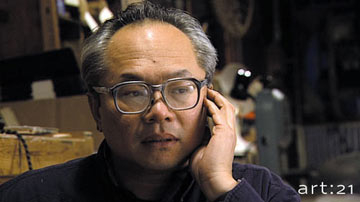

The following interview with Season 1 artist Mel Chin took place in late February 2008 at Art21’s offices. Part 2 will be published on Monday. Stay tuned for further information on Mel Chin’s presentations at next week’s National Art Education Conference in New Orleans, LA.

ART21: Could you explain how the Fundred Dollar Bill project came about, what it is, and what “Fundred” means?

MEL CHIN: I was in Houston, and I ran into a good friend, Rick Lowe, who said, ‚Äúwe‚Äôre going to New Orleans to do something.” It was six months after Hurricane Katrina. He was talking about the New Orleans Biennial. And I remember telling him, “that‚Äôd be great.” But half the population was gone. I was thinking about art from a community point of view, as Rick does. We had an interesting conversation about it. I said to Rick, “let‚Äôs go.” Rick and I were part of discussions with Transforma Projects, arts people from all over the country that met in New Orleans to come up with a response to the tragedy. So we toured and we looked, but we mostly conceptualized about what we could do.

So the project really came about this way. I was in the Ninth Ward, and I was overwhelmed. There was no more water, but I was flooded with an emotional and psychological response that was uncommon for me as a creative person. I felt hopeless, because I felt there was nothing I could do.

Then, you had the debris and the evidence and the remains of who knows what? I don’t know. And no one else knew, either. And so I left. I remember going to the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence to receive an honorary degree. I didn’t want to go, because I felt compelled by the tragedy of this magnitude to move into really dramatic action, but I didn’t know what I could possibly accomplish. Whatever it was, it had to be meaningful.

Maybe that detachment was important; I was meeting people who were going down there to work and clean. That was wonderful, but I didn’t know if that kind of response was right for me. And that detachment helped me to see it another way. It made me go back again and again and research and find people outside the arts community.

When I was working on Revival Field in Minnesota in 1991, I met an important scientist named Howard Mielke, who is now at Tulane/Xavier Center for Bio-Environmental Research in New Orleans. He has been studying the soils of New Orleans for twenty-five or thirty years. He’s an expert on the effects of lead and testified about lead to Congress in the 1980s. I called him to ask about how bad the lead content of the soil in New Orleans was post-Katrina.

Howard had accomplished a project called Recover New Orleans. He tested and treated twenty-five properties in one of the city’s most dangerous zones, with a high murder rate. It also had the highest lead levels. I said, “Howard, we have to do something. How much will it cost to reclaim the soil in New Orleans?” He asked, “all 86,000 properties?” He said that would cost about 250 million dollars. To which I replied, “I can‚Äôt raise that much, because I‚Äôm an artist, but I know we can make that much.” I didn‚Äôt say it would be real money or anything. So I promised him that. It would take a big landscape effort, a landscape art effort.

And that’s how this project was born. Its code name is Paydirt. Paydirt encompasses the overall operation, which raises awareness and money and then executes the transformation of the 86,000 properties. The Fundred Dollar Bill Project supports Paydirt.

I describe the Paydirt operation as having two sides, one covert and one overt, all still one project. Fundred is covert only for the time it needs to be, to gather the expression, the voices of kids. The other side, the landscape side is overtly trying to be actively engaged in transformation, the physical and scientific and verifiable method to transform a city in need.

ART21: So a kind of before and after?

MC: Yes, it’s an evolution. We have a two-part process, a process to make all this money, art money, which I think is equally valuable as real money.

ART21: Now can you explain more specifically the Fundred aspect itself?

MC: Fundred is an operation conducted by three million kids. I am the paper delivery guy, that‚Äôs how I look at it. I will deliver their art [to Congress]. And why their art? Why am I working with children? Because children are the most at risk. They‚Äôre the ones most affected by the degraded conditions in the soil, in their air, in their homes. They’re the most at risk yet they have no vote, they have no rights, they don‚Äôt have a voice. So the voice that we could find is the art they make. That voice is powerful. Also, looking at the map of the diaspora of Katrina [victims], I looked at all the cities where New Orleanians ended up after Katrina, [as] in Salt Lake City and Portland [Oregon]. I wondered how we could reach children evicted from their homes and make their voices count. We have to collect their thoughts. It was important to keep it elegant and simple, to create a project that was dependent on their creative input and then deliver it intact. The main thing a kid needs to know is if s/he does one drawing, our team, the Fundred team, will deliver. I will deliver. I have to deliver, or I disrespect their art.

So it came to me that Fundred would be fundamental to raising a voice strong enough to be heard‚Äîtheir voices, not mine. My voice was just saying, “look, I‚Äôm working on a solution for this city. With Paydirt we will have developed a cohesive methodology of how to cure one problem that is pervasive. At the same time, it would have been done because of the voices of three million kids.

ART21: How are those voices manifested?

MC: They’re manifested through these drawings, all 6,608 pounds of them. That’s one gram apiece, calculating paper at 1/4000th of an inch thick: the size of a dollar.

ART21: Ok, so explain what happens. You contact a school…

MC: Okay, this is the step. You just go to www.fundred.org, and you put in the password: “paydirt” and it explains the project briefly. Not everything, but enough to understand. And then you can download two PDFs: the lesson plan and Fundred worksheet. The worksheet has annotated all of the symbols and components of a real hundred dollar bill. The actual template has all of the specifics removed, so that kids can personalize their bills using their own ideas and symbolism. The lesson plan teaches the teacher how to run the project.

The worksheet needs to be printed on both sides in color, because it was calibrated to have the look and feel and color of money; the drawing pattern is similar. It’s been cleared, I believe, by at least one Secret Service agent. The artists follow the template. They can do a portrait of themselves, their dog, their cat, or pet, their mother, their father, their hero. They have the ability to express whatever they want. On the reverse side they’re asked to put a slogan and a portrait of their home, because it’s about their home too. And that’s their obligation. All kids look at money, they know about money, but this project teaches them about not only its value but also some of the more arcane aspects of what’s on our money, symbols and things.

It takes 25 minutes at the maximum, more likely 20 minutes for a child to do the drawing with a black ballpoint pen. The requirement is only one bill or one drawing per child or adult or grandfather. There is no age range, but we prefer children, simply because they are the ones most affected by the lead.

ART21: Why with a black ballpoint pen?

MC: It was a standardization procedure to make it easier for the teacher. But there’s no restriction. If they want to use color, whatever, we’re not opposed to anything. Some kids like to start and do it in pencil to be careful and then shade it in with the pen.

The most important thing I tell the teachers is that they must ask the students after they‚Äôve finished the drawing, ‘will they donate this art?’ I don‚Äôt want to use their art if they want to keep it; they can keep it for themselves if they want to. They draw and finish the worksheet, designating a “scissor person.” You‚Äôve got to watch out for that. I‚Äôve learned that it’s important to find who‚Äôs going to cut the bills. The kids for some reason want to do the cutting. Anyway, the bills are cut on the dotted line and the teacher collects that class‚Äôs work.

So the teacher collects the bills from the students and consults the lesson plan for instructions on cutting out the bundle wrap. You use your glue stick or tape and you bundle up a hundred of the bills. The teacher signs the bundles and provides the name of the school so they’re identified. And then the teacher has to go back to the website and find where the Collection Centers are and send their Fundred bills to the nearest one. We have 46 Collection Centers in 29 states now. The vault for each of these schools can be a banker’s box. And it has to be watched by the kids or whoever is responsible, because it is precious. Any school can collect.

So the Fundreds are in holding for the moment, until it’s time for an armored car to come and collect it. The collection will be made by a famous armored car that was used in the Darlington NASCAR million-dollar giveaway back in the 1980s. They actually threw fake money out of the back of this armored car (which we procured through means I‚Äôm not at liberty to discuss). I just got word the paint job is done and the motor runs. We have put a new motor in that runs on two tanks of straight vegetable oil (SVO). It‚Äôs an SVO vehicle. Why? Because we want to have a green situation for this greenback collection, but also, we felt that on top of going to each school, it would be great if it could be refueled at the school cafeteria as opposed to your normal channels of diesel operations.

It’s possible that many schools in one city will collect this money‚Äîthis art, I shouldn‚Äôt say money. It‚Äôs better than money; it‚Äôs art. The armored car will go in relay fashion. It will stop at the school and fill up. At least a month before the armored car begins its journey, every school that we‚Äôre picking up from will be notified to get the oil from local restaurants. As long as it‚Äôs vegetable oil, it‚Äôs fine. The more it’s been used, the better. And you just put it in a five-gallon container and let it sit. If you let it sit, it filters down, it prepares us for our fill-up. We don‚Äôt need biodiesel or dangerous chemicals, just the oil. We‚Äôre going to try to have performance teams or volunteers serve as security guards.

ART21: So this is like a Brinks truck?

MC: It is a Brinks truck. It is a classic 1977–79 GMC model. It’s got the classic look, the bulletproof glass, and everything else. And we have a logo, which I will not reveal because we want to keep it covert. It’s an operation that three million kids are part of, covert only in the sense that we want to maximize its public-relations value. My feeling about covert operations done in the name of art is that they are there to heal and establish presence and not undermine and control. It’s about expanding expressive possibilities. So I wouldn’t be worried about this term; just keep it quiet so you can make it effective, is how I see it.

ART21: Where is the truck now?

MC: Right now it is at Chuck Randolph‚Äôs Paint and Body Shop, somewhere in North Carolina. It‚Äôs ready. I‚Äôm going back there to look at the special paint. We‚Äôre getting the signs made and getting it ready. And we want to bring it to the NAEA’s national convention in New Orleans, next week. We‚Äôre doing this as a bonus for them.

ART21: This is a dramatic act in New Orleans?

MC: Oh, yes, we‚Äôre going to orchestrate it. We‚Äôll do everything at the Super Session (Friday, March 28 from 1:00-2:50pm in the Morial Convention Center’s La Louisiane ballroom). The teachers will draw Fundred bills. Then we‚Äôll go outside for something special.

ART21: How many schools are involved now in how many states?

MC: We have almost 50 schools in 29 states. Streamwood High School, outside of Chicago, reported about 4,000 bills collected thus far. It‚Äôs a major school, a pickup site. We’re excited about this. The national convention is very important, to galvanize anybody else that‚Äôs out there.

ART21: How many do you think you have total now?

MC: I don’t know. The site is estimating five million Fundred dollars, but I don’t know. It’s been spreading only through the website and word of mouth, so I don’t expect big numbers the first accounting.

ART21: When did it start?

MC: About a year ago.

ART21: That’s when you started talking about it.

MC: I started letting people know about it and sending a description, just on my own through a PDF that was not even formed, corrected, or anything. I just started sending them out from my office. We created the website five or six months ago.

ART21: Talk about the other aspects of it, because we have a little bit of video from the George Jackson Academy. What is striking is that the teachers used the project as an opportunity to discuss many issues, and the children are serious and thoughtful in discussing them, in addition to doing their artwork. It would be interesting if you’d talk a little bit about the surrounding things that you thought might happen in the classroom.

MC: Yes, I think a teacher who is talking about Fundred needs to calibrate the discussion to the age of the child. But every child is already experiencing problems related to pollution. They’re conscious and if they understand good and bad, then they know the world is not all content. I think that the way I structured the worksheet, you could talk about what money is about. You could talk about what art is about, what printing is about. And you can talk about what donation is about, what you’re giving for.

Teach and talk about how art can take many forms; it can be your expression, and it can be a collection. And that‚Äôs what I think about. That‚Äôs how I see it, all these bills being one huge artwork. It‚Äôs not a Mel Chin piece. I would immediately tell the teachers who refer to it as my project, “No, it‚Äôs not my project. It‚Äôs not mine.” The project means nothing without a child‚Äôs contribution. We told the security [guards] to treat this just like the real thing, because I truly believe we will be exchanging the artwork for services or whatever, when we deliver it.

to be continued…

Pingback: Off Center » Centerpoints 9.4