I heard that Western and Eastern medicinal practice split apart with dissection. While the Eastern approach treats a holistic body, whereby each component is connected and influenced by another, the Westerners began to exhume cadavers to identify each interior part. Much of Terri Kapsalis’ work lies at the heart of that divergence: she investigates the insides and outsides of bodies as well as the means by which conclusions about the body are drawn. To leave her interest at that, however, would be too clean and succinct. She is also a performer, and a writer. She investigates the history of sound and music, and yet, in every instance pokes at the methods of communication and authority. With a special advantage as an artist, she poses critical light on common fields, exposing the most captivating and mythical aspects of that landscape. Kapsalis has published such works as Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum (Duke University Press) and The Hysterical Alphabet (WhiteWalls).

"Hortensia," drawing by Gina Litherland with text by Terri Kapsalis, excerpted page from The Hysterical Alphabet, published by WhiteWalls, 2008.

Caroline Picard: Can you talk about the role of research in your practice? I was thinking particularly of the museum label you created for the Hull House’s display of Jane Addams’ travelling medicine kit and your Victorian-style children’s book, The Hysterical Alphabet. In both instances, the final, public result points back to a phenomenal amount of research. What is that process like for you? How do you create a public conclusion?

Terri Kapsalis: I’m so glad that that is evident for you in the work. I love bathing in research. Take a long soak, let the mind wander, and then see what comes of it. For me, research is an antidote to what the Oulipans call “the tyranny of inspiration.” I thought that my research on the medical diagnosis of hysteria would result in an academic reader, a volume of primary medical writings collected from across hysteria’s 4,000 year history. After a good deal of thought, I realized that I was much more interested in making something new with the wild metaphors and ideas I encountered. The Hysterical Alphabet began as a way to get my head around that enormous history. I have a poor memory so I thought a timeline would help. Timeline led to alphabet, alphabet led to Victorian children’s alphabet book, and so on. I would immerse myself in materials on Ancient Egyptian ideas of hysteria, for instance, and then work those ideas into the condensed, fictional case studies that became the letters A and B of the alphabet. I worked in chronological order and the entire process took more than six years for what ended up being a very small book. All along, conversations with my collaborator, artist Gina Litherland, were key. In the end, it was very clear to me that I needed to include a bibliography. Some material in the book is so outlandish it seems like it might be fiction, yet it is all pulled directly from medical history. Isn’t that an appropriate way to handle such medical “facts”? Make them fiction.

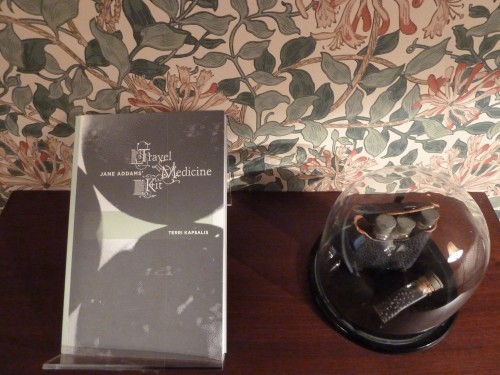

Including a bibliography was also important to me with the Addams’ travel medicine kit project. I was commissioned by Lisa Lee at the Hull House Museum to create an “alternative label” for this small leather medicine kit on display at the museum. I am by no means an Addams scholar and there are many out there. But I had done those years of research on hysteria and, early on in my medicine kit research, I was amazed to discover that Addams had been treated by S.Weir Mitchell, the very physician who treated Charlotte Perkins Gilman. This sent me to Gilman’s and Addams’ archives and writings. At the beginning of the process, I had convinced myself that I didn’t need to know what was actually in the four vials of pills and powder in Addams’ kit in order to write my essay, but then half-way through the process, it became clear to me that knowing was important. And luckily, the University affiliated with the museum has a forensics program with faculty and a grad student who were excited to analyze the kit. Observing their research allowed me to address yet another body of questions.

Jane Addams' Travel Medicine Kit and Terri Kapsalis' Alternative Label at The Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, 2011. Photo: Rachel Glass.

Throughout the research for the medicine kit essay, I was thinking about the short form of the museum label and, in response to the research, writing all of these short bits on various thoughts and discoveries, including bits related to Addams’ health history, her relationship with Gilman, the analysis of the kit, and so on. In the end I found a large piece of cardboard, cut up all my short bits into discrete pieces of paper, and began to arrange them with push pins. After the essay was finished, I remembered having read that Addams would string a clothesline in her office and clip her notes across the line with clothespins, rearranging them over and over again, soliciting others’ input, until the shape of her essay would appear. I was pleased to have backed my way into Addams’ working method without even realizing it.

Both The Hysterical Alphabet and Jane Addams’ Travel Medicine Kit exist in book form while also having other public lives. Jane Addams’ Travel Medicine Kit is installed in Addams’ bedroom next to the actual kit. People can sign up on the Hull House Museum’s website for an appointment to sit in Addams’ bedroom with the essay and be served tea. I am thrilled to have the opportunity to have this kind of interface with a public space, especially such a magical one. In addition to its book form with drawings by Gina Litherland, The Hysterical Alphabet has had a life as a performance comprised of film with live soundtrack. Collaborators John Corbett, Danny Thompson and I have toured the piece to a number of universities, including Emory, Bates, Clark, and RISD. The performance has a very different feel and aesthetic than the book, but the text is nearly identical. We last performed the piece in November 2011 at the Art Institute of Chicago’s Fullerton Hall. We said it was our last performance, but apparently, we lied. Following that performance, we were offered the opportunity to perform the piece at the new Logan Arts Center in Hyde Park as part of University of Chicago’s Arts/Science Initiative. We’re set to do that in November 2012.

Writing is such a solitary act. It is great to have the opportunity to share words in public ways.

CP: I almost feel like you reanimate histories and like learning the history of hysteria could have a medicinal quality, almost… How do you negotiate history in the present?

TK: That’s great. “Learning the history of hysteria has a medicinal quality.” I completely agree. I teach a course at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago titled “Wandering Uterus: Journeys through Gender and Medicine.” The first three weeks or so of the course are an investigation of the history of hysteria. From there we look at everything from the history of gynecological experimentation on slave women to the history and politics of birth control to health care for LGBTI folks to ideas about sexual dysfunction and so on. Beginning the course with the history of hysteria offers a lens for understanding where we are now. What are we playing into, what are we resisting, where do our rules come from? The “Wandering Uterus” has gained a kind of cult status. I have students writing me or stopping me on the street and asking me when I’m teaching it next. There is an appetite for this material. When you read some of the dark historical stuff – for example, clitoridectomy as “treatment” for mental illness in the 19th century – it’s hard not to get completely disheartened. Another option is to live in the we’re-past-that-now delusion. I am not interested in inspiring bitterness or antagonism. Rather, I think of this material as an important cultural legacy to understand so that we can investigate the assumptions we’re dealing with.

CP: How did you find your way into the study of medicine?

TK: I helped pay for graduate school in Performance Studies at Northwestern University by working as a gynecology teaching associate, teaching medical students breast and pelvic exams using my body as a teaching tool. It was some of the most challenging and political work I’ve ever done. One Saturday, I wanted to attend a Performance Studies conference but I had committed to teaching at the medical school. In the middle of the teaching session, with students shifting the exam light and vying for a look at my cervix, a light bulb went off in my head: Okay, this is performance! That was the start of my book, Public Privates. For twenty-one years and counting, I’ve also been a health educator at Chicago Women’s Health Center. At one point, I thought of becoming a physician, but then realized I was more interested in non-allopathic modalities, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Following the publication of Public Privates I apprenticed with a sixth-generation Chinese physician for three years and realized the ideas interested me more than becoming a practitioner. In TCM, the relationship between the body, mind, and emotions exist in a different paradigm, and I’m sure that this understanding has impacted my writing and thinking on hysteria.

In graduate school, I was very moved by Donna Haraway’s writings on science as fiction. She says that as long as we’re using language, we’re enlisting narrative. Science, including medicine, is not exempt from storytelling. Medicine has traditionally been sacrosanct. We’re taught not to question it. Writing about contemporary medical practice when I’m not a physician or nurse has pressed some buttons, at times, but why shouldn’t somebody who thinks a lot about performance and power have something to say about gynecology? It makes complete sense to me.

CP: I came across a re-enactment you gave of John Cage’s “Lecture on Nothing” at the Renaissance Society a few years ago. How does sound fit into the work you’re doing?

TK: I think about words as sound, as language spoken aloud. I started acting in plays when I was in grade school. I’m a founding member of Theater Oobleck and have been working with many of the current members since 1984. Some of my earliest writing was designed for performance. I also played classical violin as a kid and continued as an improviser in my twenties and thirties, when I had the opportunity to play with a number of incredible musicians, like Mats Gustafsson, Tony Conrad, Thurston Moore, and the great Japanese noise singer Junko. Performing Cage’s “Lecture on Nothing” felt like a natural extension of these interests.

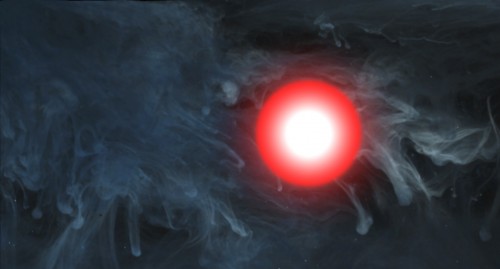

Collaborating with sound artists and musicians is a different kind of nourishment from my research-based work. The recent opportunity to collaborate with Damon Locks and Wayne Montana of The Eternals on this soundtrack for the video Noon Moons was a purely enjoyable combination of the two. Damon and I had been commissioned by Experimental Sound Studio to make work enlisting the Sun Ra audio archives and we decided to work together and bring in Wayne. Portland-based animator Rob Shaw made a striking visual accompaniment for our soundtrack. Sun Ra understood the power of language. Listening to him read aloud or talk or lecture is like listening to music. I’m a long-term Ra fan and, thanks to John Corbett, I have dug deeply into Ra’s extraordinary Myth-Science omniverse. That’s a long story, and a good one.

Still from "Noon Moons" (18 min.), animation by Rob Shaw, soundtrack by Terri Kapsalis and The Eternals, 2012.

I wear a number of hats and certain things I make or do don’t make much sense in proximity to other things I make or do – sound and health education, for instance. I used to feel like I needed to have some kind of overarching personal mission statement, but I no longer believe that. Some of the things I do play nicely together and they are integrated. Others are separate. Differing impulses often reside within a single person. An individual doesn’t need to be a unified field theory.

Pingback: New Interview with Terri Kapsalis | The Lantern Daily