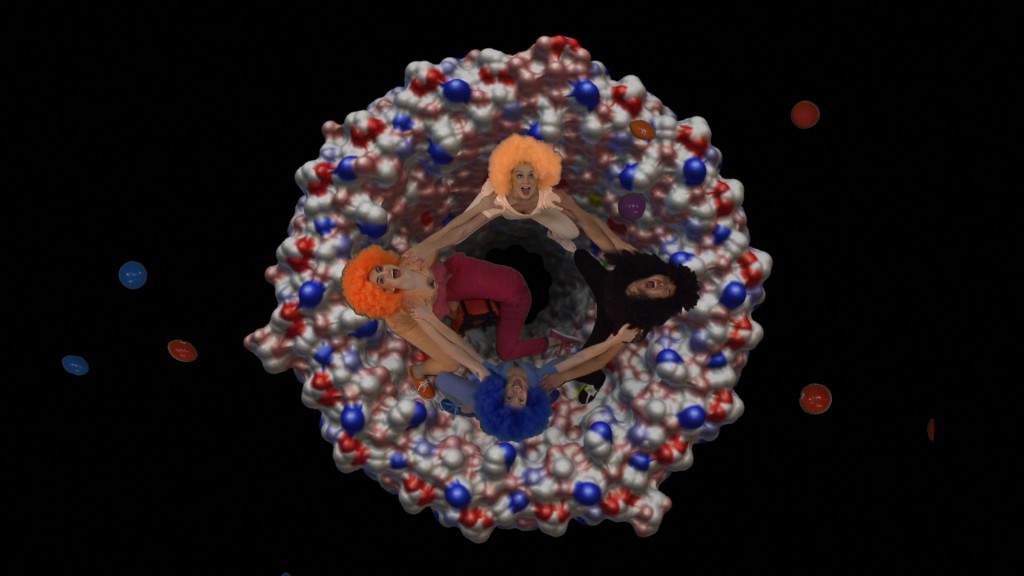

University of Michigan (clockwise, from top) dancers Riley O’Donnell, Kula Batangan, Lauren Morris, Penelope Koulos, and Ashley Manci (center).

Click. Click. Click. Click.

Red spike heels punctuate the floor in unison as four “harpies” in vibrant shades of pink, yellow, blue and orange encircle the intended victim. Their sharp steps keep pace with driving music that sets a tone for the devouring that is about to begin

A kaleidoscope of colors, abstract images, and geometric patterns projected from on high define the circular boundary of this choreographed conflict. The music becomes turbulent, dissonant as digestion begins.

Like most artistic works, this story has the typical elements of plot, character, conflict, theme and setting. The characters portrayed by University of Michigan dancers are the elements of a cell and the setting is the human body. The plot involves a process called autophagy, and the theme addresses this complex function our bodies go through 365 days a year, as each cell seeks to renew itself. Conflict comes when the process does not work as expected.

The five choreographed scenes represent a collaborative effort among a cell biologist, composer, choreographer and scientific illustrator, who seek to translate a complex cellular process that increasingly has captured the attention of the scientific community over the last decade.

“Almost every month there’s a new connection being discovered between autophagy and some aspect of human health and disease,” said Dan Klionsky, Alexander G. Ruthven Professor of Life Sciences, in the U-M Life Sciences Institute. “Defects in autophagy can contribute to cancer, some types of neurodegeneration, diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, various muscle diseases—you name it.”

Autophagy means self-eating, a process in which the cell destroys and disposes of that which no longer is needed while recycling essential parts worth keeping.

For years, Klionsky has been on a mission to translate science for lay audiences and students, to help them better understand intricate biological processes. He started with medical illustration, contacting David Goodsell from The Scripps Research Institute, who turned him down at first, saying there wasn’t enough evidence to do a realistic illustration.

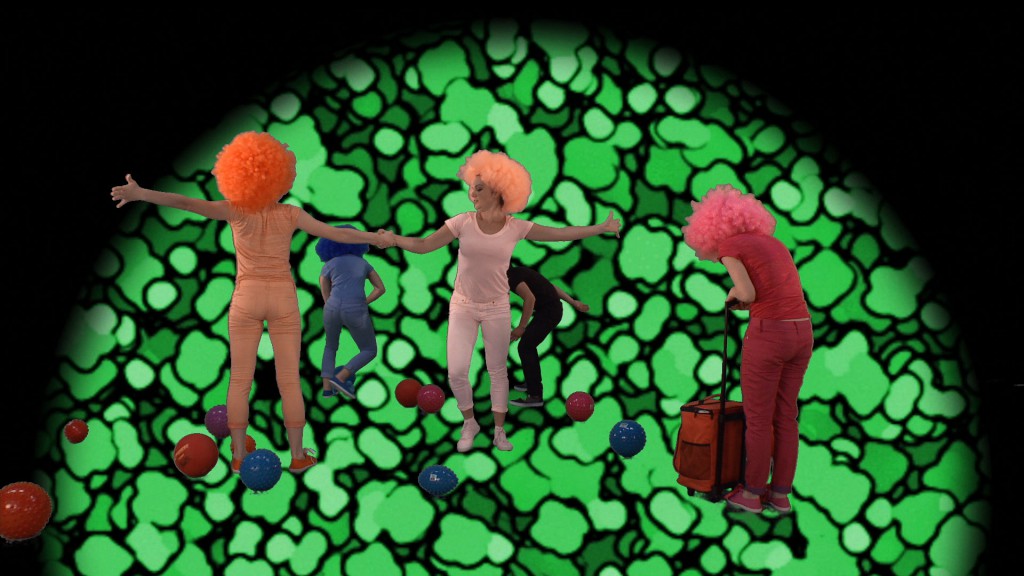

University of Michigan dancers rehearse the performance.

Fast forward to the pair’s fourth collaboration, and Goodsell’s drawings that form a cell-shaped backdrop for the dancers represent an interpretation of things seen through the most powerful microscopes and the best information available to fill in the blanks.

“We take the data and cast it with an interpretive, visual feel of what it would look like if we could see it,” Goodsell said.

Eventually, adding illustration was not enough for Klionsky, who, along with others, experimented with simple-toned music based on DNA and then protein sequences. This led him to ponder what more sophisticated compositions could do to increase understanding.

He connected with U-M alumna Wendy Wan-Ki Lee, a faculty member at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, to talk about setting autophagy to music.

“I thought about the entire process; how I can put that to music in more emotional terms,” Lee said.

She started with what she considered the climax, the digestion part, using clusters of notes her collaborators referred to as “rhythmic turbulence.” Then she focused on the point at which the cell experiences nutritional scarcity, right before it begins to eat itself. “I thought how would a person respond to this, and I came up with a section of unresolved harmonies,” Lee said.

Membrane formation was depicted with notes in both hands that increased in speed and frequency, and eventually created a semi-circular effect to signal complete engulfment. Fusion became unison octaves, moving in the same direction.

Lee’s first interpretation, a solo piano piece called “Macromusophagy,” was a centerpiece for the larger collaboration, the logical next step.

“We’ve done paintings. We’ve done the music. I want to do dance,” Klionsky said.

This is where Peter Sparling, Thurnau Professor of Dance at U-M, comes in. Sparling, who is no stranger to collaborations with scientists, is a screendance artist who combines video imagery with live performance, choreographing and editing together complex productions.

A scene from the collaborative performance.

“So, call me the ring master,” he said. “I choreograph the movement for the dancers. I choose the images—the visuals. I choose the music. I decide the scenario. I put the visual images and the music and the dance together so that it all fits.”

But don’t expect a precise translation of the science from Sparling.

“I didn’t want to create dances that were literal illustrations of something. I wanted to make a metaphor,” he said. “I wanted to interface Dave’s drawings with images of human figures: emulating, imitating, mimicking and embodying these processes in a simplistic way.”

Enter a male outsider in black rocker shag, who finds himself surrounded by four stiletto-heeled club denizens. To a crescendo of dramatic chords struck on the piano, the women distract then exhaust him in their frenzied pursuit. He lies spent, as they pick his pockets of precious cargo: red balloons that they inflate then let fly into the darkening air.

Laurel Thomas Gnagey is senior public relations strategist at the University of Michigan.