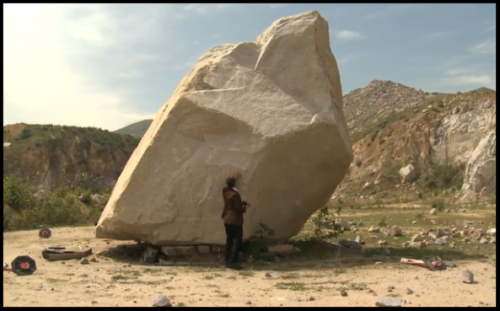

Levitated Mass in progress: Michael Heizer's handpicked granite boulder aboard its custom transporter nears LACMA at 4:30 a.m. Saturday, March 10. Courtesy Gene Blevins, L.A. Daily News.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, if you live in Los Angeles you’ve no doubt been immersed in the buzz around LACMA’s gargantuan effort to install Michael Heizer’s new work, Levitated Mass. I was initially hesitant to add my voice to the chorus of hype (and regrettable rock puns), but it’s hard to resist the gravitational pull of an urban earth art piece of this scale. Moreover, the hype itself bears some analysis. Museums are forever struggling to find ways to “reach” audiences—particularly west of the Hudson River. But this 340-ton rock—the mass that will ultimately appear to levitate above an expansive cement trench on LACMA’s campus—has almost literally woven a thread across the Southland, from the center of LA through the sprawling Inland Empire. Traversing 100 miles of pavement through 22 cities between the quarry in Riverside to LA, the giant stone has created a tremendous spectacle, drawing gaping crowds at every stop along the way. Since the custom-built transporter—the length of a city block and the width of three highway lanes—can only travel at up to 5 mph and occasionally takes up to 2 hours to make a single turn, the rock could only travel under the cover of night. Gawkers could follow the boulder’s progress via LACMA’s twitterstream. During the day, locals spontaneously welcomed the rock to their neighborhoods with Rock Block Parties. As my co-columnist Catherine Wagley reported in LA Weekly, Bixby Knolls even threw an official celebration, dubbed “Rockapalooza.” Over the rock’s 11-day journey, over 20,000 rock fans turned out to ogle it, and over 1,000 cheering night owls and early risers were waiting at LACMA when the rock finally rolled up at 4:30 am on March 11.

Revelers at the Bixby Knolls Rock Block Party in Long Beach. Courtesy Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times.

Of course a large chunk of Levitated Mass’s allure can be attributed to the engineering feat of transporting the monolith. The effort and labor of constructing the work is roughly analogous to the craft demanded of, say, photo-realist painting. I don’t mean to insult “the public,” but certain members of said “public” continue to insult certain forms of painting with the good ol’ “my kid could do that.” And nobody’s kid could make levitated mass. At the same time, Michael Govan’s comparison of Levitated Mass to the herculean monoliths of ancient cultures invites other forms of naysaying. For instance, a commenter on LACMA’s youtube channel scoffs, “Meh…The Egyptians moved 200-450+ ton solid obelisks from their quarries along the Nile to their cities. The Romans then managed to move these same solid 200-450+ obelisks from Egypt across the Med. Sea to Rome. All with ancient technology.” Indeed, JamesSOCO2006, all of Chichen Itza was built without the aid of a wheel, and yet Levitated Mass required a truck with nearly 200 wheels. But none of us were alive to see that happen, and while we have more advanced technology, we have since renounced slave labor.

LACMA director Michael Govan with the rock at its origin in Riverside, CA. Courtesy LACMA.

The more popular dissenting view is one commonly levied against grand public works, pointing to the $10 million cost of creating Levitated Mass. Defenders of expensive installations typically point to costlier public efforts—for example in 2011, the Iraq War cost us roughly $10 million every 2 hours. Moreover, in the case of Levitated Mass, the funds were raised from private donors rather than using precious taxpayer dollars—although that is not always the case for public art projects.

When I visited Levitated Mass once it was unloaded at LACMA, my friend kept marveling at how disappointingly small the rock seemed. For all the controversy and buzz, he found the giant stone to be anticlimactic, and kept comparing it to Southern California’s famous boulder, known as Giant Rock. Indeed the latter, located in Landers, CA, towers at 7 stories–more than three times the size of Heizer’s 2-story hunk of granite. And while nobody, to our knowledge, has attempted to move Giant Rock, Frank Critzer famously excavated an entire multi-room home beneath the boulder and lived in the space through 1930s and early 40s. Floating precariously above Critzer’s makeshift basement dwelling, Giant Rock must have had the same levitating appearance that Heizer is now attempting.

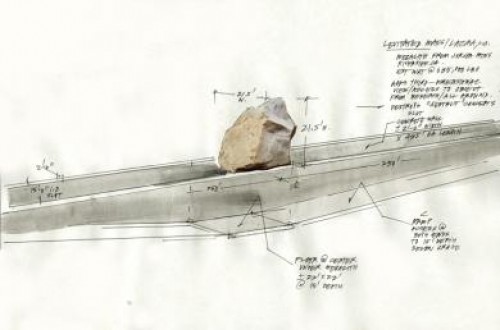

Michael Heizer's drawing for Levitated Mass. Courtesy LACMA.

Yet for every naysayer, there seem to be a dozen proponents of Levitated Mass. In his LA Times discussion of the piece’s progression, Christopher Knight asserts that our culture tends to view art as female, and perhaps as a counterweight to the possibly misogynistic maligning of public art, LACMA has undertaken a decidedly macho effort with Levitated Mass. Although Knight concludes his article with a puzzling jab at Ms. Magazine, he astutely notes that LACMA has commissioned large scale outdoor works by exclusively male artists. Certainly, the most recognized producers of large-scale scultpture are men, with exceptions such as Louise Nevelson, Nancy Rubins, and Louise Bourgeois (Season 1 of Art in the Twenty-First Century). Moreover, save for artists like Maya Lin (also Season 1), Nancy Holt, and Jean-Claude (though inextricably linked to her male partner Cristo), land art has been a particularly masculine purview.

Michael Heizer, the proto-Burner. In 1968, he created "Dissipate" in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada--now home to hundreds of grand installations each year during Burning Man. Courtesy Portlandart.net.

As a female painter, I am vaguely aware of the art world’s vestigial sexism. During my days as an undergraduate art major and college art professor, my studio classes had always been populated almost exclusively by young women. Yet in graduate school and in the art world, the ratio seems to switch—often leaving me to wonder where all these male artists come from, and what happens to all the women art majors. Moreover, perhaps the fact that I so easily stayed in the realm of painting (Heizer started as a painter)—rather than more physical or technological forms of media–is of significance. My mind keeps returning to Virgina Woolf’s essay A Room of One’s Own, in which she attributes history’s lack of women writers, in part, to their historical lack of personal, private space. While it’s now much easier for women to find rooms and studios of our own, perhaps it remains more difficult for women to access public spaces for executing large scale works—either through lack of trying or lack of support.

The fact that the rock has people talking—about gender, the ways we choose to spend money, the possibilities of modern engineering—seems valuable. Meanwhile, the 40 year journey of Levitated Mass remains to be completed. We will have to wait until LACMA’s custom 300-foot high crane drops the rock into place atop the 456-foot long trench before we can experience the finished work—and decide if it lives up to the hype.

The ramp that Levitated Mass viewers will traverse. They will look up to see the famous rock levitating above them. Courtesy LA Curbed.com.