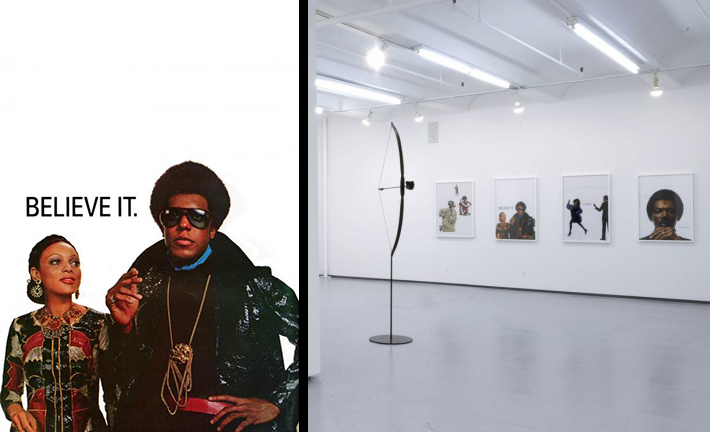

Hank Willis Thomas. “Believe It” from the “Fair Warning” series (left) and “What Goes Without Saying” (right). Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

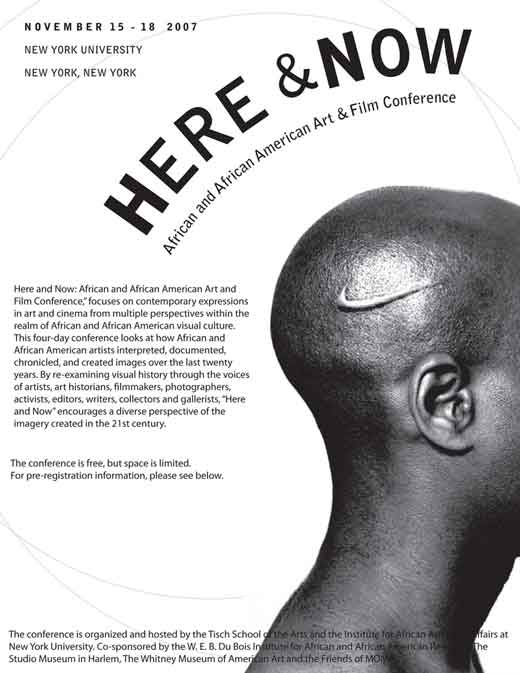

This entry is part interview, part review, and part reaction to works by artist Hank Willis Thomas. I first heard Hank speak at the Here and Now Conference at New York University in November 2007. The conference looked at how African and African American artists interpret, document, chronicle, and create images. Hank gained recognition with his Branded series (2006) for which he digitally added a scarred Nike logo on different parts of the body of a black model. One of the images was featured on the NYU conference poster.

Five years later I had a chance to speak with Hank about his work currently on view in Believe It at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) in Atlanta and in What Goes Without Saying at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City. Hank is also featured in the November 2012 edition of ARTnews, with artist Sanford Biggers in black and white on the cover.

Nettrice Gaskins: One of the things that interests me as a writer and a researcher is the ways that contemporary artists interact with the material forms and affects of technology. This includes the new notions of “hybridity” that you mention in ARTnews. Can you unpack this a little more?

Hank Willis Thomas: Everyone in America is a cultural hybrid. Black artists are often expected to have this authentic or mythical perspective. My experience of “hybridity” comes partly from the experience of being a minority in this country. Many of my contemporaries have had educations in environments that are not exclusively black and that influence our identities in ways that are often ignored. I talk about how we as African American men live within these different identities similar to W.E.B. Dubois’ notion of double consciousness. [I also refer to double consciousness in my post Kara Walker: The Art of War.]

Nettrice Gaskins: I’m also interested in your translation of existing cultural-historical artifacts, and how you re-purpose them to reveal the process of their agency. Can you talk more about that process? How do you start or organize this work?

Hank Willis Thomas: I grew up at the Schomburg Center where my mother (Deborah Willis) was once a curator, so I’ve been around and negotiated these artifacts for most of my life. Photographs capture moments and photographers turn these moments into documents and archive them. As a photographer I try to organize the world I’m seeing. I pay attention to the corner, the foreground and background of an image. I take it, look at it, throw ideas at it, listen to others’ feedback about it, sketch it, render it, and then over a long period of time, make it into a finished work.

Nettrice Gaskins: New media is my area of study at Georgia Tech, so I am always looking for how contemporary artists who work in or with traditional materials incorporate the new or now. How does new media figure into your production process?

Hank Willis Thomas: It depends. It depends. I’ve grown comfortable not limiting my work to my own talent or skills. Philip Perkis once said that form is nothing more than an extension of content. I look at what media I can employ to best articulate the content or concept I am trying to create. This forces me not to rely solely on photography to make a work.

Nettrice Gaskins: Can you talk a bit about how the work in the SCAD show links with work in the Shainman show?

Hank Willis Thomas: Some of the work at SCAD is in the new show. The images deal with framing and how forms of presentation influence how we read or understand a message or story. I am trying to figure out if there are ways to re-contextualize corporate-generated images to tell different stories of representation that aren’t solely in the service of selling a product like cigarettes in the Fair Warning Series.

Hank Willis Thomas. Installation view of “Fair Warning/Rebranded/Remember Me,” 2010. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid.

Hank began his SCAD lecture with the photo of a wooden Buddha he saw on display while visiting Vietnam. This Buddha was holding a MasterCard welcome sign that the artist feels is a metaphor for commodity culture and consumption, a major part of the “global culture dynamic.” He connected this memory to his practice of collecting, archiving (and re-purposing) cultural and historical artifacts. In my view, this is bricolage, or the process of figuring out how to make things work, not from standard rules or methods but from messing around with whatever materials are on hand. In this way, Hank Willis Thomas is an interpretive bricoleur. His artwork often consists of multiple interconnected images and representations.

“People ‘bricolage’ technologies, practices, materials, and the socio-political context together in a constant cycle of evaluation, mediation and translation – fitting new elements into the whole and adapting the whole to its new parts.” [Anna Dezeuze, Assemblage, Bricolage, and the Practice of Everyday Life, 2008]

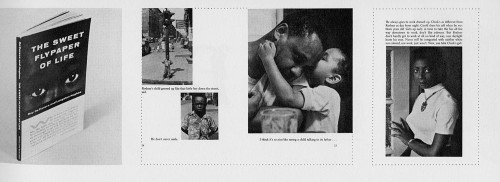

In addition to “commodity culture,” framing and seeing (from multiple perspectives) has played a big role in Hank’s work. He referred to the Sweet Flypaper of Life, a collaboration between photographer Roy DeCarava and writer Langston Hughes, as an example of an influential work. His mother, Deborah Willis, came across this book as a child and Hank says that this was the first time she had seen images that reflected black life as she experienced it in the 1950s. This led her to explore how the person holding the frame and taking the picture can effect the way we understand the world. Hank noted that African American photographers have been creating images of their world since the 1840s and these images reflected their/our understanding of history and everyday life–in contrast to the images that mainstream society was creating of African Americans at the time.

Hank shared his mother’s undergraduate thesis, which aimed to bring the work of African American photographers more to the center stage at a time when there were very few examples of their work in the history of photography. She proposed research that dealt with the inclusion of works by African American photographers, including Roy DeCarava, which become the source material for her first book, Black Photographers 1840-1940. Since then Hank has followed in his mother’s footsteps. He presented a collaborative piece called Sometimes I See Myself in You (2008) that explores how the relationship with his mother influenced his artistic practice.

I’ve previously heard Hank speak about (and have viewed work) from Branded (2006) and Unbranded (2010), so, in this post, I’ll write about his more recent work. I am intrigued by his exploration of different dichotomies, double entendres, and symbolic artifacts – i.e. as representations of social-political constructs, like “knowing what blackness is or isn’t.” For this work Hank references a quote from artist/writer Carl Hancock-Rux:

There is something called black in America and there is something called white America, and I know them when I see them, but I will forever be unable to explain the meaning of them….

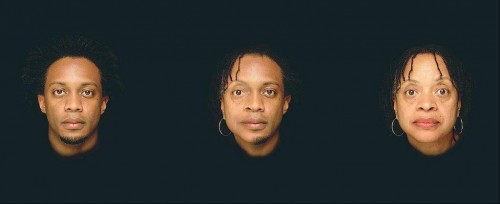

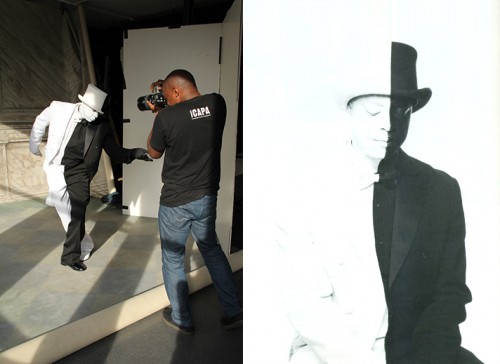

Hank recently staged a photo shoot with Sanford Biggers for the November 2012 edition of ARTnews. Rachel Wolf highlights a connection to ‘hybridity’ that I think is part of the emergence of postcolonial discourse and critiques of cultural imperialism. Wolf writes that, “Thomas wants to build his own take on the subject by combining… images, riffing on this idea of racial, cultural, and socioeconomic hybridity…” [Note: I revisit hybridity as polyculturalism on the Art21 blog.] In the ARTnews article Sanford says,

[T]his photograph and the character in it become more about duality and a more multifaceted being. It’s about the yin and yang, and pathology and moralism, and life and death. And superego. Those types of things. Which are things I’ve really been exploring in my recent work as well.

Hank Willis Thomas and Sanford Biggers. Photo shoot for ARTnews (2012). Photo (left) by Rebecca Robertson and (right) by the artist.

Hank’s interest in commodity culture and identity through multiple perspectives shows viewers how images/objects can diverge from common understandings of Black life in the Western tradition. Similarly, scholar Shigemi Inaga (2012) offers his treatise on art and globalization, i.e. as a “cross-reading” of Asian and African art that makes use of consumer goods. Inaga writes about the “metaphor of global resource circulation” that can be compared with Hank’s practice. Specifically, Inaga writes about the art of El Anatsui:

By recuperating the abandoned materials of commodity goods, accumulating the scattered pieces, and recycling them, El Anatsui weaves a collective memory of the world into his own texture, while letting the texture be woven back into the world [pg. 53].

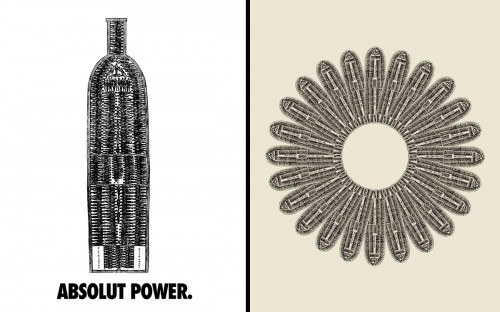

Sanford talked about being inspired by the weaving of vernacular (as collective memory) – i.e. American Southern vernacular, African vernacular and culture, mythology, history, and other artifacts from popular culture and Black life. Like other artists Hank Willis Thomas produces art that weaves the vernacular of his reality into his own texture, seeking solutions for our present time. El Anatsui, Sanford and Hank demonstrate symbolic bricolage by referencing their knowledge of culture, history, spirituality and their experiences as black men living and working within dominant society. For example, whereas Hank re-purposes the symbolic black and white image of black bodies on a slave ship and fashions it into the shape of a liquor bottle, Sanford uses the source image to create a flower motif.

Left: Hank Willis Thomas. “Absolut Power,” 2003. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery. Right: Sanford Biggers. “Lotus,” 2007. Courtesy the artist.

Call it chance or synchronicity that I was in Sanford’s Harlem studio talking to him about Lotus a month before viewing Absolut Power (2003) at SCAD. Hank talked about the Middle Passage, when slave traders kidnapped millions of people of diverse cultures, languages and identities, packed them tightly into ships, sent them halfway around the world and put them in the same category as a people. Even today, Africans and African Americans are largely seen as passive consumers. Inaga writes that Africa is more seriously touched and damaged by mass-consumption culture than successfully industrialized countries. Even in the United States some researchers note that the production of materials and technology in African American (and Latino) communities is still relatively rare.

Hank spoke about how comfortable we’ve become seeing certain kinds of images of Black people, especially in advertisements and sports. He said that mainstream audiences have grown used to seeing black male (athlete) bodies hanging from things like nets and some of them may have descended from people who were lynched during Jim Crow. The noose continues to be a symbol of domination used to threaten Black Americans, even during the 2012 Presidential election. Sports is a multi-billion dollar industry, fueled on the backs of the descendants of slaves, sometimes on the same fields where their ancestors picked cotton. Other artists like Kara Walker provide their own layers of meaning to these symbolic, cultural and historical artifacts. They take these images/objects beyond the American reality and, as Inaga writes, into the realm (and practice) of connecting seemingly disparate ideas and representations to create and expand their respective art forms.

The repetition of the connecting operation multiplies in proportion to the increase in the number of craftsmen involved. The gradual spreading in dimension of the (work) is… aimed at establishing solidarity among dispersed people [Shigemi Inaga, pg. 53].

African American creativity often centers on the vernacular. Throughout the trajectory of Hank Willis Thomas’ artistic practice he has woven the memory of Black America into his own images and assemblages. What I think is important about his art is that it reveals the multifaceted nature of the Black American experience, especially in consumer culture and in the practices of everyday life. During the SCAD lecture Hank talked about this process of engaging material artifacts as opposed to merely presenting black-informed expressive or aesthetic representations of the world. This work, as a type of bricolage, offers guideposts to new frontiers of production that rest in the liminal zones where multiple disciplines and realities collide. I believe that Hank’s work will inspire more underrepresented minorities to create, share, and distribute content rather than just consume it.

Hank Willis Thomas: What Goes Without Saying is at the Jack Shainman Gallery through December 8.

Hank Willis Thomas: Believe It is at the Savannah College of Art and Design through December 28.

Hank Willis Thomas in ARTnews is on news stands now.