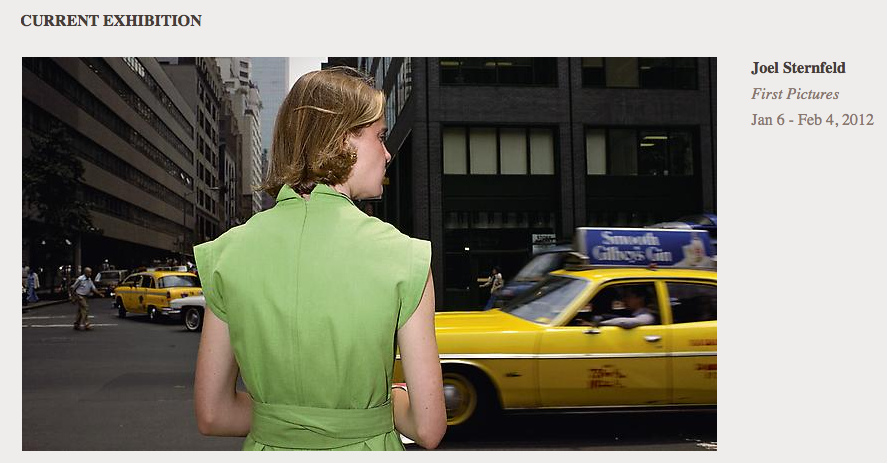

I paid a visit to Luhring Augustine in Chelsea last Thursday night. The reception was for Joel Sternfeld’s First Pictures, an exhibition of four photographic series taken between 1971 and 1980. These photographs demonstrate an early experimentation with subject and color, newly introduced as part of the fine art photography repertoire in the 70s.

Sternfeld’s work is an exploration of human presence and absence in malls, doing chores, at diners, on the beach. The images offer a conversation between the “then” of the 1970s and the “now” of the contemporary observer, psychologies that both overlap and stare unknowingly at one another as shoppers present their purchases to the camera (and us) for inspection in one series, or sun-seekers recline at Nag’s Head in another. In one image, balanced ketchup bottles drip one into another on a restaurant counter like kissing cousins; a woman carries a laundry basket heaving with clothing, an infant sandwiched between it and her belly; a sewage truck is seen through the window of a drab, empty diner.

Emerging around the same time as Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, and other New Color photographers of the 1970s, Sternfeld’s work has always struck me as slightly more straightforwardly engaged with everyday life than that of his peers. Where fellow New Color photographers focused on broad strokes to invoke “the people” or “the place” – the banal and everyday ephemeral existence of life in contemporary America epitomized by Stephen Shore’s roadside pancake stacks and William Eggleston’s iconic tricycle – Sternfeld utilizes detail to underline the specific nature of the spaces he photographs. These images might seem familiar in some sense now. Reality television, and the ability to follow the most intimate and mundane of movements in pictures on social networks, conceal the radical nature of New Color in the 70s – “documents” of all those moments of fleeting, unreconstructed, bare-bones contemporary life. These images had precursors – not least in Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank, to name but a few – but the unashamed use of color, the language of advertising, not fine art, was the shock.

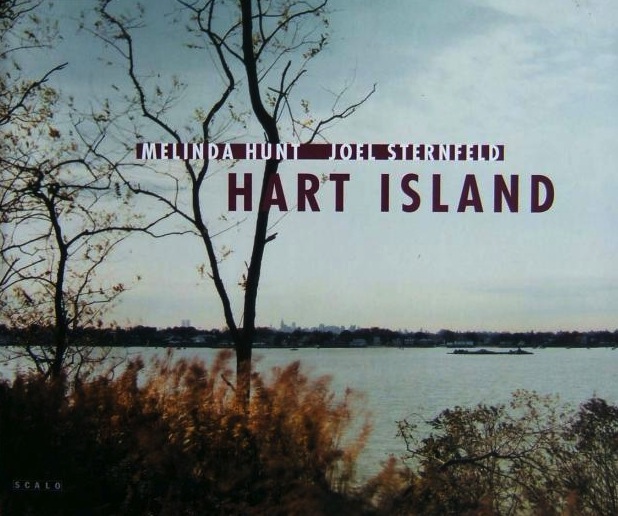

It’s probably important to state my bias: I wrote my M.Phil on Joel Sternfeld’s 1994 Hart Island series, so attending the opening last week was something of a personal homecoming too. I had interviewed Joel in the summer of 2006 when I first arrived in New York and was finishing writing my thesis. I spoke to him on the phone a few years later, and on Thursday I nervously approached him again to say hello. He astonished me by remembering my name (my final dissertation wasn’t great – note to self, never work full-time, move continents, and write 150 pages at the same time) and asked about my current projects. I told him that Hart Island had a large impact on the independent study proposal I was trying to pull together this spring, exploring unseen and peripheral parts of the urban fabric. Indeed, his work has always been the lingering, continuing thread for my academic interests – the underdogs, the individual environmental cogs in the built environment (Sternfeld was a driving force behind the High Line), the unspoken in history. We talked very briefly, he gave me some advice for my bibliography, and then I went home and pulled out his Hart Island series again. Few people seem to know about his photographs of this place, and almost no one in New York seems to know about the history of the island, yet it is in this series I think he most pressingly captures bodies that are usually unseen, hidden, forgotten or derelict. It is here that Sternfeld’s images truly negate the general and the mundane.

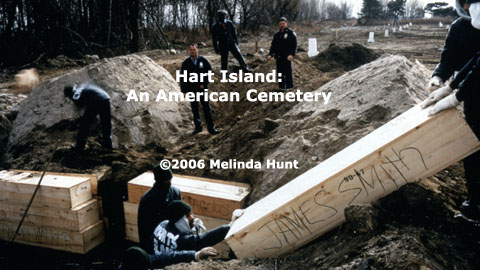

Hart Island is a 40-acre mass of land located off the eastern shores of Manhattan, opposite City Island and the Bronx in Long Island Sound. Currently owned by the Department of Corrections of New York City, the island has been used (among other things) as a prison, a rehab center, an asylum, Nike missile test site, and most continuously for the past 150 years or so, as a potter’s field, an indigent burial ground for the five boroughs of New York City. Four days a week, prisoners from nearby Rikers Island travel on a morgue boat loaded with uniform pine coffins destined for burial in mass graves on the island to bury those who have died unclaimed, from within the city’s hospitals and institutions to its streets. Over a series of three years in the early 1990s Sternfeld traveled on this boat and visited the island, usually on a monthly basis. Hart Island consists of ten introductory collage pieces – photographs bordered by archival burial records, created by Sternfeld’s collaborator on the series, Melinda Hunt – followed by forty-four color photographs. The importance of Hunt’s collage and writing (the text for the book) in relation to Sternfeld’s images is significant and plays a fundamental role in their interpretation. Hunt went on to make a film about the island, Hart Island: An American Cemetery (2008) and has a show of her own currently up through January 14 at Westchester Community College’s Center for the Digital Arts (The Hart Island Project: Shades of New York), and others have kept its legacy alive through documentation, but it’s Sternfeld’s photographs that I keep coming back to.

The main “protagonists” of this place remain either faceless (the coffined dead) or nameless (the prisoners performing the burials) or both (the invisible, decomposing corpses inherent in Sternfeld’s depctions of the island landscape). Even when represented, figures remain inherently fugitive in these landscapes, consumed, decaying or invisible to the city in the background. Hart Island’s initial place on the outer edges of the city suggests not only a geographical “othering,” the movement of cemeteries away from the living. Through representation, Sternfeld acknowledges the distinction between what is recorded in a society’s cultural memory, what is not, and what exists in a state of purgatory, semi-erased. The medium itself – the apparatus of camera-machine, the manipulation of shutter onto light-sensitive material – has long been associated with death. Roland Barthes describes the photograph as a space in which death is confirmed not once, but twice. Referring to “historical photographs” he states, “there is always a defeat of Time in them: that is dead and that is going to die.” As photographer, Sternfeld selects from the multiple strata of Hart Island to create a history for us based on his personal knowledge. His approach to landscape is as a repository of information, soil imbued with cultural memory that is guaranteed an immortality of sorts through the photograph. Each viewing of these images is a metaphorical spreading of ashes. As critic Michael Starenko wrote reviewing a much earlier show of Sternfeld’s work in 1984 (just a few years after the images at Luhring Augustine were shot), “if we as a country were more sensitive, more perceptive, more attentive to the minutia of our cultural landscape, America might be a better place to live, or at least that is what Sternfeld’s work seems to imply.” This seems to be a good phrase to have at the top of my page as I try to pull together a reading list for my independent study, dealing with architecture, everyday urban and suburban landscapes, and forgotten places. Dolores Hayden and Dianne Harris are my touchstones. What else should I add? Suggestions in the comments are very welcome.

Go see the show–open through February 4, 2010 at Luhring Augustine, 531 West 24th Street, New York, NY 10011.