I was certain dusk had arrived too soon. It was the last week in May, and I had woken from my nap at five in the afternoon to find nightfall when the evening before the light had lingered until seven. I texted a friend: “It got dark so early today.” He did not write me back. I was beset by a cold and staying at my mother’s house in the Sierra Nevada, at an elevation of six thousand feet. I felt feverish.

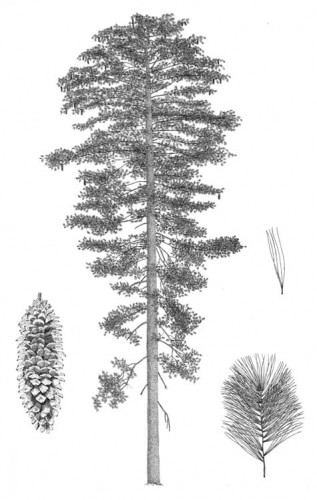

A sugar pine. Illustration by Aljos Farjon. Image source: https://www.conifers.org/

I went outside, hoping to solve the mystery my waking had initiated. I walked behind the house, down a hillside covered with Manzanita and sagebrush. Lodge pole and sugar pines stood overhead. All was dim, as though the sun had paused in its setting. I walked along a trail barely carved through the brush. With eyes failing and light waning, I squinted. I looked closely: tree trunks embroidered with insect carvings; gobs of pine tar, campfire-scented, stuck to their sides. Mule’s ears flopped by my feet.

Image source: Flickr user fksr.

Then a tree of light, each branch shaped like a crescent moon, flickered on the dirt before me. The ratio of dark to light seemed reversed, as though shadow were being projected rather than sun. I turned to see what new piece of the forest had created this shape, but I saw only the drooping branches of a Sierra juniper. A reconfiguration had been made in the sky, it seemed, and the results danced on the ground by my feet.

The distorted shadows reminded me of the work of Chris Fraser, a Bay Area artist. Fraser’s handmade apertures channel ambient light into immaterial sculptures of white, black, and gray. By manipulating openings, Fraser amplifies the ongoing and ever-present negotiation between light and dark.

Chris Fraser, "Light Drawing," 2011.

In Light Drawing, a 2011 installation at Oakland’s Pro Arts Gallery, light enters an enclosed space in rays of gradated thicknesses and intensities, resulting in a spectrum of tonal relations. At the edge of the projection, the beams are starkly distinguished: white beside black. Toward the center, the distance between the two shades lessens. Triangles of white transition into gray shards; mid-range shadows gradually become darker as they fan out into black. Presented in this way, as a series of measured steps, the journey from light to dark does not seem so far or so daunting.

As I walked along the trail, I thought about Fraser’s work, and I wondered what sort of nap could’ve delivered me into this inexplicable dusk. Lacking explanations, I was forced to dwell in indeterminacy. My inquiry became experiential: I investigated shadows on the ground, parsed leaves on trees, and considered the sun for what felt like the first time.

Google Goggles interprets Frida Kahlo's Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931; oil on canvas). Image source: https://icoblog.wordpress.com/2011/02/16/google-goggles-search-by-sight/.

In an oftentimes predetermined world, such inconclusiveness is a rare luxury. That same week a friend had told me about Google Goggles, a mobile app that feeds you data based on your encounters with visual phenomena. Such a stream all but negates the moment between encounter and interpretation. It allows us to elide the intermediate space between our introduction to stimulus and our inventorying of it. This is unfortunate, for it’s there that meaning is unformed, malleable, and full of potential.

Fraser’s work also inhabits this intermediary space. Though it’s possible to consider his work in the context of work by California Light and Space artists, the artist situates his practice within a photographic legacy. His work molds light “not to offer up a philosophical or spiritual meditation on perception, but rather to remake our relationship to the camera, and to the everyday production of images,” writes Erica Levin in her catalogue essay accompanying Fraser’s 2011 Pro Arts piece. His installations “place the viewer inside the camera, between aperture and blank surface.”

Chris Fraser, Light Drawing, 2011.

In a world overpopulated with images, in which our responses can become calcified and reflexive, Fraser’s light sculptures pause at the moment prior to interpretation. By intervening there, in between light’s projection and its solidification into image, the artist suggests the possibility of new visions.

When I returned to the house, my phone blinked on the nightstand. An explanation had arrived: “Look up!” my friend wrote. “It’s an eclipse.” With one word, the mystery dissolved. I was grateful it lasted as long as it had.