Artist Jen Mazza’s practice borders on obsolescence: oil painting. To push herself closer to the edge, she is a representational painter, depicting ordinary objects: slabs of flesh, flowers and chintz, and most recently, books. As it is for most artists, the life of a painter isn’t an easy one, and Jen has faced and overcome her share of hardships. When the global financial meltdown hit in 2009, its reach extended to Jen’s studio practice. Our interview discusses how she dealt with the crises’ impact on her studio, how she showed up one day at a time in the studio, and ultimately landed her first solo exhibition at Stephan Stoyanov Gallery in the Lower East Side. This is a story of one artist’s Spartan, hand-to-mouth existence, and how it has begun to pay dividends.

BC: What type of work do you create, and why? As you make the work, do you consider the cost involved in the project? How do you strike a balance between the cost of stuff and the work in the studio?

JM: I make representational paintings, or at least, painting that looks like things. However my work has at its heart a relatively theoretical and conceptual relationship with both the object/subject and the process of painting. I am always aware of the costs of making my work; paint, canvas, brushes, etc. are not cheap and studio rent does place demands on my budget. Still, I have never not made a work out of concern for the cost.

Though I have been pursuing a career as an artist for longer, there was a moment, about twelve years ago when I committed to the medium in earnest. I resolved to buy what I needed when I needed it—even if other sacrifices had to be made.

I think that every artist wonders if they “have what it takes” to pursue a career in the arts. As there is no real measuring stick – visual art is a very subjective matter – it is difficult to gauge the relative merits of one’s own work. Early on in an art career the work and the artist have not yet been tested – so a sort of leap of faith is necessary to propel oneself through the beginning stages of that career.

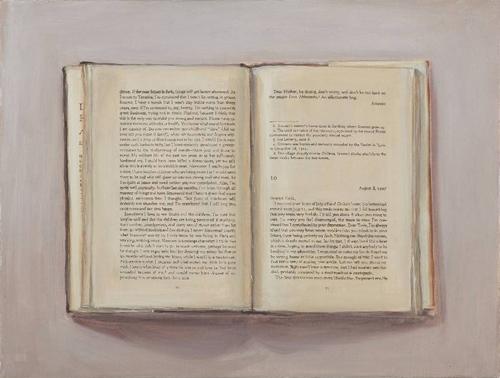

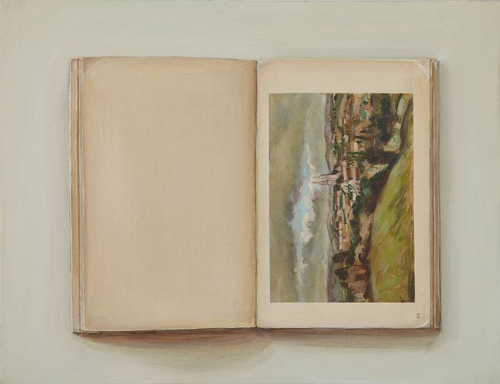

Jen Mazza. "Dear Tania (Gramsci, pages 90-91)," 2011. Oil on canvas. 13 x 17 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

BC: How do you manage your money, and how do you earn income? I want to know how economics, and money-management, affects your decisions inside and outside the studio.

JM: I rely on my teaching to cover my basic living and art-making expenses…well teaching and credit cards. When I sell work I use the income to pay debt and cover other expenses. I have not been able to save anything so far in my career. The main question is: how much time do I have to take outside of the studio in order to work in the studio?

I should also say that teaching—and other time out of the studio—does feed my work as an artist, and so on the whole I do not think that I am making major compromises. That being said, I generally spend what I make. Committing to this lean time to maximize my time in the studio seems crucial to making progress in my career.

BC: If you seek monetary compensation as an artist, do you see it as a possible compromise to the type of work you create, and your integrity as an artist?

JM: As paintings are objects, and sellable as such, compromising the type of work I create is less of an issue for me – as opposed to folks who work in installation, performance or other ephemeral or less sale-able media. I find it difficult to make paintings outside of the direction my work is taking at any given moment – they simply don’t turn out – so, for better or worse, I don’t make work to please the market. I am of course delighted when the market is pleased on my terms and work sells. I love the idea of my paintings engaging the world at large.

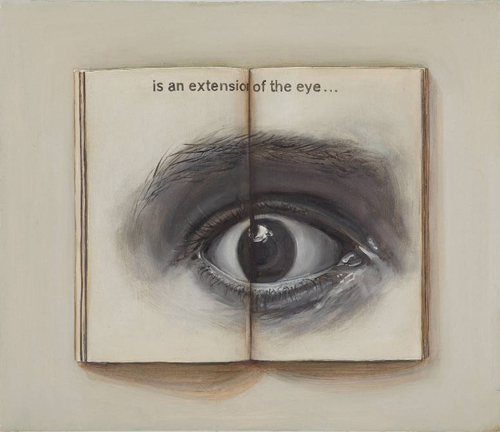

Jen Mazza. "is an extension of the eye..," 2012. Oil on canvas. 10 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

BC: Do you work to support your art, or does your art support you?

JM: I do basically work to support my art, but as I have mentioned teaching feeds my practice. I like working with students and I enjoy the exchange with my fellow teachers at the colleges where I am an adjunct professor.

BC: As an artist, how do you monetize your time, and how do you assign a monetary value to your studio practice?

JM: I don’t really—I’m quite neurotic as it is, if I worried about this I’d never make anything! I can’t help being slightly romantic and thinking of the studio as a “pure” space. Its value to me is beyond money or economic value. That said, I do realize that I have to cover the costs of renting the space and of my materials. I am also aware that having a studio and time to devote to my work as an artist is a remarkable privilege; a privilege for which I remain grateful.

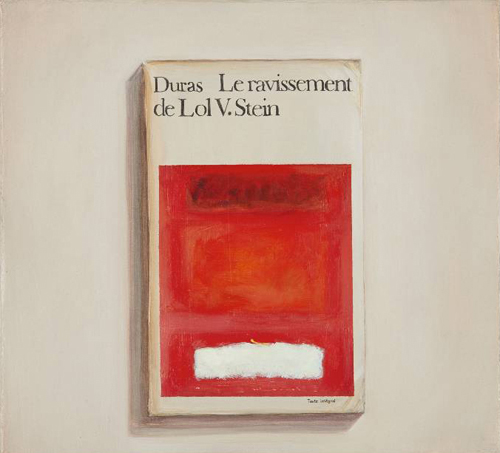

Jen Mazza. "The Ravishing of Lol Stein," 2012. Oil on canvas, 9 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

BC: What percentage of your income is derived from outside sources associated with your art? Teaching, lecturing, visiting artist?

JM: This varies from year to year. In a good year for painting sales, about half my income comes from sales of artwork. In a typical year art sales account for about 30% of my income. The rest of my income comes from teaching. I have no private income.

BC: The recent economic collapse laid waste to philanthropic giving, government subsidies, and slashed market prices for most artists. As an artist, there are no guarantees. How did you manage the current fiscal crisis, and how did it affect your work inside and outside the studio?

JM: At the time, the crisis in the market had a profound impact on my career. I was beginning to gain attention in the New York art world—I’d just taken a studio in the City — and it seemed as though I could be at a breakthrough point. Then… nothing. It was distressing. I was lucky—I think very lucky—in that I was able to keep on teaching and so did not face the dire economic problems that may other people suffered. Still, the budget was tight. I felt my career as an artist was “on hold.” In fact, or rather in retrospect, I now realize that work was at the beginning of a period of change.

The crisis in the market, strangely enough, coincided with a crisis in my studio practice. I spent six months making paintings and throwing away everything I made. And so, at the beginning of 2009, I began to feel that the things I had done before, the ways I had done them, no longer applied to what I wished to achieve, I even questioned what form achievement might take. So I began a process of gathering: reading, looking, imagining, without the ability or indeed the impulse for production. This fallow period went on for eight months before I noticed any change, and then I became suddenly compelled by very diverse images demanding to exist in paint. I have since struggled to keep up with the images as they appear to me.

Now in 2012 – I am on the eve of my first solo show in NY– I feel as if the last four years have been for me an amazingly productive period intellectually and artistically. I realize today that it can be as important for an artist to work outside of the public eye as it is to have an audience. I value the time I have had to interrogate my process as an artist and the solutions that have resulted from that time.

BC: Have you purchased the artwork of another artist? How did your financial investment in another artist’s artwork influence or inform your practice? (For example, as a result of buying another artist’s work, did you, in turn, begin to value your own work and practice more?)

JM: Yes I have. I didn’t really think about the financial value, it was just hard to find the little money I needed. So I suppose it reminded me that art is very much a luxury item for many people. If you can’t exchange with other artists (the way I have acquired most of the work I own) you do have to have a disposable income. I do like exchanging work with other artists; I feel that the value then is very real—I like and admire their work as I assume they do mine.

BC: You have exhibited your work in numerous nonprofit institutions over the years. According to the 2010 W.A.G.E. Survey (Working Artists for the Greater Economy), nearly 60% of artists that exhibited their work in cultural institutions did not receive any form of payment, compensation or reimbursement. It’s as if the art world expects artists to work for free. What other profession expects this of its workers, to give services away for free? Despite lack of remuneration, many artists agreed to the offer. Why?

JM: Of course, I do think that artists’ fees are a good thing. They should not be an afterthought, but an integral part of an organization’s fundraising strategy.

But that said, I think the key word is non-profit – these are generally organizations that raise and spend funds to support the community, both the artistic and the greater community. As an artist working with a non-profit, in many ways you are being paid “in kind.” Though you are correct that many non-profits do not provide an artist fee, I believe in NY state any organization receiving NYSCA funding is required to. Yet they do offer other services that are valuable – among these are installation costs and support, PR and marketing, increased visibility as an artist, press, and collector referrals – and non-profits don’t take 50% if you sell a work as a commercial space would.

I have found my relationships with non-profit organizations to be some of the most productive – since they are not dependent on sales they are the ones who can take chances showing emerging artists as well as less sale-able media like film or installation – and involve artists in an informed and engaged dialog that has a love of art and experimentation at its heart.

These organizations also tend to be run by, or to employ artists. In numerous cases directors and founders of non-profits may be working for free themselves – many donate their time and only begin to take a salary, if they do at all, when the organization is flourishing and they find they need all their time to devote to services (so that they must give up the other job that may have been supporting them all along). In other words – being a non-profit can be a lot like being an artist – you have a passion and you follow through with that passion at a cost to your person.

Why do artists do it? I think for the reasons above, and because it is true that as an artist, as in any business, there are investments that need to be made in order to succeed. Most businesses – art related or otherwise – have expenses relating to PR and marketing which they take in stride. An exhibition at a non-profit gallery is an opportunity to market the work at a relatively low cost to the artist, beyond the expense of actually creating the work – which is something I, as an artist, would do anyway – paid or not. Showing my work with non-profits has also led to commercial shows and sales. Oh, and so far as I can tell almost every profession now seems to require some free labor. What for profit or non-profit gallery is without its interns? Really what employer does not have interns these days? I don’t approve, but it seems to be a fact of life. And in the creative professions almost everyone has to work for free. Actors do showcases and their own productions; dancers too. Composers rarely get paid, musicians struggle, and as for novelists….and um… how about poets – probably one of the most difficult ways to make a living.

Pingback: 2nd post on Art:21 « HE SAID SHE SAID