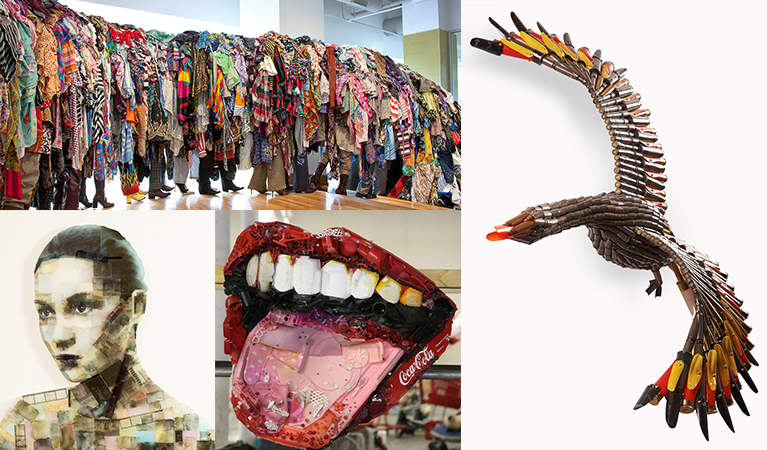

Clockwise from top left: Guerra de la Paz’s Follow the Leader; Federico Uribe’s Red Goose; Tom Deininger’s Lips; Nick Gentry’s Switch.

Every day, each of us is responsible for generating almost five pounds of trash. That’s more than one thousand six hundred pounds per person every year. With all that junk, it’s no wonder why some artists create straight from the garbage can, using discarded items to construct beautiful, sustainable works of art. For this issue, I asked four such artists for their thoughts on the process and motivation driving this fundamental form of renewal.

Tom Deininger. Timelapse of Self Portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

1. Tom Deininger

Tom Deininger uses what others throw away to build sculptural collages out of old toys, plastic cutlery, cigarettes, and colored pieces of plastic that have long been separated from the game or device they belonged to. He has made mandalas out of bottle caps and built a rabbit out of cigarette filters. He even recreated Monet’s painting, The Japanese Footbridge, from old Kermit the Frog and SpongeBob SquarePants toys. In portraits, his plastic pointillism reminds viewers that we’re made up of what we’ve inherited, and his more abstract, large-scale works force us to confront how wasteful our consumerist society has become.

Lindsey Davis: Why do you want to give discarded materials new life in your sculptures?

Tom Deininger: I try to be very democratic with my appreciation of esthetics. Objects interest me—high and low, clean or dirty. Detritus isn’t inherently ugly or beautiful; it can be both. Because our value conditioning or gut associations essentially deem worthless things unappealing, trash just “appears” unattractive to most people.

Interestingly, that’s where all the potential for it as a medium of expression lives: the unexamined or overlooked often speaks profound truths about us as a culture and as a species. It says that we are amazing makers and aggressive consumers; both have unintended consequences. I also am disturbingly frugal and try to find a way to love or at least appreciate the most unlovable and most underappreciated things. I also like underdogs. To sum up, I hold onto two quotes: Marshall McLuhan said, “The medium is the message,” and George Oppen wrote in a poem, “There are things / We live among and to see them / Is to know ourselves.”

Tom Deininger. Lips. Courtesy of the artist.

2. Federico Uribe

Colombian artist Federico Uribe has created entire immersive installations from collaged materials, building animals from fabric and wires, plants from shovels, and stars from silver keys. Uribe has adapted pencils as a medium again and again; in some works, he draws parts of a scene to contrast against the elements made of those very same colored pencils, and often he’ll glue pencils on top of others to create a thick, three-dimensional, crosshatching effect. All of his work carries a sense of whimsy, sometimes facetious and irreverent, other times cheerful and pure. His Torsos series includes Cybersex—a headless, limbless, female mannequin covered in tempting computer keys—and Screwed, a male torso made of shimmering, protruding, gold screwheads.

Federico Uribe. Red Goose. Courtesy of the artist.

LD: What’s your favorite part of the artistic process? Are you ever surprised by your own creations?

Federico Uribe: The best moment is when I finish a piece, especially when it was hard to do—when I’ve achieved making an object that’s as good as I had seen it in my head.

Yes, I am surprised most of the time; it always seems as if I could not have done it.

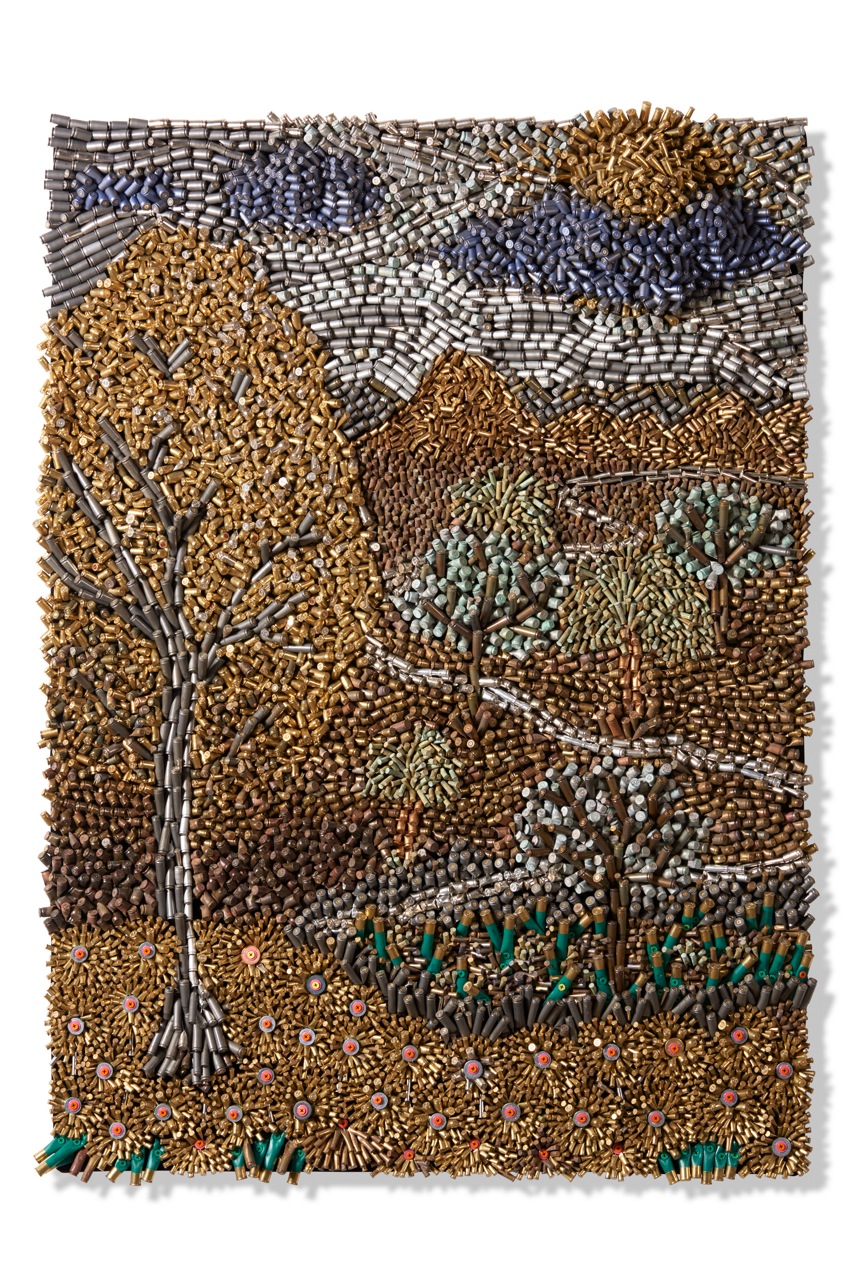

Federico Uribe. We are all Innocent. Courtesy of the artist.

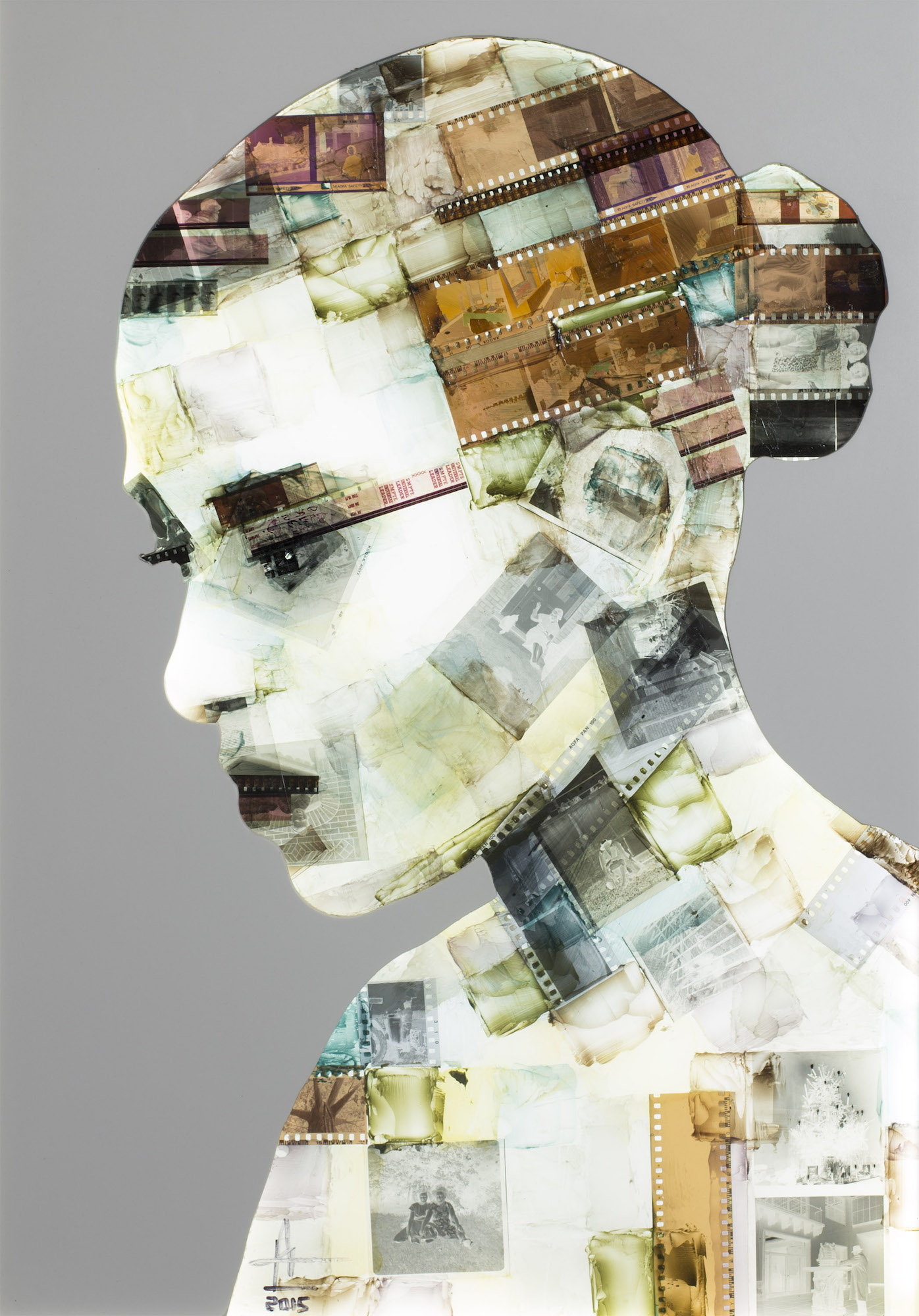

3. Nick Gentry

Nick Gentry’s work is specific both in the media he repurposes and in the images he creates. Gentry uses film negatives, x-rays, microfilm, and floppy discs to construct haunting portraits, usually seen from the shoulders up. He paints eyes, noses, mouths, and ears with acrylic and oil on these collaged compositions, and sets each piece within a light box that illuminates the film strips that make up each face. By recycling these outdated forms of physical data, Gentry casts each face as an assemblage of memories and information that can only be seen if a viewer is willing to look closely. In the case of the floppy discs, that information is completely out of reach, simultaneously symbolizing lost modes of communication and the hidden aspects of our innermost selves.

Nick Gentry. Zone, 2015. Film negatives and acrylic paint in LED lightbox, 59cm x 42cm. Courtesy of the artist.

LD: Is there any connection between the images you create and the images on the floppy disks or in the film negatives? Or are you more driven by the simple task of creating something new and beautiful out of discarded materials?

Nick Gentry: I like to make connections not only throughout each portrait but also beyond the portrait, into the lives and histories of the viewers. The whole process is completely open and inclusive. The art cannot exist without the contributor or the viewer. However, a lot of these connections are ambiguous and left open to individual interpretation. I do find a certain beauty and charm in old, discarded materials. I feel lucky to have such a choice in that area!

Nick Gentry. Switch, 2015. Film negatives and acrylic paint in LED lightbox. Courtesy of the artist.

4. Guerra de la Paz

The Cuban-born artist collective Guerra de la Paz also creates using a specific discarded object: clothes. Inherently personal, each item of clothing is inseparably linked to the body that once wore it, bringing hundreds, sometimes thousands of lost identities and histories to each work. Their sculptures of shirts and sweaters investigate the psychosocial implications of humanity’s collective impact on the environment, while each singular piece of fabric invokes the individual, conveying the consequences of one person’s material contribution.

Guerra de la Paz. A Stitch in Time: Ghost Variations, 2000 – 2016. Installation image: 2016. 108 white deconstructed garments, 108 white wire hangers on 9 foot metal pole. Courtesy of the artists and Chloe GIll-Holster Projects.

LD: What is it about art made from clothes that you find most compelling?

Guerra de la Paz: It is a material that serves as a testament to humanity, no matter how it’s used. Everyone can personally relate to it. Though for us, it is more about the fact that the clothes have been worn and discarded before they reach us.

Used clothing is charged with layers of history. Each garment comes with a story from a previous life and provides an existential quality to the work from the start.

The use of clothing in our practice is a product of the classic case of being in the right place at the right time. We were once surrounded by export businesses that would cast-off thousands upon thousands of rejected items on a regular basis. They would allow us to rummage though and collect as much as we desired, providing us with a sea of salvaged materials that have guided our concepts.

Guerra de la Paz. Follow the Leader, 2009. Found patterned garments, wood, footwear and hardware, approx. 75 feet long by 7 feet tall. Courtesy of the artists and Chloe GIll-Holster Projects.