Jeffrey Augustine Songco. “BOMH #1,” 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

The biggest news from the Miami art fairs this year was that the self-portrait is dunzo: first it was painting that was dead, then photography, now, it’s the self-portrait. And in the wake of a terribly tragic winter following Hurricane Sandy and the school shootings in Connecticut, it seems likely that American culture will shift from I, Me, and You, to Us and We. Perhaps we’ve arrived at the moment when we must put our personal beliefs aside and gather together as a collective whole to continue moving forward in a productive manner. But where does that leave the individual?

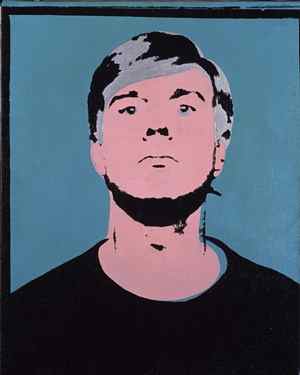

Andy Warhol. “Self-Portrait,” 1964. Image from tfaoi.com.

There was a time when all we wanted was the icon. Andy Warhol helped to usher in an era of American identity fueled by the self-portrait. His rapid serigraphic production questioned the notion that to have an identity required depth and humanity: it was just an object ready to be mass-produced. Celebrity would only last for 15 minutes, but boy was it fun while it lasted.

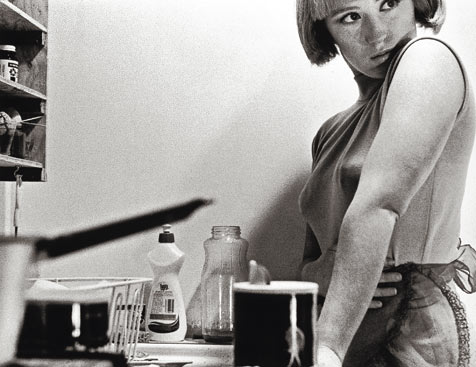

Cindy Sherman. “Untitled Film Still #3,” 1977. Image from guardian.co.uk.

As self-portraiture evolved, narrative was introduced. An individual’s identity shifted from mass-production to over-production – a layering of ideas on top of something already superficial. Cindy Sherman’s photographs revealed the fictionalization of the real through depictions of clichéd cinematic characters. As evidenced from this year’s touring retrospective, Sherman’s grand spectrum of characters leaves little room for any single individual to remain safe from cliché.

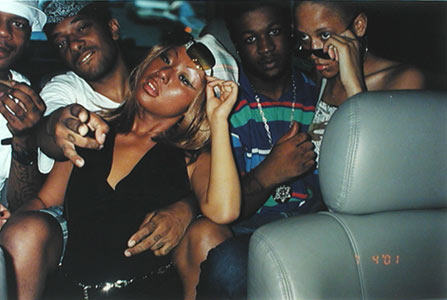

Nikki S. Lee. “The Hip Hop Project (1),” 2001. Image from skyemo.wordpress.com.

The cliché of individual identity soon left the private realm of the artist’s studio and entered the public domain. Nikki S. Lee appropriated and performed various identities within the sub-cultures and other groups within which those types existed. A kind of camouflage was suggested, but perhaps this signaled the nearing of the end of self-portraiture. Was there anything left to depict?

Matthew Barney. “Cremaster 3,” 2002 (detail). Image from mfk-juxtapositions.blogspot.com.

Actually, there was something left to depict: the production of the self as hero. Matthew Barney split notions of personal identity into expansive–and expensive–works of art in every possible media. The literal gooeyness evinced in his lavish works begged the question: was the self-portrait simultaneously ascending into fantasy, and descending into the very core of the human body?

James Franco. “Dicknose in Paris,” 2008. Image from tribecacitizen.com.

As if American culture had written this cyclical narrative itself, the last prominent artist to deal with self-portraiture during its time of prominence is James Franco, a man whose identity as a celebrity movie star goes to his core (for the general public, at least). Half a century after Andy Warhol created what were essentially anthropological studies of celebrity culture, Franco confesses and creates work about his real identity as an actor – an identity based on creating and depicting fictional ones.

Jeffrey Augustine Songco. “Hosanna,” 2012 (detail). Courtesy the artist.

Where does that leave self-portraiture now? The fact is, self-portraits will always be around, just like painting and photography will always be around, but its apparent “end” allows for the circle of life to begin again. Artists will continue to question the role that self-portraiture plays in their art, whether through the depiction of the artist’s own face, the materials one uses, or the personal or conceptual sites that inform a body of work. Whether or not the collective art world can stand to see yet another self-portrait of an artist is up to us to decide–and I have a feeling we’ll give it another whirl. The next seminal self-portrait artist just needs to figure out how to get us spinning again.