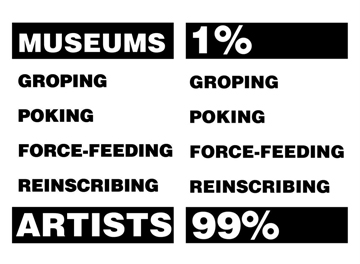

Signs created by LA artists in response to the controversy over the 2011 MOCA Gala, choreographed by Marina Abramović.

Since Occupy came to LA, I have been present for many beautiful, challenging, inspiring, joyful, frustrating, and moving events. I have visited Occupy encampments in both my immediate and professional communities. I have initiated a drive to provide Occupiers with blankets, washed LA City Hall with Mother Art (an action initiated by Tucker Neel), read “A User’s Guide to (Demanding) the Impossible” aloud at an Occupy LACMA action, talked endlessly with friends who participated in the notorious 2011 MOCA Gala, and spent the first hours of my thirtieth birthday watching friends get arrested on Ustream feeds while telling another, on the phone, to get away from the LRAD she described standing next to. The event that I want to discuss most, however, is the creation of a union, or something like it, to address what is obviously a very failed system.

I’m not even sure the problem is systemic, but as Sara Wookey’s letter addressing the equity controversy at the MOCA Gala points out, there is definitely a problem. Since there is plenty of literature on the event and its aftermath, I will not recap it for you, but it was directly after a protest of that Gala that a few LA artists began to organize towards a local art union. (Note that as a group, we are not yet sure of the terminology we want to use in naming ourselves, but for the purposes of this essay, I will use the term “union.”) The group has had three meetings and plans to continue them. I cannot speak for the others who have come together to form this affiliation, but I will detail why I feel very strongly about its necessity and why Occupy is the perfect catalyst for it.

In our meetings there have been two major issues that I believe will shape the form of the organization: compensation equity and mutual aid.

The Art Economy

It is no secret that the art and culture industry is a multimillion (billion?) dollar industry. In The Invisible Dragon, Dave Hickey proposes that art is not bought for money, like a commodity, but rather art is invested in, based on its projected value. The “buyer” is buying insurance in the art’s cultural importance. This is both a beautiful and problematic idea that seems to take the “icky” out of the process, but the reality is that the “art” in question is stuck in an industrialized institution that cannot or will not adapt to art’s expanding size and economy. When the workers at Sotheby’s recently went on strike, it became impossible to ignore the ever-expanding labor force that allows the culture industry to exist in its current form. What a travesty it would be for the entire industry, if all of its economic resources were pooled into speculative bargaining with projected cultural value.

Artists Adam Vuitton and Kate Kershenstein protest outside of the 2011 MOCA Gala, holding signs created by Eve Fowler. Photo: Cake and Eat It.

At some point in my quest for a career in the arts, I convinced myself that this industry, like many others, would have a sort of internship period, where I would work for free, with the figurative promise of eventual employment. I’ve also seen it like a small business, in that “you have to spend money to make money.” Never at any point did I think I would “make money” as an artist, but I thought I could have a humble life, pay my bills, and make artwork. There is a drastic distinction between gaining enormous profit off one’s art (such as the occasional Damien Hirst type) and making a living off it, the latter of which is hard for most people to do, even established artists.

In my opinion, the idea that experience-based, performance-based, or time-based artists should work for free because they are working in traditions that critique capital is absolutely meritless. I’m not asking for a mansion, I’m asking for a roof. I would trade rent for a performance. Somehow, the rent needs to be addressed. In every other industry I’ve encountered, risk is directly related to compensation. Dancers, athletes, circus performers, police officers, etc. are all paid according to their level of experience and bodily risk. So for the life of me, I cannot understand why high-risk performance artists such as Ron Athey, Mary Coble, Mike Kelley, etc. wouldn’t be among the highest paid in the industry.

I don’t know what pay equity in the culture industry looks like yet. I know it should include artists, curators, writers, scholars, teachers, handlers, preparators, janitors, receptionists, etc. I know that whether the art is being traded for cultural “investment,” or bought and sold among the rich to impress each other, or supported through $1,200 Gala tickets and donations that are packaged with “naming opportunities” (such as the BP Grand Entrance at LACMA), the funds certainly aren’t “trickling down” to the very people who are producing and tending to the “culture” in question.

First meeting to discuss the formation of an LA–based art union at Human Resources on November 19, 2011. Carrie Mcilwain, Adam Vuiitton, Adam Overton, Brian Getnick, Jen Hofer, Edith Abeyta. Photo: Cake and Eat It.

Mutually Beneficial Alternatives

In our discussion of what the art union would look like, there were many precedents to consider. There have been artists’ guilds, artists’ unions, artist associations, etc. Canada’s CARFAC, the New York–based W.A.G.E., the Freelancer’s Union, and Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) are all great models for what our union could look like, but what if, in addition to collective bargaining, we helped provide each other with some of the resources that are inflating our overhead and spiritual costs? Not only is there desire for a tool library, a collectively owned truck, studio visits and critiques, printers and facilities, but there is an undeniable community of amazing people who are willing to do everything from helping you build a chicken coop to recommending a job lead. This may sound crazy, but I’m going to put it out there: what if the art union acted as an alternative to the MFA program? It may not provide the break from reality to develop your work for a few years, but it would provide all the other resources, minus the $100,000 of debt.

Why this holistic approach to a material problem? Because it is very much a holistic problem. This is a competitive, opportunistic industry that has us competing over exposure because we’ve been convinced that’s what’s needed to land the “job” (whatever that is) and you need the “job” to survive. If the only thing that comes out of this is community solidarity, then that alone is overdue.

The third meeting at RAID Projects included a "stone soup" style potluck. Photo: Cake and Eat It.

Occupy Equity in Art

Lastly, I want to talk about why I think this is the best possible time to be forming a union. Occupy proposes not that you should join a movement without a leader, but that you should be a leader within that movement. Bertolt Brecht’s famous quote, “Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it,” proposes that the future you are trying to create should employ a method that embodies that future. If we want a future of political signs, marches, and speeches, than that’s what we should do to get it. As the anarcha-feminist collective, Mujeres Creando, wrote on a wall in La Paz, “Be careful with the present that you create because it should look like the future you dream.”

What Occupy has done is acknowledge the importance of art in social change; not just because art is powerful, but because using art forms to shape community creates a future that we want. During the 2007 Climate Camp, activists covered their protective shields with photographs of the faces of climate refugees. Recently Ken Ehrlich gave a workshop at Machine Project in Los Angeles that used book covers on cardboard shields. As artists, we have the tools to shape people’s perception of the event happening right in front of them. Why would the form of our union look like every other union, if our protest looks like art? With Occupy filling the air we breathe, it is now easier than ever to reconstruct the idea of “union” into something that is art, into something that benefits the artist, the art laborer, the institution, and culture.

The next art union meeting will be an informal social gathering. It will take place on January 15, at a time and place TBD. Everyone is welcome to come and discuss what kind of form our organization will take and most importantly, strengthen community. Check our Up The Art Union website for further details.

Christy Roberts is a conceptual artist and activist based in Los Angeles. Her work includes performance and social practice and explores concepts that, like art, create their own culture, tension, joy, and dissonance. She received her MFA from Claremont Graduate University in 2011.