EXCLUSIVE: Josiah McElheny discusses his film Conceptual Drawings for a Chandelier, 1965 (2005), shot at The Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Josiah McElheny creates finely crafted, handmade glass objects that he combines with photographs, text, and museological displays to evoke notions of meaning and memory. McElheny’s work takes as its subject the history of Modernism and the impact it has made on society, aesthetics, and contemporary thought.

Josiah McElheny is featured in the Season 3 (2005) episode Memory of the Art:21—Art in the Twenty-First Century television series on PBS.

ART21: Could you talk about the impetus for your film Conceptual Drawings for a Chandelier, 1965? You’re known primarily as a sculptor, so why did you decide to make a film?

MCELHENY: Well, my first idea wasn’t a film. Instead I wondered wouldn’t it be really interesting to remake one of those, not as a chandelier, but as a sculpture so you could really get close to it?

What was interesting about being up high by the ceiling in the cheap seats at The Metropolitan Opera was you were a lot closer than most people would be. So you could kind of look at them, but they were still too far away to really look at. They’re intended to be examined from far away. And in fact, if you look at them up close — which I’ve now done from the attic — they’re actually quite crude in a certain sense. They’re not intended to be looked at up close.

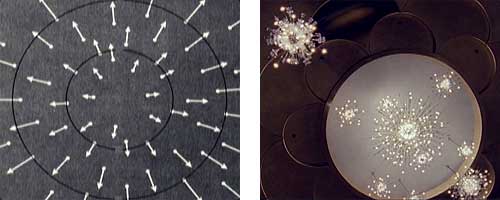

My notion was: what if you made this and put it in the space of your body so you could walk right up to it? And then what if we made them where it actually were a scientifically correct model of the Big Bang? So what if there were some trueness to my flash idea about it?

I was invited to do a project with the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University that came with only one stipulation: that I would do a project that I couldn’t achieve on my own, and that I would use not just the budget but the resources of the university in some way. And they said, “Do you have an idea like that?” And I said, “Yes…” (LAUGHS) So they connected me with David Weinberg who is an important cosmologist or expert in the history of the universe. And we worked together for 18 months on creating a “model” of the history of the universe. And he was very skeptical at first because, for many conceptual reasons, building a model of the history of the universe or of the Big Bang is sort of impossible for one simple reason: because the universe may be infinite. So how do you make a model of something that’s infinite in any significant way shows that?

In the end my notion of wanting it to look like these chandeliers turned out to be crazy enough that it actually changed our thinking about it because as we talked we realized that while you can’t make a model of the space of the Big Bang, or the space of the history of the universe, but you could make a model of the history of time of the universe.

So in these sculptures time is represented conceptually by the length of every rod that extends out from the center of the sphere. And then at the end there’s a cluster of objects that depict what kinds of things are happening in the universe in terms of the clustering of galaxies at that moment. It’s a kind of pop image of complexity. It looks like a ’60s object. It has light but it doesn’t give off enough light to actually be a chandelier. It also has this very unusual sense of it being a manufactured object but having all this unique complexity because normally manufactured objects are the result of repeated actions, of repeated parts. But in these sculptures everything is unique: every length, every hole, every placement of everything is uniquely placed and based on the science. It has this level of diversity in terms of its aesthetics that’s unusual and is part of the main message of it as this image of an explosion. Then the more you examine it, you realize that there’s some kind of complex reasoning behind it.

ART21: Did you know much about the original chandeliers before seeing them at The Metropolitan Opera?

MCELHENY: As part of the research for the project I went to the Czech Republic and Vienna and met with the people who made the chandeliers at the Met. And it turned out that my intuition was not so surprising in that’s actually what happened. Wallace K. Harrison, the architect who designed the Metropolitan Opera, commissioned them in 1965 to do this. 1965 happens to be the year that the first physical evidence of the Big Bang was discovered. It was front-page news on every paper in the world. It proved Einstein wrong, and in my opinion, is a significant event in the history of modernism.

That’s why the first chandelier sculpture is called An End to Modernity (2005). One of the most basic idea of modernism is the notion that there is a sense of a narrative and of progress to history. And basically the Big Bang theory says nothing doing: there is no center to the universe and not even one history of the universe can be told. You can tell the history of the universe from any place, or any time, or any point of view and it is equally as valid. This is in some sense a corollary description of what we might call Postmodernism.

I don’t know for sure whether it was specifically the evidence of the Big Bang that influenced Wallace K. Harrison, but I think it’s not farfetched to say. And while Harrison had already commissioned J. & L. Lobmeyer, the company, to make these chandeliers, during the process he gave them a book about astrophysics and galaxies and said that he wanted them to be based on these ideas. So it seems quite likely that that decision may very well have been caused by this huge news. So what I did for the film was is try to pretend that this connection was even tighter.

ART21: Could you talk about the process of making the film? Making films are generally very collaborative processes, and making glass is as well…

MCELHENY: I knew that I wanted to make the film on film. And, I hope at some point to make another version of it that will actually be shown on projected film. Right now it’s being shown on video, but it still has the quality of film. I had no experience with making films, although I’ve done a lot of editing of books, so I have experience in sequencing images. I found a documentary cinematographer to work with who was used to working in difficult situations, which was essential because the permission to film within this famous edifice was extremely difficult to obtain. Our time was very compressed as well, so we had to work quickly and on the fly. The process was very simple. We took, I don’t know, 90 minutes of film of the chandeliers that got edited down to maybe two minutes.

I learned a lot about the kinds of effects and techniques that we could use for filming from our cinematographer, Adolfo Doring. Essentially, it was the same kind of process as working with an editor. Normally, when I’m making the parts of my sculptures or installations that are out of glass I will collaborate with a mold maker, but I’m still generally figuring out everything myself. Often times it is some new kind of process or a new twist on process so, I have to figure that part out on my own. This project didn’t turn out to be so different because I still had experts helping me through the learning process. Then, once we got to the point where the vocabulary was established, I could play with things until they coalesced into something that fit with my original idea.

ART21: Could you talk about the difference between having your own work photographed and filmed, and then filming these other objects that you didn’t make? Do you think that you’re applying a similar sort of rationale?

MCELHENY: Filming at the Met was not only about these objects (the chandeliers), but also about the building itself because the chandeliers are part of the architecture. So, even though we really only focused on these objects, the space played a large role in the film. The theater and the grandness of the space is very much a part of the film and the experience we were trying to impart. We tried not to document per se, rather to provide another way of looking at the chandeliers that one would never experience in person.

So, in that sense it was very different than photographing my own work. I am interested in how one’s artwork is communicated through language, and I’m very interested in how to present it whether I’m giving a lecture or writing something that leaves things open-ended. Photographs have the same open-ended possibility for interpretation. One can make an interesting and dynamic photograph, but it may have nothing to do with what it would actually be like to experience what is portrayed. It is tricky because obviously one of the great things about art is that unlike many other endeavors people are engaging in the world art must be experienced in person. It has to be experienced on a physical level. And, I think that right now capitalism proposes the exact opposite: everything can be translated into a repeatable, copy-able piece of information. I think it’s very important to resist the notion that everything is reduce-able to that. Of course there are some artworks that can actually engage in that question itself, but most artwork inherently doesn’t and can’t.

The process of how a work is investigated is one of the things that I’m most interested in. I’m especially interested in the idea of what kind of information you take in the first instant. And also, how that affects everything else that you might think about later. And, how that either draws you in, or repulses you, or confuses you, or enlightens you, or a number of other things.

What I try to do when I’m making my work is design something that entices by giving a lot of information right away. It’s a dangerous way of working. If artwork offers a mirror of the complexity of the world, it can be more than just enticing, it can also be horrific, or terrifying, or confusing. I think a lot of artists use this kind of opposite strategy so that the initial moment offers a kind of visual interest coupled with some sense of repulsion, or of fear, or confusion. In my experience, something may be off-putting at first, but the more time you spend with it, the more it becomes the opposite. And the reaction can be a kind of empathy or a connection. It’s something I think about a lot.

Once works of art leave your hands they have a life of their own. So, I think it’s very important if you can to try to help the artwork be as open-ended as possible. Some artists don’t want to have anything to do with aspects of being an artist other than just making the thing, and that’s fine, but I think it’s really important to continue to promote the idea that art is a completely contingent exercise. Art must constantly be re-examined, questioned, looked at, and thought about. Essentially, this is true freedom: the freedom for individuals to remake the world in their mind, in their own image, and to do that by being confronted or encountering other ways of looking at the world. As Dave Hickey has said: art can be a civilizing force because it can expand our ideas and reduce our fear of our anxiety…it can increase our ability to move past our initial anxiety about things that are unfamiliar and challenge us to think differently.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

VIDEO | Producer: Wesley Miller & Nick Ravich. Camera & Sound: Nick Ravich. Editor: Jenny Chiurco. Artwork courtesy: Josiah McElheny. Thanks: The Museum of Modern Art, New York.