Our exposure to the photographic image on a professional as well as a private level has steadily increased since the first photograph saw the light of day in 1839. The photographic medium has become a natural part of our everyday life and has changed our whole way of seeing and perceiving. We have grown accustomed to photography so that our decoding of it happens unconsciously. Nevertheless, there are still some photographies that for some reason talk to us and make us stop in order to more closely examine what it is in the particular photograph that affects us, thereby separating it from the enormous amount of graphic material we are exposed to daily.

Photography appears to be a fundamental form of communication, yet it still seems difficult to define. The perception and the theorization of photography and its context is placed in a paradoxical field and for a long time, the discussion was based on whether photography could be defined as art, rather than exploring the core of its meaning. However, if you’re trying to catalogue the theoretical intersection surrounding photography, there are two main directions, namely the formalist essentialism and the discourse of analytic contextualism. While Walter Benjamin is an proponent of the first and John Tagg for the latter, Roland Barthes, although predominantly essentialist, performs between these two theoretic polarities. In Camera Lucida (1980), Barthes develops themes such as proximity and distance, the relationship between photography and theatre, history and death. He identifies the exchange of meaning between the photography and the viewer and mentions two elements, which he thinks are present in a successful photography, studium and punctum. While studium is the reflection of the relationship between the obvious symbolic meanings of a photograph, punctum, is the personally touching detail within it, which establishes a direct relationship with the photographed object or person.

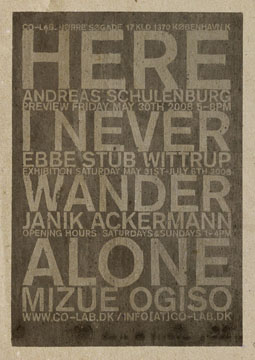

With this in mind, I was impressed as well as surprised a few days ago when I attended the opening of the exhibition Here I never wander alone at the Co-Lab gallery in Copenhagen.

The particular piece that impressed me, Wandern by debuting Swiss artist, Janik Ackermann, is a photographic experiment where the emotional and the aesthetic accompany a visual fantasy. Ackermann has created a mountainous scenery behind a pane of glass installed in the wall. Through the glass, you can gaze at a three-dimensional, sculptural landscape built in the technique and tradition of model building, sending references back in time. The mountain landscape is presented as a detailed and realistic picture, and regardless of the three-dimensionality, the piece does in fact resemble photography. Unlike the photograph, though, Wandern is not technically reproducible–it has maintained the here and now, carries traces of the past within—yet I still see it as some kind of reproduction. It restores an image or a feeling that lies deep within, which is emphasized by the artist’s companion text to the piece, where he mentions that he in Wandern has recollected a childhood experience. Wandern is observed with a certain distance and is shrouded by an aura, thus remaining unique. It is a manifestation of the past, the memory and the personal, and to me it contains all of Barthes’ three photographic components; studium, punctum, and noem: pure representation, which points at the passage of time and shows what once was.

Janik Ackermann writes: “The work Wandern discusses the loss of a childlike carelessness and the regret I still feel about it. It is an approach to reproducing a memory as detailed as possible, using the technique of model building. In my point of view, model building generally tries to regain carelessness of some sort. A model is a desperate attempt to replicate our world in every detail. Only in most cases, the model builders leave out the sorrows and distress of everyday life, not to mention the cruelty and terror that is also a part of this world. In this sense a model creates its own reality while simultaneously emphasizing the utopia of it. My memory is certainly an equally utopian thing, a mixture of several memories and to some extent of wishes, imaginations and dreams. In spite of all that, the memory seems to have its own reality.”

Here I never wander alone will be on view at Co-Lab until July 6th.