Charles Nkosi. Soweto at dawn, 1979. Watercolor and ink; 42 x 44 cm. Fort Hare University De Beers Collection, taken from De Jager, E.J. 1992. Images of Man: Contemporary South African Black Art and artists, University of Fort Hare Press: Alice, pg 184. © Charles Nkosi.

Sokhaya Charles Nkosi (b. 1949) represents institutional memory and knowledge; he is as much a historical figure as the city depicted in his watercolor-and-ink scene, Soweto at Dawn (1979), a center of Black creative arts in South Africa. Born in KwaMashu, a township north of Durban in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, Nkosi began to formally study art in 1974 at the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre, part of a large cohort of Black creative practitioners who graduated from this missionary school following their exclusion from South African universities during the apartheid era.

Like many other Black artists at the time, Nkosi was compelled to make art in response to the conditions of his people. While many of his contemporaries were leaving the country, he chose to stay. This characteristic resonates throughout his work: a patient display of those who stayed. From 1986, Nkosi has taught at the African Institute of Art (AIA) at the Funda Centre (now Funda Community College) in Soweto. Since then, the school has gone through various phases that are in many ways reflected in the symbolism of Nkosi’s work and illustrated through his stylistic approach. Like many Black contemporary artists, he began with printmaking, specifically cut-linoleum prints.

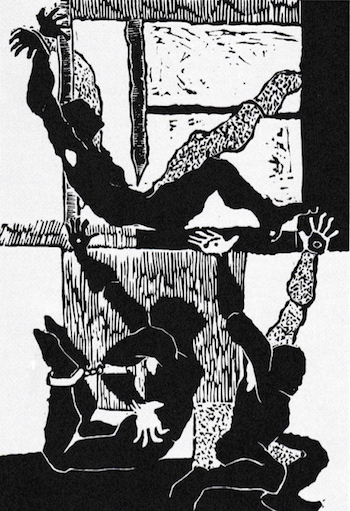

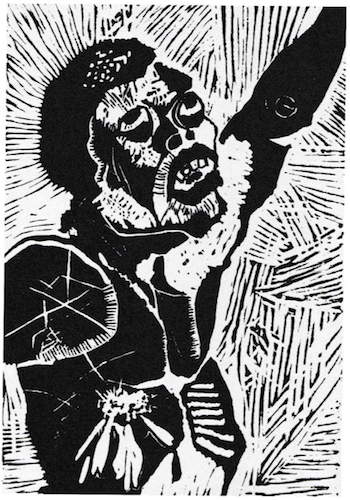

One of his most significant series from this period, Crucifixion (1976), resonates with protest art but more deeply denotes the agony of oppressed Blacks. In one image from the series, The Pain of the Cross II (1976), a physically constrained Black body is before an alluring White presence, one that seems to mimic and infect it. The upper part of the image shows a helpless figure with a pencil piercing through its abdomen and its arms tied to a pole. The bottom-left figure is in a contortionist pose, with a chain tying one arm to both feet. This figure is preceded by one with outstretched arms, a gesture that appears to be breaking its chains. The image Submission to Death (1976) depicts a Black man in torment; his oversized eyes look despairingly to the heavens, a characteristic motif in a homogenized category of work by Black artists, known as “township art.” While Nkosi’s work is indeed art made from the township and reflects the township condition, the work is centered on Black theology, an ideology that intertwined religion, Black existentialism, and the emergence of Black consciousness.

The narrow reading of Nkosi’s work as an example of “township art” indicates the effects of such classification by White art historians in South Africa. It results from the inadequate intellectual rigor in writing about artworks by Black artists that portray Black subjects in powerful ways. Nkosi’s repertoire challenges this approach in a number of ways, including his use of medium, terms of reference, and modes of artistic practice. While his recent works have become more abstract, his work retains its empathetic authenticity, remaining true to its material and its reference to his immediate environment. The gentle patches of colour in Nkosi’s collage The Abating of the Storm (2001) are as much about the availability of certain materials as about the innovative use of color as a way of seeing. This is important, given that a township is usually associated with neither color nor innovation, and so the work demands a different reading of place, one encapsulated by historical epoch. The work of Nkosi could be best described as “healing time scripts,” in that it is not only a record of time but also, more importantly, a depiction of a liberated era in Black expressive modes. Equally vivid is Nkosi’s encyclopedic memory of this profound moment, when Black South African artists were expressively inscribing their creative claim in time.

Charles Nkosi. The Abating of the Storm, 2001. Collage: magazine paper and fabric on canvas; 1.64 x 2.04 m. © Charles Nkosi.