The relationship between fine art and pop music is characterised most often by a specific historical period in Europe and America, the mid-sixties, which is probably the closest point there has been or will be between the two disciplines. Like its relationship with cinema, art was never completely comfortable with pop music, all smiles in public but laughing behind its back when the coast was clear. In reality, Warhol’s peelable banana on the first Velvet Underground record had little or no relation, aesthetically, to the music it contained. Double Elvis has more to do with Barnett Newman than The King. Maybe that’s partly to do with the unbridgeable gap between them: a still point of time versus three unfolding minutes; in market terms, coy flirtation (at most) versus out-and-out capitulation. In pop music, the commercial imperative has produced some of the greatest masterpieces of twentieth-century culture; in art, selling out retains its weird taboo. I imagine Rirkrit Tiravanija lost a few fans by designing a Gap t-shirt; pop music is so bound into commercialism that no-one bats an eye when Keith Richards poses for Louis Vuitton.

It’s usually implied, as befits Western cultural hierarchy, that art borrows from popular culture — that it redeems it, even — as part of a post-Duchampian mindset that lends the artist a kind of alchemical magic touch. Base matter becomes gold. But it’s when pop music returns the favour, taking art as its inspiration, that stranger and more interesting things happen. The Modern Lovers’ Pablo Picasso, David Bowie’s Andy Warhol, Lou Reed and John Cale’s Songs for Drella album — it’s often when art is transmitted by other means that you end up returning to it, refreshed. Who wouldn’t love Van Gogh after hearing Jonathan Richman’s Vincent Van Gogh: “He loved, he loved life so bad/His paintings had twice the colour other paintings had”?

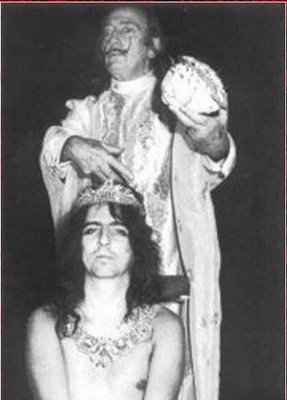

Picture: Salvador Dali (standing) and Alice Cooper (sitting)