My contribution to the Ideas issue, The Culture Wars, Redux, was an essay about the ongoing crisis of representation in cultural institutions. I noted cultural critic Vijay Prashad, who advocates for a polyculturalism which views the world as “constituted by the interchange of cultural forms.” This addendum to my original essay highlights artists who represent a junction of ideas and concepts, use different materials that permits culture to move from one form into another, and invite engagement through multiple modes of discourse. Many second and third-generation postmodernists have overlooked these intersections, especially ones that have some bearing on contemporary considerations of race and gender in art. As a social construction, this development encourages us to negotiate, or stabilize, the meanings of their work. As they relate to creative practices, these are the major tracks and themes I will explore here:

Syncretism is defined as the collision or reconciliation of disparate beliefs, systems of thought and forms of expression. It has become associated with representations and belief systems that reflect the myriad of African, Amerindian, European, Asian and North American cultures from which they emerged. Here, this incorporation has allowed for a kind of covert resistance and a rich mixture of associations between representations and a variety of techniques and media. This term is closely related to bricolage or making do with whatever materials are on hand.

Black (native) vernacular technological creativity frames language that defines a relevant social group as a fluid assemblage of individuals who share a common meaning of an artifact. It opens up interpretive flexibility to acknowledge and consider a multitude of coexisting technological meanings for a variety of social groups, and creates an opportunity to study how African Americans, and other marginalized peoples, create their own relevant social groups that decide which technologies work for them and how to use them.

Polyculturalist artists use their work to project or augment (overlay) aspects of their awareness that may intentionally undermine the illusory or fantasy aspects of their narratives, encouraging more critical views of their work. This projected self seeks to become a primary identity, demanding to be acknowledged and included. Awareness of immersion in the sociocultural realm has led postmodern artists to create work that either invites themselves, or their audiences to reflexively examine their own position in relation to the artwork in physical or virtual space and in the artwork’s institutional context.

Mark Bradford. Mirtha, 2008. Artwork (c) Mark Bradford; Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York/William Wilson. Kiyaaaanii Nishli, 1997. Artwork (c) William Wilson; Courtesy of the artist/Vanessa Maia Ramos-Velasquez. “Digital Anthropophagy and the Anthropophagic Re- Manifesto for the Digital Age,” 2011. Photo courtesy the artist.

We want more than your whites and blacks brought from far away lands, give us thine colorful data from the virtual worlds. – Vanessa Maia Ramos-Velasquez

I first encountered Vanessa Maia Ramos-Velasquez during her presentation at ISEA2012 in Istanbul. Vanessa’s thesis, Digital Anthropophagy, offers a new take on cultural cannibalism in the digital age. In this work the Brazilian artist recasts archetypal savages as “surpassing their own limitations by reaching outside of the self and assimilating and acquiring the qualities of ‘the other.’” When she makes reference to “colorful data” she invokes a postmodern, polyculturalist vision to produce new knowledge that serves as a basis for change. New media art can represent this knowledge in innovative ways, especially by making viewers aware of different social conditions and by immersing viewers in the work. Rather than be distanced from this artwork, they are implicated in it.

In the Anthropophagic Re-Manifesto for the Digital Age Vanessa Ramos-Velasquez recites her texts and engages the audience in the practice of “consumption (ingestion, digestion and excretion) involving a technological mediation,” where participants are invited to tear off and eat portions of texts written in black permanent marker on rice paper – a symbolic Eucharist. She seeks to update the anthropophagic practice of cultural cannibalism – mostly online or virtually – where anyone can be a colonizer. This ritual, recast in a positive light, no longer exists just to protect the physical body – the acculturation results from interaction and immersion in the work.

In 2010, Ramos-Velasquez dedicated her performance to the Afro-Brazilian Goddess Yemanjá (Yemonja) who is synthesized from African, Amerindian, and European belief systems and syncretized with other deities. In Yorùbá belief Yemoja means “yeye emo eja,” or “mother whose children are like fish” which represents the vastness of motherhood: the woman’s fecundity and reign over all living things. As many Brazilian religious (Umbanda) practitioners send their gifts to Yemanjá in wooden toy boats, Ramos-Velasquez was inspired to use Skype to make contact with a Yorubá spiritual center in Brazil to ask for their blessing to put the boat in the virtual sea (here, with video of the ocean recorded in Rio de Janeiro).

Scholar Roy Ascott writes that syncretism is an attempt to “reconcile and analogise” disparate religious/spiritual and cultural practices in disciplines such as art, and may contribute to our understanding of multi-layered worldviews – material and metaphysical – that are emerging with our engagement in, amongst other things, ubiquitous and creative technologies. Rayvon Fouché describes black vernacular technological creative acts in three ways:

These representations demonstrate multiple ways that African Americans and Indigenous people as culturally and historically constituted subjects have engaged the material reality of technology in the Americas and beyond. Artist/filmmaker Cauleen Smith gave me more words to “analogize” this kind of work: “hybridity, trans temporal, collage, recycle, mélange, appropriation, hotchpotch, leapfrog, the tether, the loop, synergy, hand-made, bricolage, improvisation, mongrelisation, margin, void and transculturation.” Another word I honed in on was “ethos,” or “spirit of the times.” Author Leonard Shlain argued that the visionary artist is the first member of a culture to see the world in a new way. Shlain showed how the artists’ images, when superimposed on other concepts, create a compelling fit. I consider the artists highlighted here, and whose stars are on the rise, to be polycultural visionaries.

Contemporary artists use technology and consciousness to explore new subjectivities within frameworks of culture, history, hyperrealism and global awareness. Camille Norment describes Swing Low as “an audio sculpture work based on the old Negro spiritual, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The song serves as inspiration for Norment’s “multi-channel sound focusing system in which audio samples swing back and forth across the room like a pendulum–or lynch rope.” These audio samples, representing the disembodied phantoms of violent acts, engage listeners as subjects in a historical narrative and can only be heard while the body of the listener is physically present within the “zone” of the sample. Here, multimodal technologies enable forms of syncretism and cultural production that immerse audiences in specific contexts. These forms are as applicable to syncretic references as they are to material installation, performance, and open source works on the web, or in virtual worlds. One of Norment’s recent works is Within the Toll (2011), an 8-channel permanent outdoor sound installation in Norway.

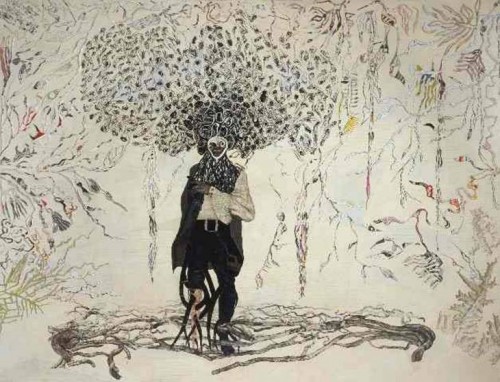

Sanford Biggers refers to syncretism, among other themes in his work. In Blossom he programmed a player piano to perform his original arrangement of the American jazz standard Strange Fruit.

Last week I visited Sanford Biggers’ studio to see his works-in-progress. Earlier, when I asked Sanford which pieces he thought I should focus on, he told me about his re-purposed quilts. This led to as series of blog posts covering this development. Sanford is a musician, so in his work music and sound figures in as well as sacred geometry and science-fiction. His new work visualizes five harmonic scale patterns, or more specifically the perfect fifth that, according to Hermann von Helmholtz, is “found in all the musical scales known.” In a previous Art21 blog post (re: Codex) I write about Sanford’s use of motifs such as simulating a central geometric image created by a harmonograph, or apparatus that employs pendulums to draw. The harmonograph motif and quilt was on view in the The Cartographer’s Conundrum exhibition at Mass MoCA and has been acquired by the Miami Art Museum.

Sacred geometry (geometric design) and raw cotton “clouds” figure into his work, as seen in another quilt I saw him working on this week. Here, you can see Julie Mehretu‘s influence, as well as other motifs seen in Codex such as Lotus, Biggers’ “highly stylized,” twenty-four-petal filigree pattern in the shape of a flower.

The individual units that make up the interlaced pattern are schematically rendered bodies place side by side. The shape of each elongated petal and the configuration of bodies within it correspond to a particular eighteenth-century diagram: that historical image that shows the layout of the tightly packed human cargo holds of slave ships crossing the Atlantic from Africa to America, what is called the Middle Passage of the triangular trade route that also included Europe. [Eugenie Tsai 2011]

Sanford showed me Lotus printed in red on a piece of muslin cloth, and for the first time the whole pattern has been sewn directly onto his work, rather than appliquéd or painted on, or etched into glass-like material.

Rayvon Fouché argues that, historically, technology has been a potent form of power in material form that has politically, socially, and intellectually silenced black (and Indigenous) Americans, and in the worst cases rendered them defenseless and invisible. However, as demonstrated above, artists have appropriated the material and symbolic power and energy of technology in their work. Sanford is planning to continue exploring hip-hop in a music-based performance piece involving several DJs. This intersects with the sociopolitical significance of hiphop’s engagement with technology. As it relates to the themes explored here, there exists enough states of a medium to create a sense of a continuum of possibilities. The sensations of these states become unified through many iterations of “making” or craft. Artists create density (of forms, artifacts, etc.) and coax a variety of materials into new technological platforms and representations. As these condition accumulate, i.e. in works by artists like Rashid Johnson, Mark Bradford, Ellen Gallagher, Auriea Harvey, Pamela Jennings, Paul D. Miller (DJ Spooky), Camille Norment, Philip Mallory Jones, Torkwase Dyson, Mendi + Keith Obadike, and others, it extends discourse in the ongoing process of travel and exchange. By studying this particular domain of artwork, practices, and knowledge, these works will become (or remain) visible metaphorically and materially. Although this is difficult to document, the importance of continuity to reflective, masterful processes cannot be underestimated.

Pingback: Sanford Biggers Studio Visit in NYC « SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: Hank Willis Thomas: Believe It. | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Hank Willis Thomas: Believe It. | Uber Patrol - The Definitive Cool Guide

Pingback: Coded Narratives & Sanfoka Science: New Participatory Design Methods | SL Art HUD Blog Thingie: