Installation view, Steven Shearer at The Brant Foundation. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

The Brant Foundation’s exhibition of Steven Shearer is essentially a mid-career survey. This in-depth plunge into Shearer’s world of long-hair miscreants spans twenty years of the artist’s production. Organized largely from Peter Brant’s collection, important additional loans and preparatory sketches were brought in to realize a show that foregrounds Shearer’s cumulative processes. Here, Steven Shearer exposes his Vancouver roots; a city that has distinguished itself through researched-based artists interested in notions of history, who actualize materially sophisticated works of art.

From the first picture, we are swept up in focused torrents of images. A Pollock-esque splatter of internet-culled snaps, capturing the expressive exploits of virile guitarists, covers the expansive white field that barely contains their collected mass. Guitars #5 (2002) could be used as a map for Shearer’s project, one dedicated to relishing artistic potential. Since this relatively early period, his method has found a historical foundation. There has consistently been a specific, potentially romantic, subject at the centre of his archiving. Like the lone guitarists slamming their metallic discord, this figure presents an alienated perspective; their combined mass revealing a cultural perspective, torn from the basements of rebellious youth.

Steven Shearer. Sleep II, 2015. Inkjet print on canvas, triptych. Overall: 112 1/2 x 272 inches. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

Steven Shearer. Sleep II (detail), 2015. Inkjet print on canvas, triptych. Overall: 112 1/2 x 272 inches. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

The exhibition at the Brant makes his addiction to archiving apparent. The second collection encountered is made up of 132 scraps of paper, each enshrined in its own frame and presented in a dense salon hang. Scrap #2 (2003) is a collection of adolescent curiosity and deviance. Here, layers begin to build on each other. Reproduced in laser print and dispersed amongst the rockstar fan shots, peculiar photos and teen doodles, surface reproductions of other image archive works, like Guitars #5, the artist has made of owls, metal heads, garden sheds, etc. Scrap #2 emphasizes this material as evidence for the fecund potential of Shearer’s revolutionary idols.

The first large gallery is paneled in grey upholstery, and hung with portraits in ballpoint pen, crayon, and oil. These protagonists are seething with the cultural influences chronicled in the earlier archive projects. The sense that these sources accumulate was furthered by a vitrine, set in the far wall, which presents paintings and collages in conversation with sketches and drawings. Images are repeated and reworked, used as models to be drawn upon. Laser prints are enhanced with moody brush strokes, revealing photographic worlds behind the painting process. The amassing of these various miscreants realizes an additional depth to the project as you could see the references assembling within each portrait, the process resonating dedication to what is essentially a singular project.

Installation view, Steven Shearer at The Brant Foundation. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

I call Shearer’s project singular despite the exhibition spanning the scope of his production, which notably incorporates text, silk-screening and collage. Graphically, these other works feel quite different. But I maintain that they also are realized through his interest in amalgamating aspects of dissident youth culture into mythic figures. The methods of Pop are stolen here—Warhol, maybe a little Johns—an expanded archive work of collapsed sleepers sprawled on canvas to the scale of a Rosenquist. He acquires these historic forms here for his hero.

I say mythic, instead of fantastic or imagined, because there is a feeling that meaning can be drawn from these composites. I call them composites, as that is what the new paintings have definitely become. Alongside the accumulation of references, Shearer catalogues and documents the evolution of his production, photographing the layers as he works; looking at reproductions of various gestures he’s developed to achieve particular effects. These also become references, models for working out the next evolution. Shearer’s studio is state of the art, and increasingly he can lift slices and insert parts of past images, even printing them directly on the canvas, to then build new complexities. This is felt more then realized in his newest works.

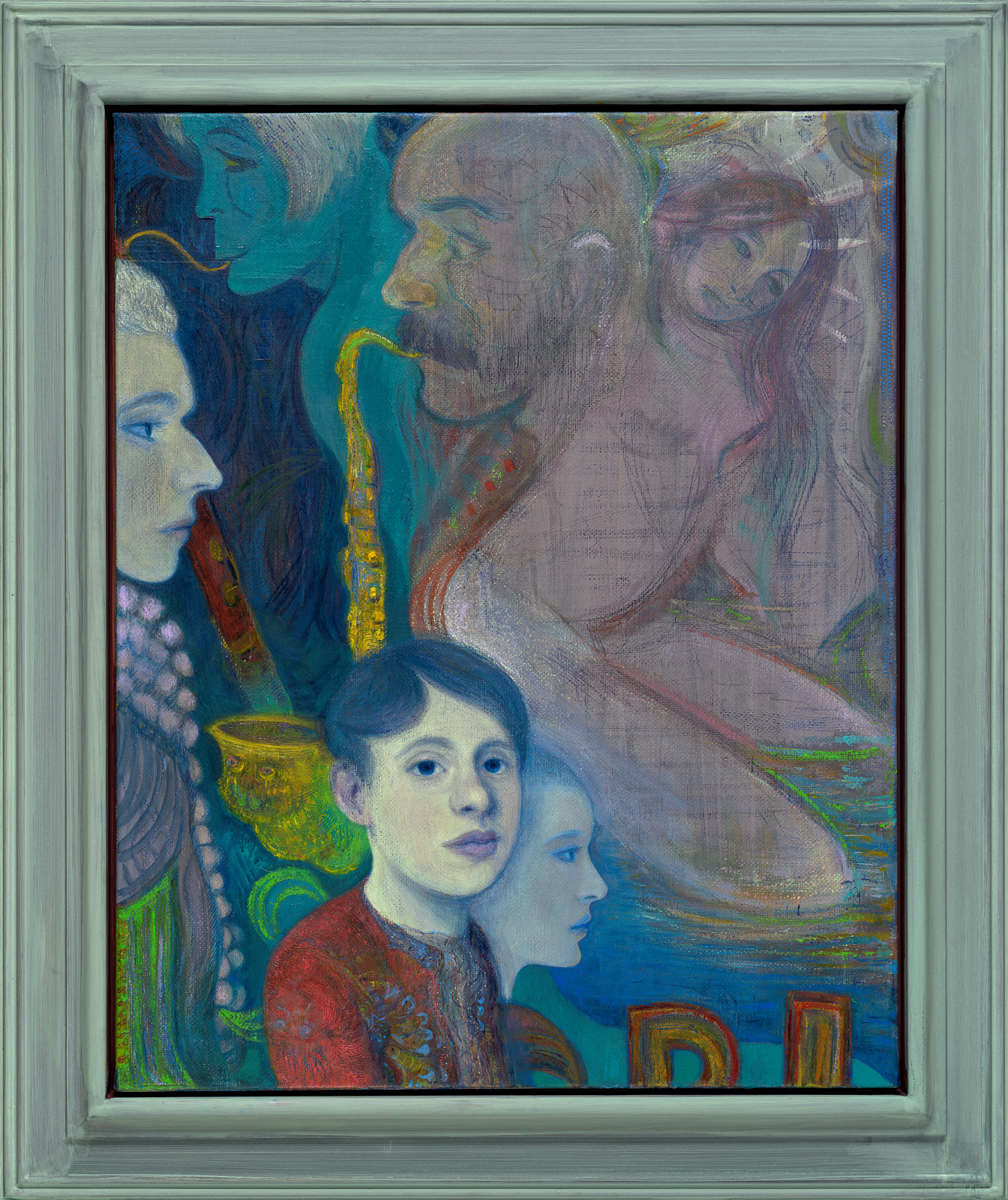

Steven Shearer. Young Symbolist, 2013. Acrylic and oil on canvas; artist’s frame. Image: 30 x 24 inches; Frame: 37 1⁄4 x 31 1⁄4 inches. Collection of Allan Switzer & Sandy Hazan. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

He is now essentially dedicated to paint. Impasto and sgraffito are utilized to realize dream world surfaces. Complex foreshortening and experiments in renaissance perspective create surprising depths, an illusionary field for his dandy personas. Named as Fauves and Fobs, he harnesses a beastly use of vivid color for their imagatoriums. Increasingly, the work pictures the figures’ world, moments of art deco decadence filling the air with successional experiences. Shearer is reaching back through early modernist material to find like-minded renegades in artistic pasts. The Fauves (2008-2009), Young Symbolist (2013), The Orientalist and Apprentice (2014), Chiseller’s Cabinet (2014) and Sculpture and Satyr (2016), could easily be called masterworks. This connoisseurship is claimed not just for the spectacular effects he achieves, but is grounded in his conceptual intent of creating work that answers to our accumulated history.

Through the final galleries of the exhibition, Shearer leads us back to his beginnings with some of the earliest works in the show. Silk-screens of seemingly deviant children, and collages of found photos collaged on searing abstract grounds bring us back to were we started: the youthful influences of suburban culture. Here we also encounter his image archive, published in encyclopedic volumes, available for perusing by the fire. Through the conscious articulation of the gallery as a place of study, Shearer continues to foreground the inspirational model of his painter/protagonist, and the historical role of the defiantly expressive commentator.

Installation view, Steven Shearer at The Brant Foundation. © Steven Shearer. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.