In 2007, Jacob Reynolds, a former colleague, introduced me to Erin Riley-Lopez during an art opening at the Jersey City Museum. At the time, she served as the curator at The Bronx Museum of the Arts, where she organized the annual Artist in the Marketplace (AIM) program, a position she held until 2009. Currently, she’s the Curator of the Freedman Gallery at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania. Like many Americans affected by the recent economic downturn, Riley-Lopez had to weather an uncertain job market, which was fraught with financial instability and limited job prospects. Our interview discusses how she identified and then achieved her goal of becoming a curator at a national liberal arts college, where she has both creative freedom and newfound economic stability.

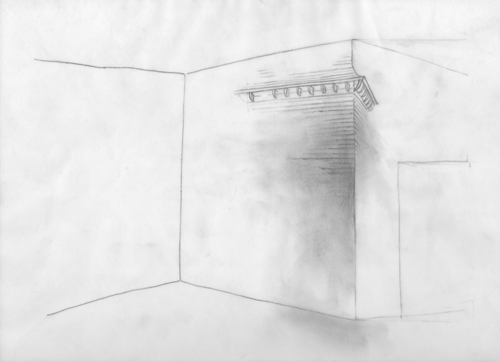

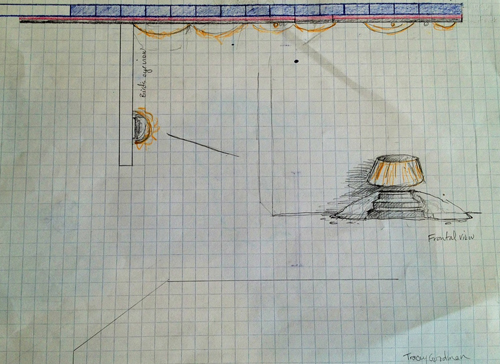

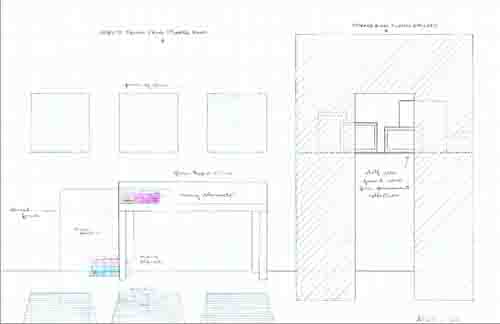

Erin’s inaugural show for the Freedman Gallery at Albright College, Interrogations, Interventions, and Modifications: Four Artists Employ Architectural Strategies, opens on Thursday, September 20, 2012. Using architecture as a point of departure, Sonya Blesofsky, Tracey Goodman, Amanda C. Mathis, and Alison Owen have created site-specific installations as a means to explore space—either gallery or residential.

BC: How do you manage your money, and how do you earn income? I want to know how economics, and money-management, affects your decisions as a curator.

ERL: I was an independent curator for a few years before I started working full-time again. The intermittent and staggered receipt of income while an independent curator made it difficult to manage money. I now have a stable, full-time position, which makes it a lot easier to know from where and when the money is coming.

BC: It’s as if the art world expects artists to work for free. What other profession expects this of its workers, to give services away for free? Despite lack of remuneration, many artists, curators, and other arts professionals agreed to the offer. Why?

ERL: I think there is an expectation that people in the arts will work for free or low pay particularly when they are just starting out. I think the more experience one has and the more one’s resume is built, that becomes less of an issue. I cannot speak for anyone else, but I was really excited to be involved in projects (even if I didn’t receive monetary compensation), when I was just starting out, because these projects helped me network, connect with people in the field, and provided me with invaluable experiences.

Across the board I think any industry, particularly those in creative fields, has its struggles in terms of monetary compensation. I am not aware of any standardized pay scales for museums or non-profits. I think each individual institution sets its own. We’ve been working at the Freedman Gallery to set up a standardized fee rate for freelance/independent workers as well as for artists’ speaking fees. I asked colleagues in the field to tell me what the going rate is for specific work, such as writing an essay.

BC: I want to know at what point in your career did you hit the resume building ceiling, and say to yourself: I am not curating this exhibition or working on this project because gallery “X” is not willing to pay me a decent fee.

ERL: I haven’t gotten to that point and don’t know if I ever will. Of course, it is nice to be fairly compensated for the work I do, but I don’t expect it. There’s always room for negotiation. As I mentioned, curating for me isn’t about the monetary compensation. It’s about contributing to the discourse surrounding contemporary art.

BC: As a curator, why do you feel it is necessary to establish a standardized fee rate for freelance/independent workers as well as artists? As a curator, do you feel the lack of a standardized feet rate for artists and workers compromises your effectiveness at organizing exhibitions and running a gallery?

ERL: Establishing a standardized fee rate for freelancers and artists is about making sure that they are properly compensated for the work they do whether it’s creating an artwork or project, an artist talk, or writing for a catalogue/brochure. The second part of your question relates to why this standardized fee rate needs to be implemented. It’s not just about compromising the effectiveness of running a gallery or museum; I just don’t think it’s fair to expect artists, writers, and other freelancers to work for little or no money.

BC: As a curator (and former independent curator), how do you monetize your time, and how do you assign a monetary value to your curatorial practice?

ERL: This is a somewhat difficult question to answer because institutions will often just offer a set amount for the work requested. Of course one can negotiate, but a lot of times non-profits just don’t have the money to give unless they have a grant or allocation of funds for a specific project. It also depends on the amount of work, time, and research expected.

BC: I still think it is an important question to ask. I know many professionals in the design field that have a day rate and hourly rate. If we (artists and curators) know what our time is worth maybe nonprofits will begin to allocate the necessary funds to not only realize projects, but pay us as well.

ERL: I don’t disagree with you on this point. I think the culture surrounding the pay that cultural producers receive should be standardized.

BC: Have you ever walked down the street in the middle of the day, and thought to yourself, I need to get a stable job, something conventional, with a consistent paycheck, benefits, paid sick days, and vacation time? What’s your bottom line?

ERL: Of course, especially when I was working independently! But I am currently in a great position with a consistent paycheck, benefits, paid sick days, and vacation time, so that’s really no longer an issue for me.

BC: Why do we become curators in the first place? Is it for the money? Is it for personal satisfaction? Is it for critical validation? Is it for a position in a blue-chip gallery or national museum? What is the reward?

ERL: I became a curator because I had been working in the commercial gallery world for a year right out of college and I decided at a certain point that I no longer wanted to think and talk about art in relation to its monetary value. It just wasn’t interesting to me to think about art in those terms and in galleries, the sale is always the bottom line. So I went to graduate school to become a curator because I wanted a balance between being creative and scholarly pursuits. I think at some point I did think that earning a masters degree would bring my pay scale up, but I was sadly mistaken when I realized that the non-profit sector, especially in the arts, is not about money.

That being said, I never went into the arts thinking I would earn lots of money, and I did know on some level that the pay scale isn’t as high as other industries. I curate because I love it, not because I want money. The reward for me is getting to work with living, contemporary artists and engaging in a constant dialogue not only with artists but with other arts professionals.

For me, it’s about putting something out into the world (an exhibition, a piece of writing, etc.) and hoping that it will make people think differently or approach art in a different way than perhaps they are used to. My curatorial practice has always been about both engaging and challenging audiences’ perceptions.

BC: You curate not for money, but for the love of working with artists, and other arts professionals. Labors of love do not pay the bills, or keep the debt collectors away. You are a seasoned professional, with major museum exhibition experience. Why don’t you want to earn money for doing what you love to do? Is the pursuit of money and earning an income somehow antithetical to being a good curator?

ERL: Let me be clear, it’s not that I don’t want to earn money for the work I do. Of course, I have to pay bills and want to live comfortably, but I also know the market, especially right now, and it’s about being mindful of this. To further clarify, some people choose a profession specifically to make tons of money. That wasn’t the main reason I chose my profession. I chose to be a museum curator so that I could be involved in the contemporary art world and add to the dialogue. Earning income is not antithetical to being a good curator, but for me earning tons of money is not my sole purpose in life. I just want to be fairly compensated for the work I do.

Amanda C. Mathis. "Foreclosure (131 Oley Street, Reading, PA)," 2012. Home interior: Paneling, wallpaper, drywall, paint, linoleum flooring, wood flooring, ceiling tiles, molding. Dimensions variable. C-print: Edition 1 of 3, 24 x 36 inches.

BC: The recent economic collapse laid waste to philanthropic giving, government subsidies, and slashed market prices for most artists. How did you manage the current fiscal crisis, and how did it affect your work and your curatorial practice?

ERL: When the market crashed, I realized that I couldn’t take anything for granted, especially my career. If anything, I think it made me work harder to seek the right position for me that would allow me both financial stability and freedom as a curator. Although it took me two years to find the right position, I finally did. It was tough to work independently, but I learned not to give up on what I wanted and I worked tirelessly to achieve it. I am happy to report that I found a job that has fulfilled all of my personal requirements for a curatorial position.

BC: How did the market crash, and your time as an independent curator, sharpen your vision, and help you to achieve your goals?

ERL: It gave me the time and space to really think about my professional goals and what I really want from a curatorial position. Also, it helped me realize where I really want to work and what institutions are the best fit for me.

BC: Have you purchased the artwork of any artists? How did your financial investment in that artist’s artwork influence or inform your curatorial practice?

ERL: I just recently purchased my first painting. Although it is an investment, I am not a collector and I don’t think about buying art specifically in those terms. Buying an artwork is about supporting and encouraging an artist’s practice and career, which stems from my past and current experience of working with younger and emerging artists.

BC: You just came back from Documenta and the Paris Triennale. How was it?

ERL: It was great! The trip to Kassel and Paris left me rejuvenated and ready to come back to work with a whole new set of ideas and challenges for curating. I loved being abroad in an international setting and meeting up with colleagues in the field. I had some great discussions and was really able to spend time with the two exhibitions. They gave me a lot to think about, everything from approach to display. Now I have to sit down and read through and synthesize all of the material I brought back from Europe.

Pingback: Curator Finds Perfect Job (and makes a decent living, too) « HE SAID SHE SAID

Pingback: Process of Curation. | AltSpace&TechArt

Pingback: Process Of Curation: Creative Marketplace | Rachael Short