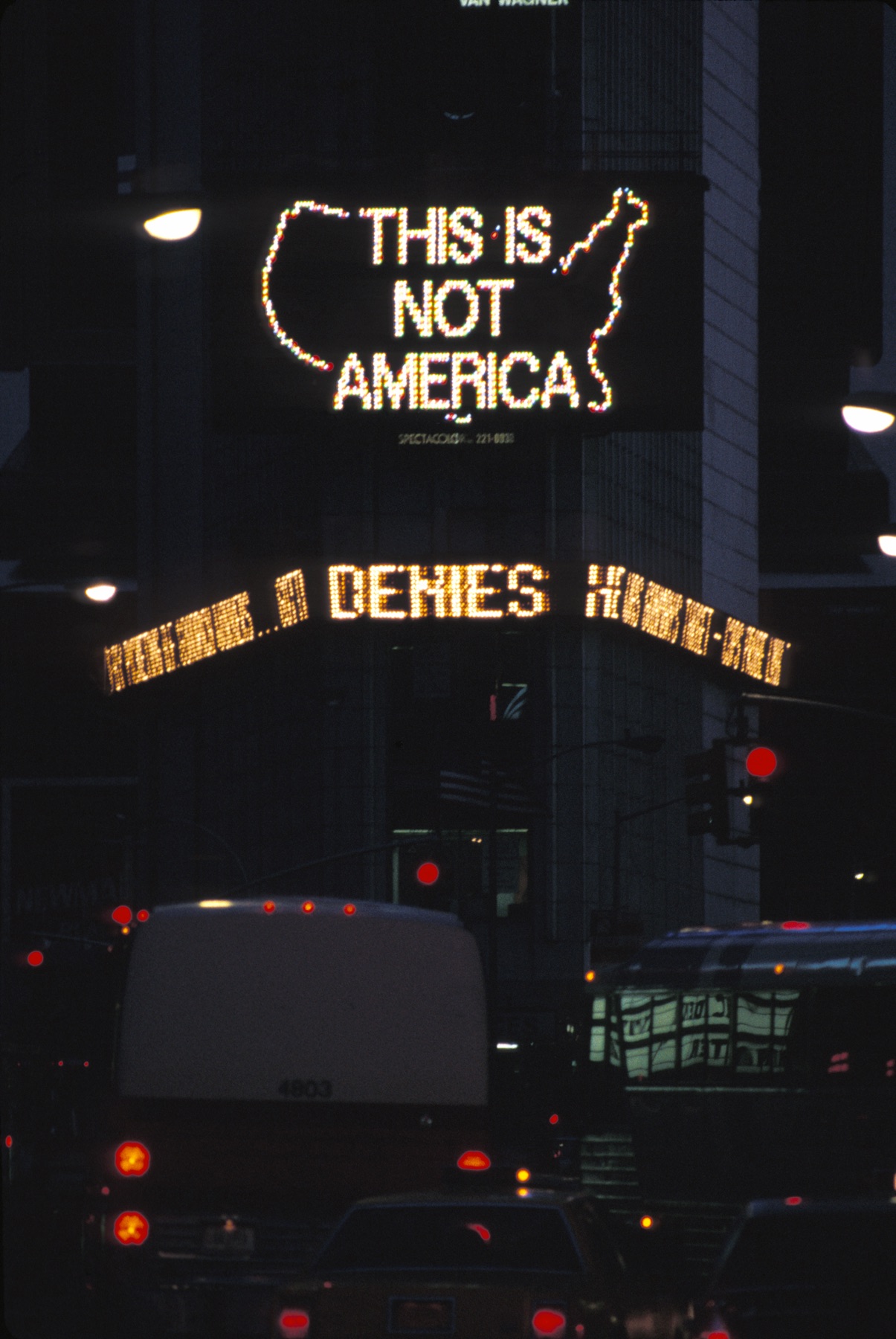

Alfredo Jaar. A Logo for America, 1987-2014. Public intervention. Digital animation commissioned by The Public Art Fund for Spectacolor sign, Times Square, New York, April 1987. Courtesy of the artist and Times Square Alliance, New York.

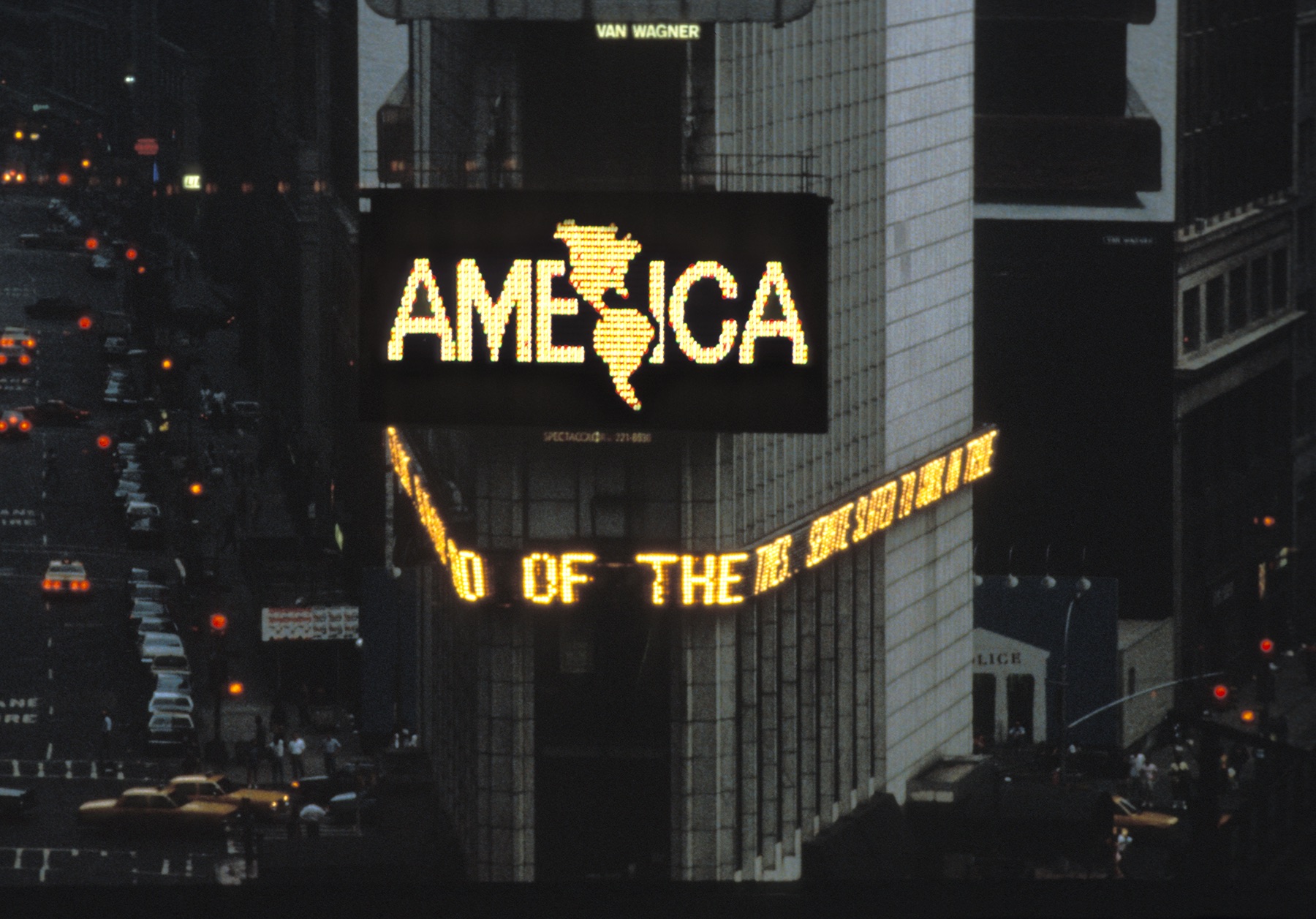

For over a month in 1987, one of the electronic billboards in Times Square displayed a forty-five second sequence that interrupted the commercials. Every six minutes, the advertisements would be replaced by a artist’s narrative: an outline of the United States surrounded by the text “THIS IS NOT AMERICA,” followed by the flag of the United States that dissolved into a second text that read “THIS IS NOT THE AMERICAN’S FLAG.” The word “AMERICA” emerged next, and would dominate the entire screen as the central letter “R” transformed into the continents of North and South America.

The realization that the word “America” had been incorrectly used to refer to a single country began to spread. Almost thirty years later, what was presented as a linguistic correction critiquing the authoritative attitude of the United States towards South America, is even more relevant. The work has been presented in Times Square twice, in Mexico, and this summer it’s coming to London’s Piccadilly Circus. With the creation of new borders, and the possibility of new divisions on the agenda in both the United States and Europe, it’s not surprising that A Logo for America is often described as the twentieth century’s most significant piece of political art.

Maria Pia Masella: How has A Logo for America changed since its making in 1987?

Alfredo Jaar: That work had been sleeping since ‘87, when Pablo Lèon de la Barra, the curator of Under the Same Sun: Art from Latin America Today, came to see me few years ago and said, “Why don’t we show it again in Times Square?” I was delighted with the idea, but Times Square has radically changed in the last 30 years. When I did the piece, we had one screen and there were maybe five screens in total in the square. Nowadays there are 135 screens and we were able to do it on sixty-five screens simultaneously. It was extraordinary for me to see it in that context.

Then, Pablo kept going and said, “Why don’t we show it in Mexico?” And I thought, “It does not make any sense; the work is in English and you are going to show it in English to Mexicans?” But he said, “No! People understand and it makes a lot of sense with Trump and the borders!” So I accepted, and now the piece is in London. It is almost becoming Pablo’s work [laughing]. What I am saying is that I want to give him credit for this, because I never thought the work could have such an impact around the world and I am thrilled with that. I never expected that it could have such long term relevance.

It was designed at the time as a work on language. I wanted to suggest that language is always a reflection of the geopolitical reality and—at the time—the reality was one of domination of the United States over the entire continent. This is why people say “God bless America,” or “Welcome to America” to refer only to the United States and not to the entire continent. I thought, this language problem will always exist until the geopolitical situation changes. If we become equal partners in the continent it might change, but of course it has not changed.

Regarding the meaning of the work, it has become richer. It has expanded into other fields. For example, in the United States, the immigration issue is very important. The Obama administration has been very disappointing to the Latin American community. Obama has extradited more than two million immigrants in the last four years. He has extradited more immigrants in four years than Bush did in eight years. The Economist published a story on this: “Barack Obama, deporter-in-chief.” So when the piece was shown again in Times Square in 2014, it was not so much about the original meaning of the language—it was more about the meaning of America. It asked the question: “What does it mean to be American today?”

Alfredo Jaar. A Logo for America, 1987-2014. Public intervention. Digital animation commissioned by The Public Art Fund for Spectacolor sign, Times Square, New York, April 1987. Courtesy of the artist and Times Square Alliance, New York.

MpM: What is the meaning of this work in London, now in 2016?

AJ: The United States, as a nation, is so powerful that even when people from London go there, they say “I am going to America,” and that’s the same for most Europeans. Showing A Logo for America in London makes sense because I am trying to claim the term “America” for the entire continent. If we could make this correction in Europe, that would be fabulous.

MpM: About the Economist and your relationship with published information, would you agree that the media seems to work as both a medium and as a source of inspiration for you?

AJ: Absolutely. How do we inform ourselves about the world? We have our parents, we have education, and then we have the media. The media is an invisible landscape that is part of our daily life; people are not aware of how it bombards us with information of all kinds through the internet, through television, through magazines, through newspapers, billboards, and social platforms. Every fragment of information the media puts out contains an ideological conception of the world. Its messages are not innocent; they try to sell us a specific picture of the world, and most of the time a very conservative one. So that’s why I am interested in the media and I have created a series of works around the politics of the image. I am interested in analyzing certain media constructions to try and reveal their structures and their meaning to the audience.

Alfredo Jaar. The Sound of Silence, 2006. Wood structure, aluminum, fluorescent tubes, LED lights, flash lights, tripods, video projection (8:00 loop). Software design by Ravi Rajan. Installation views at École des Beaux Arts, Paris, 2011. Photo by Charles Duprat. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Galería Oliva Arauna, kamel mennour, Galerie Lelong, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

MpM: I am thinking about The Sound of Silence (2006), May 1, 2011 (2011), both built around a single, well-known image which triggers reflections on hidden dynamics of power. Language is carefully used to reveal the latent meanings of images.

Similarly, but with a reversed logic, in projects such as Real Pictures (1995) and The Lament of the Images (2002), words are used to describe images that are denied to the audience. How important is narrative in your work?

AJ: Each project is new, and is specific to the place and to the context. Sometimes I tell stories, sometimes I comment on stories, sometimes I invent stories. I need words to build up stories, films, and sequences, and to assist the audience in understanding my works. In the case of The Sound of Silence, there was a short eight minute film with only text. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken by Kevin Carter in 1993 is seen only in a fraction of a second after a moment of blindness is caused by a flash. For this work, I wanted to create a theatre built around a single image, a huge structure of 228 cubic meters which already suggests the importance of images and how they affect the way we think and understand the world.

The Sound of Silence is the first of a trilogy of works. I just inaugurated the second one in Paris called Shadows and I am currently working on the third one. In Shadows, I am telling the story of an extraordinary image alongside other images without using a single word. So I have changed the strategy. When I went to Rwanda to witness the genocide, I took thousands of pictures but I was not able to use them because I felt that the world had ignored that genocide. It was a criminal indifference and I felt that my images would not make a difference, so I invented different strategies of representation in order to tell the story of the three thousand images I took. I enjoy using different strategies.

Alfredo Jaar. May 1, 2011, 2011. Two LCD monitors and two framed prints. Original White House photograph by Pete Souza. Photo by Frazer Spowart. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, kamel mennour, Galerie Thomas Schulte.

MpM: Do you trust words more than images?

AJ: I use words because sometimes I distrust images, but I also need words to assist the image. Words are part of the mise en scène I create to direct your gaze towards certain aspects of the image that I am interested in exploring and eventually present. I am a great lover of poetry. I read haiku poetry a lot. These are very short poems with three lines and fifteen words, and what I like about haikus is their economy of means—their capacity to say so much with so little. That is what I try to do as an artist. Every project of mine, I am always thinking about the haiku model.

MpM: You often say “I am an architect who makes art.” In my view, your use of space and light confirm that background. Are there other aspects of your work that you associate with the way architecture works?

AJ: Yes, I use light and space to engage my audience. My methodology, my way of thinking, my way of approaching an issue is the way of an architect. I also have a studio with very talented people who help me to complete my works. I never studied art, so I am still finding out what art is and it is a marvelous journey because I am learning all the time.

Alfredo Jaar. Shadows, 2014. Mixed media installation. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, kamel mennour. Original photographs by Koen Wessing (1942-2011) in Estelí, Nicaragua, September 1978. © Koen Wessing / Nederlands Fotomuseum.

MpM: What about the research you undertake prior the realization of your works?

AJ: Research is part of every project and can last between one and six years. When I reach a critical amount of information where I feel that I have attained a level of responsible knowledge—at that moment I dare to venture into a project.

MpM: Do you think that your audience requires time to fully engage with your works?

AJ: Yes, and in that sense time is a source of frustration. Studies have shown that the average time that the audience spends in front of an artwork in a museum or a gallery, is three seconds. The artist works for years in his studio spending thousands of hours thinking about their work, creating it, changing it, modifying it, sitting in front of it, looking at it again and again, and when the work is finally put out, people just walk in front of it.

This is why I create mise en scènes around my works which almost suggest “Please stay! Give me a minute, two minutes. I want to tell you something!” Most of the time, I succeed and people stay because the construction is too complex to walk by. My architecture invites people to stop—”Look there is a mirror there! What’s going on over here!” You have to invent things in such a way that the audience gets physically engaged, and with that bodily experience there is a hope that the work can also engage people mentally. To communicate with another human being in the artistic language is very difficult and there are many barriers. Which is why the model of the haiku is very useful to me. And this is the reason why I admire Ungaretti. He wrote the shortest poem in the history of literature and I have made a neon in homage to that poem, M’illumino d’Immenso. An artist from Chile, who lives in New York, pays an homage to an Italian poet—it is ridiculous. But I could not believe that no one had done that before! I cannot imagine two better words together, creating this explosion of meaning and joy. Just two words. That is what I want to do as an artist!