying to get enough people together to make some basic commitments about implementing change—you need a structure that has the capacity to take into consideration the ideas, plans, projects, and opinions of a fairly large group of people. The 60’s groups had no model for that, and so they fractured. And, on a more subtle level, they could not support the diversity of opinions necessary to imagine different structures, so their actions were fairly conservative. I am hoping that with this model we can achieve more.

ABF: Where do you see the momentum around Arts & Labor headed? The world of art is entrenched with issues of class, dependence on corporate monies, and the like. Gregory showed that great image of a banking ad with the Guggenheim in the background. Can you share some of what you have been working on in the alternative economy sphere?

ES: This is a really big set of questions that I have been researching for a long time, but in a more concentrated way over the last several years. I have held several workshops on alternative art economies that grew out of events I was hosting called Idea Parties, which were really group brainstorming sessions to encourage creative people to self organize. I had been doing work with alternative spaces like ABC No Rio and looking into forgotten histories such as the artists involved with the 80’s homesteading and squatter movements in the Lower East Side and issues around gentrification. The retail sessions at Mildred’s Lane also contributed to my thinking about mercantile capitalism and other transitional modes of economics, as did the interviews conducted by artist Oliver Ressler on alternative economic systems. Ongoing conversations with friends like Caroline Woolard of Ourgoods and SolidarityNYC, artists Mary Billyou and Huong Ngo, and food researcher Elizabeth Jones of Grow NYC, have provided much fodder for this research.

This past spring, over the course of three workshops, I collaborated with artists to put together a primer of documents and links related to alternative art economies. In the end, this compendium of texts came to 962 pages with links to additional bibliographies and reading lists. I spent the summer pouring over these materials and trying to draw some conclusions, or rather, trying to find some potential openings for envisioning an alternative. Even though I was familiar with most of the material and its historical and theoretical precedents, I had a difficult time digesting it all. I compiled my reflections into an article that will come out in the March issue of the journal Rethinking Marxism, which lays out some potential directions for moving to a healthier art economy. Now with OWS, however, everything feels a little up for grabs, but I am grateful that there are now so many more people interested in this topic.

ABF: Since it is nearing the end of the year, can you list some top exhibitions you have seen in the past season? Do you have any final thoughts you would like to air on the subject of Arts & Labor and Occupy Wall Street?

ES: I really liked both the Brion Gysin and Paul Thek shows that happened last year around this time and the Harun Farocki show at MoMA. Also, Kara Walker and Amy Sillman in Chelsea. I think that shows at Artists Space have been consistently strong and at Third Streaming as well—I loved the Alvin Baltrop show and one of my favorite young New York artists Jayson Keeling has a great show up there now. I also like what the Hunter College folks have going with The Artist’s Institute, although I have not attended as much as I would like. As far as Arts & Labor or Occupy Wall Street, if you are an art worker in New York and these issues speak to you, please come and find us. That’s all I have to say about that.

Paul Thek. "Untitled (Earth Mandala)," 1974. Gouache on eight sheets of newspaper. 22 1/2 x 33 in. (57.2 x 83.8 cm) each.

*[Editor’s Note: To read more from Erin Sickler, see Erin’s blog posts, written during her guest-blogging stint for the Art21 Blog in May and June of 2010].

Pingback: Occupy and the Arts: Curating by Consensus in Lower Manhattan | Createquity.

Pingback: Occupy and the Arts: Curating by Consensus in Lower Manhattan | Songcography.com

Pingback: ++jose emilio rodriguez++blog » Just for you Nimet