Karyn Olivier. The Battle Is Joined, 2017. Acrylic mirror, wood, screws, and adhesive. Installation view: Vernon Park, Philadelphia. Photo: Steve Weinik for Mural Arts Philadelphia.

Monument Lab: A Public Art and History Project began five years ago as a conversation between Paul Farber and me. I had arrived in Philadelphia from Canada, and Paul had returned after completing his PhD in Michigan. We both had new positions at the University of Pennsylvania, where we taught classes on public space—he in urban studies and I in fine arts. During our first encounter, we discovered that we had been asking parallel diagnostic questions relating to the complex narratives of Philadelphia’s memorial landscape.

We mused about organizing an exhibition for understanding the mechanisms of memorialization, particularly by questioning the status of the monument and how we might challenge a monument’s canonical character. We were also interested in issues of embodiment that are inherent to the discernible ambivalence that is part of any construction of symbolic unity: the negated or unacknowledged histories that have been evacuated from the monument and yet remain palpable as an absence.

The extant memorial landscape of Philadelphia is identified with the dominant citizen class. This is expressed by the nearly total absence of officially sanctioned statuary of African Americans and women anywhere in the city. Philadelphia unveiled the first public memorial to an African American in September 2017, a statue of the great nineteenth-century civil-rights advocate and educator, Octavius Catto. We noted that African Americans make up more than 40 percent of the city’s population, and the story of African American struggles and contributions are central to any appreciation of Philadelphia’s greatness. We noted that there are only two historical women represented as full figures within the immense inventory of Philadelphia statuary.

We also saw Monument Lab as an exercise in spatial production, in which the spaces of the city are opened to question. Monuments tend to render their sites incontestable, where different readings of space are not permitted and where it is assumed that one system of values is shared unequivocally by all. We wanted to make an exhibition about monuments that challenged these assumptions.

Hank Willis Thomas. All Power to All People, 2017. Aluminum and stainless steel. Installation view: City Hall/Thomas Paine Plaza, Philadelphia. Photo: Steve Weinik for Mural Arts Philadelphia.

Philadelphia is a vast metropolis, with more than a quarter of its 1.5 million inhabitants living in poverty. Given that poor areas of the city also suffer more acutely from poorly funded public schools, high crime rates, and familial fracturing, we erected Monument Lab containers—offering a busy schedule of activities—at many sites within and far beyond the center of the city, including Norris Square, Malcolm X Park, Marconi Plaza, Fairhill, Penn Treaty Park, and Vernon Park.

One role of Monument Lab was to prompt members of the public to identify with the flaneur, a figure who wishes to “rush into the crowd in search of a man unknown to him” and to throw “away the value and the privileges afforded by circumstance,” as Baudelaire wrote in The Painter of Modern Life (1863). We wanted Philadelphians to visit places within their city that they had never before visited, to experience their city through the lives of others.

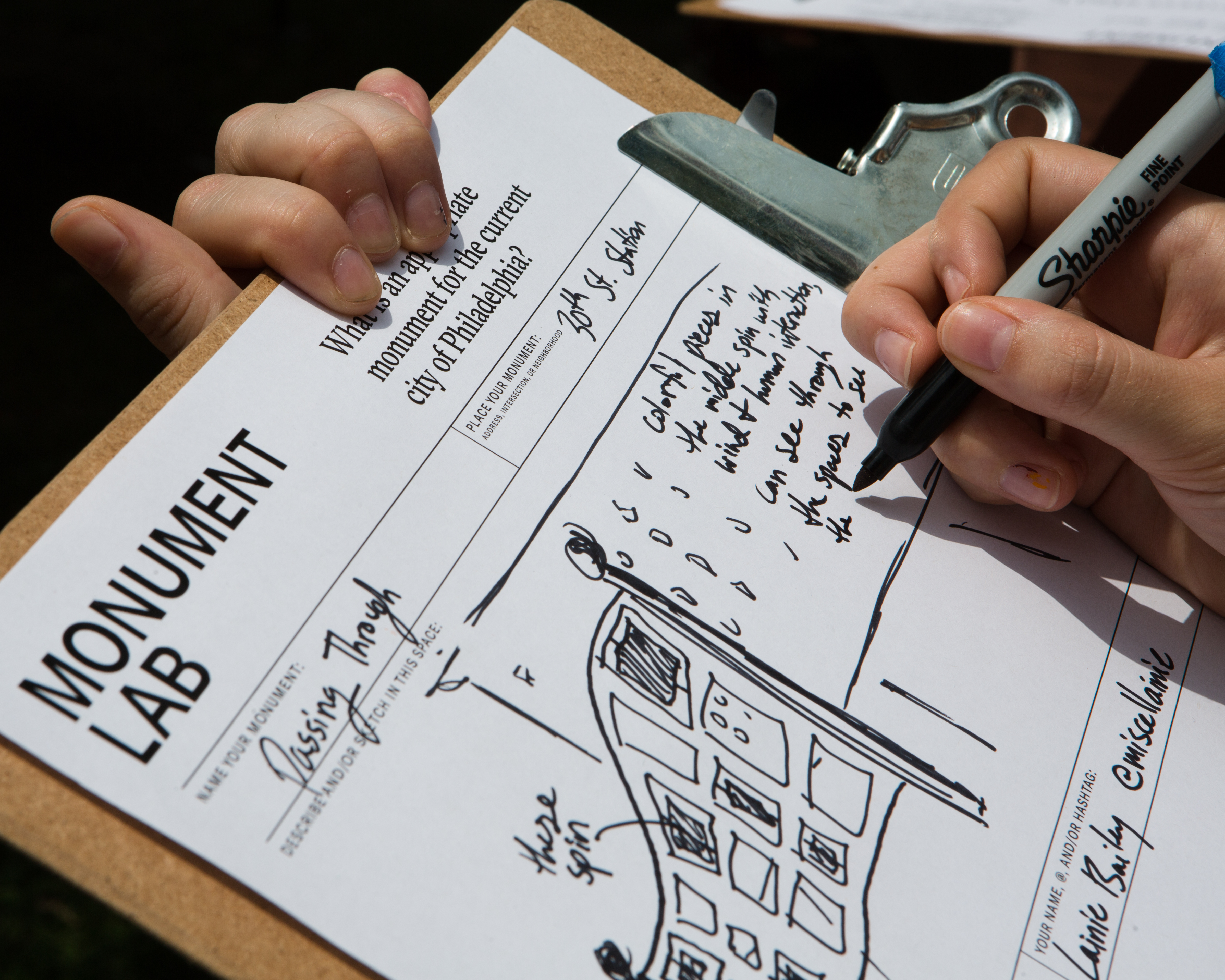

We were interested in the idea of public memory serving as future speculation. At the labs, members of the public were asked to respond to the following question: What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia? By asking what would be appropriate rather than ideal, we opened conceptual space for respondents to subjectively interpret the question according to whatever criteria they chose.

The depth of public memory surprised us. Many proposals dealt with the terrible state of Philadelphia’s public-school system. Others dealt with the city’s distinctive neighborhoods, some at the most immediate street level. There was a small but significant number of proposals calling for a memorial to the 1985 bombing of the compound of MOVE, a Black liberation group. The proposals revealed that Philadelphians are animated about the application of public art and public history to this city; if they feel their ideas and experiences are valued, they are willing to participate directly and contribute ideas in a process of creative speculation. Through this project, we were reminded how rarely the public is asked to think about what histories, places, and people are worth remembering and commemorating in official contexts.

Tyree Guyton. The Times, 2017. Wood, paint, and mixed media. Installation view: A Street and Indiana Avenue. Photo: Steve Weinik for Mural Arts Philadelphia.

As we learned, Philadelphians are distinctly aware of the impact of politics on debates about memory and advocacy, the importance and significance of a broad range of monumental sites, and the city’s historical sites and perspectives. It became clear that the people of Philadelphia were already thinking about our central question—or at least some form of the idea of what the city is, what it was, and what it can be through a process of participation and monumental production.

Philadelphia is the home of the Liberty Bell; we saw the crack in the bell as a fissure that haunts us, a wound that refuses to heal. For all the glorious language that makes up the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, the United States of America is a place founded on the wounded bodies of Others—the indigenous, Black, indentured, gay, impoverished, and many more.

Monument Lab operates between digital humanities and civic engagement, offering key ideas and methods for Philadelphia and other cities. Seeing a shift in the public understanding of monumentality, we created a welcoming site-specific research method and the conditions for a more nuanced discussion about public art, public history, and social practice.

Monument Lab was a public art and history project led by curators Paul M. Farber and Ken Lum, and produced with Mural Arts Philadelphia. Between September 16 and November 19, 2017, Monument Lab invited Philadelphians and visitors to join a citywide conversation about history, memory, and our collective future.