I steal catalogs from my neighbors. I know it’s wrong but I can’t stop. The mailman delivers them to a table in the building lobby, and late at night I walk into the brightly lit room and grab them. I try to act casual, as though I’m picking up my own mail. It’s plausible—catalog rosters aren’t the most exclusive of lists, and it’s conceivable that I could find myself on one. But it’s unlikely. To receive catalogs, one must buy from catalogs, and that’s something I do not do. This is in part because I have no disposable income, but it’s also because I am less interested in the objects catalogs sell than in the stories they tell. Catalogs weave elaborate fantasy worlds around desirable objects. Across their glossy pages, products not only perform physical functions—can openers open cans, shoes protect feet—they perform ideas and identities. For someone interested in visual culture and aesthetics, catalogs provide endless fodder.

One of Garnet Hill's autumn 2012 looks.

In the pages of Garnet Hill, a women’s clothing and home décor brand, cunning and lithe white women travel to European countries in jersey-knit dresses being sold for $78. Though not locals, the women are integrated into various foreign settings. Mischievous interlopers, they cart mysterious parcels on the backs of their bicycles. In Athleta, purveyor of women’s athletic wear, blondes with six-pack abs wear supportive bikinis, surf board under arm, as they storm into the sea. A short blurb shares their name, vocation, and life goals, inviting us to see their personalities beneath their sun-kissed, sporty appearances. In the catalog for L.L. Bean, a one-hundred-year-old Maine company that originally sold hunting supplies, an empty pair of slippers and a blanket abut a wool-braided rug being sold for $479—quality goods mean quality downtime.

Athleta models exercise as they pose.

In all of these scenarios, products are placed within deliberately crafted contexts, becoming physical signifiers of the cultural attitudes, lifestyles, and positions on display. Garnet Hill clothing comes to represent worldliness and sophisticated travel. Athleta sportswear is equated with women who are not only fit but self-actualized. L.L. Bean products symbolize downtime spent with loved ones. In these convincing tableaux products become values and vice versa, until the two are indistinguishable. The commodity is twofold, so much so that the shopper may wonder: is it the product or the accompanying identity they buy when they place their order?

Toms shoes, classic model: Kinda boring looking, actually.

The other night, while browsing the mail in my apartment lobby, I found a catalog addressed to a fourth-floor resident I couldn’t resist. On its cover is a South American mountain range, its peak covered with clouds. At the bottom of the photograph is a knit patterned hat and two raised arms holding a simple flag reading “TOMS.” The flag refers to the brand of colorful canvas shoes, the purchase of which funds the donation of another pair to children in need around the world. Unlike other brands that create storylines meant to evoke intangible qualities, Toms connects its product with a veritable action: when you buy a pair of shoes, they give a pair away to children in need. The product’s relatively simple construction underscores this emphasis on giving—its modest, arguably unattractive, appearance invokes the humility of the charitable act it represents.

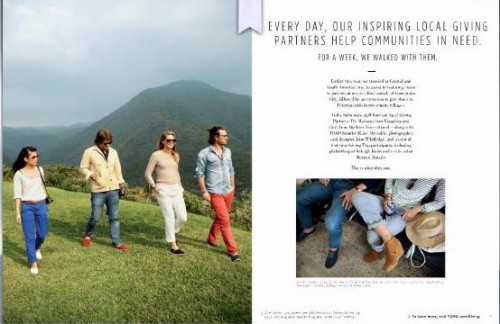

Thirty of the catalog’s fifty pages chronicle a trip in which four Toms affiliates, including the company’s founder, Blake Mycoskie, travel to Guatemala and Peru to distribute shoes to children in remote villages. Its images visually delineate between those who wear Toms as trendy slip-ons and those who receive them as necessities. In stark contrast to the recipients, the Toms representatives resemble visitors from a J.Crew catalog. The catalog focuses on their heroism, and captions are meant to impress with the extent of their generosity: “Each pair of shoes were held together by a rubber band—you could tell how many pairs you had given out by the number of bands you had. By the end of the day, each of us had bands all the way up our arms.” Though annoyingly self-congratulatory, the catalog’s focus shrewdly appeals to the brand’s customer niche: the globally aware consumer who wants their fashion to be altruistic.

New Vans style for fall 2012.

New Toms style for fall 2012.

But when fashion becomes altruistic, altruism is reduced to a fashionable appearance. Toms shoes come to visually signify a charitable act, and as this aesthetic grows more pronounced, other retailers mimic the shoes’ looks. Companies like Vans offer aesthetically comparable products that lack the altruistic undergirding of the Toms brand. Such copies exploit the connotations of the latter’s charitable model, resulting in two visually similar shoes that have vastly different meanings. This strikes me as the danger inherent in aestheticization: signifiers that become detached from their original meanings to float unmoored within our culture of images, vulnerable to endless appropriation and misuse.