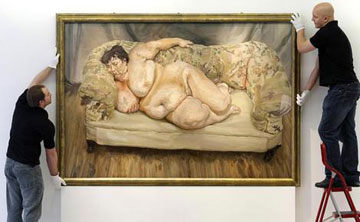

Roman Abramovich, the partially-bearded Russian owner of Chelsea Football Club (AKA ‘Chelski’), and 16th-richest person in the world (according to Forbes), was this week reportedly the purchaser of two paintings by significant British painters. Lucian Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping and Francis Bacon’s Triptych (1976) sold at auction in New York for a collective total of around $120 million.

Meanwhile, it emerged that the model for Freud’s vast canvas of a overweight woman reclining on a bulging couch, Sue Tilley, was paid about £20 ($38) a day to pose. While it’s tempting (and very high school maths exam) to work out how long she’d have to pose to be able to afford the painting she was posing for, it’s perhaps more interesting to consider the always-baffling disparity between an object and its value.

Freud’s painterly insistence on the quiddity of his subject – the lunar impasto of paint on the bulge of Tilley’s stomach, the layers of tone gradually ‘becoming’ flesh – is predicated on the idea that paintings are in their essence traces of elapsing time, time that (here) directly corresponds to a financial transaction. The thought that each brushstroke translates into a before-and-after set of specific values is weirdly giddying, like comparing the price on the menu and the price on the bill.