Well, it’s done. I am a Master(ess) of Arts. (Unofficially, though, since I won’t receive my diploma until I put the finishing touches on my thesis and submit it to the library.) Now for the hard part.

The great risk of going to grad school is the possibility that several years down the road, you will find yourself with another piece of paper and no better idea of how to gain entry into and function within the professional world. Luckily, I don’t doubt for a minute that pursuing an advanced degree was the right choice for me. I feel much better equipped to begin a career as a cultural worker than I did two years ago. Still, I worry that sustaining my current level of passion for issues in my chosen field will become increasingly difficult as the pressures of getting a job and figuring out the rest of my life intensify.

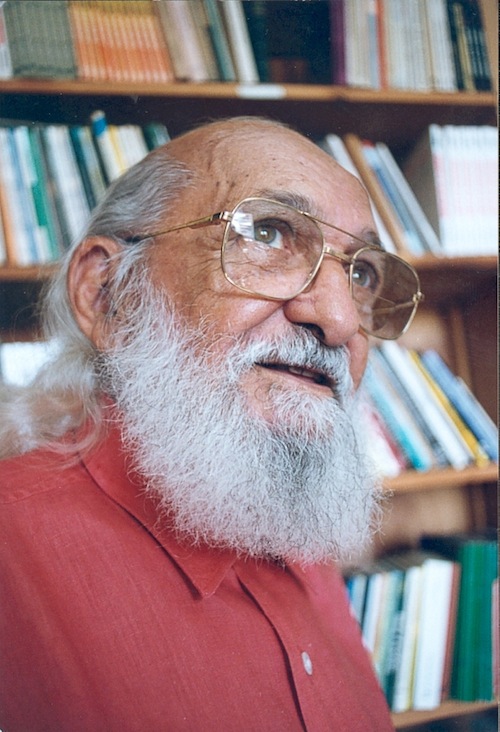

In my last post, I wrote about my interest in dialogue, and discussed it in relationship to contemporary art, literature, and museum practice. I neglected to mention Paulo Freire, the scholar who is perhaps the most provocative theorist of dialogue. Freire, a Brazilian educator and author who died in 1997, is something of an icon in my social justice-focused art education program. Part of my reluctance to talk about his work is my conviction that I cannot do proper justice to its eloquence and meaning.

In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire refers to dialogue as “an existential necessity,” and “the way by which men achieve significance as men.” He further explains:

Dialogue is the encounter between men, mediated by the world, in order to name the world. Hence, dialogue cannot occur between those who want to name the world and those who do not wish this naming – between those who deny other men the right to speak their word and those whose right to speak has been denied them. (Excerpts from Paulo Freire, 1970, pp. 75-86)

This naming of the world through dialogue, Freire warns, cannot transpire “in the absence of a profound love for the world and for men.”

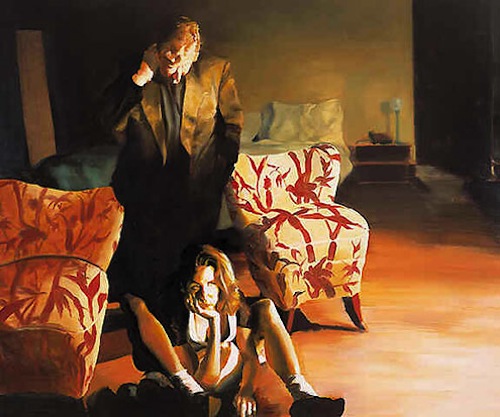

This part, I think – about the purpose of dialogue and its relationship to love – is fairly easy to grasp. It’s also something that I often catch allusions to when I listen to artists talk about their motivations and intent. Near the end of his commencement address at my school the weekend before last, the figurative painter Eric Fischl said: “I paint to show myself to myself, and ultimately, to show myself in relationship to you.” Is this not an act of naming the world?

In a talk I attended earlier this month at the Art Institute of Chicago, the photographer Dawoud Bey said his job was to get people to perform themselves in front of his camera – indeed, to get them to perform the best version of themselves. If Fischl is thinking about his artmaking as an initiation of visual dialogue, then Bey, it seems, is thinking about the artistic process as an entire dialogue. His request to photograph a person is an extension of love to the subject, an affirmation of their “right to speak,” and an invitation to name the world together.

Returning to Pedagogy of the Oppressed, I am confronted with the more complicated, and most crucial, part of Freire’s argument. In it, he identifies “the essence of dialogue itself: the word,” and proclaims that the word must be authentic. An authentic word, to Freire, consists of equal parts reflection and action.

Freire discusses the danger of the word that is all action and no reflection, but it is what he writes about the all-reflection, no-action word that lingers in my mind:

When a word is deprived of its dimension of action, reflection automatically suffers as well; and the word is changed into idle chatter, into verbalism, into an alienated and alienating “blah.” It becomes an empty word, one which cannot denounce the world, for denunciation is impossible without a commitment to transform, and there is no transformation without action. (Excerpts from Paulo Freire, 1970, pp. 75-86).

Here is what I want to say to my fellow graduates, and to all educators, thinkers, and citizens: let us not forget Freire’s caution. We must continue to write, and to talk, and to work toward naming the world, but we must not lapse into verbalism. We must do everything we can to avoid the alienating “blah.” I am not yet sure what this will entail, but I think we can figure it out along the way.